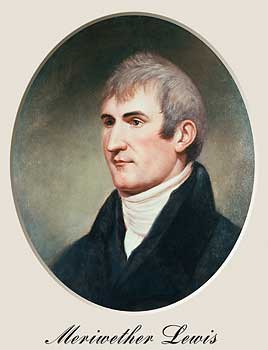

When President Thomas Jefferson considered a potential leader for an expedition across the continent to the Pacific Coast in 1803, he looked no farther than his personal secretary, Meriwether Lewis. "It was impossible to find a character," wrote Jefferson, "who to a compleat science in botany, natural history, mineralogy & astronomy, joined the firmness of constitution & character, prudence, habits adapted to the woods, & a familiarity with the Indian manners & character, requisite for this undertaking. All the latter qualifications Capt. Lewis has." Who was Meriwether Lewis, what events led him to the point of enjoying the President's complete confidence, and what happened to him after the famous expedition which bears his name?

The future explorer was born to William and Lucy Meriwether Lewis on August 18, 1774 on the family plantation "Locust Hill" in Albemarle County, Virginia. The Lewis family also had a daughter, Jane, who was born in 1770, and another son, Reuben, born in 1777. Young Meriwether and his siblings did not see much of their father, who actively fought the British during the Revolutionary War. The elder Lewis periodically visited while on leave, but after falling from a horse into a flooded river, he caught pneumonia and died. A short time later, Lucy married Capt. John Marks.

Meriwether Lewis spent much of his time as a youth in the outdoors, and developed an interest in plants, animals, and geology. When Lewis was eight or nine years old, his family moved to a colony on the Broad River in northeastern Georgia. In the four years he lived there he honed his wilderness skills and became proficient with a black powder rifle. He returned to Virginia at age 13 for formal schooling and to learn to administer the family plantation of nearly 2,000 acres, which was worked by 24 slaves.

Over the next few years Lewis was taught by a variety of schoolmasters and tutors, but his schooling came to an abrupt end in 1792 when his stepfather died, his mother moved back to Virginia, and at the age of 18 he began to actively manage Locust Hill. He spent two years on the plantation, where he grew tobacco, corn, and wheat. Life as a planter had its challenges and rewards, but Lewis was striving for other things. He enlisted as a private in the Virginia Volunteer Corps during the Whiskey Rebellion of 1794, telling his mother that he wanted "to support the glorious cause of liberty, and my country." During his service he saw a good deal of unfair treatment of enlisted men by officers, who sometimes didn’t provide the soldiers with proper clothing, equipment, and food.

Despite the drawbacks of military life, Lewis must have liked something about the army, for on May 1, 1795, he joined the regular U.S. Army at the rank of Ensign. His enlistment came at a time when the United States military was dwindling from 5,424 officers and men to a total strength of only 3,359. Lewis met many officers in this tiny army who made an impression upon him, few more so than a fellow Virginian named William Clark, who commanded the Chosen Rifle Company of elite rifleman-sharpshooters. After six months of serving in the military together, Clark resigned his commission because of family and health problems.

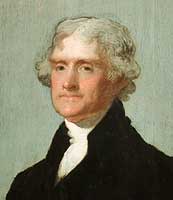

|

| Thomas Jefferson. |

During Lewis' service as the President's secretary, he learned about diplomacy, statesmanship, and national policy from a master politician. Meanwhile, Jefferson came to look upon Lewis as the finest candidate to lead a government-sponsored scientific and diplomatic expedition across the continent, an expedition Jefferson had proposed several times over the course of a ten-year period. The president knew Lewis’ strengths and weaknesses, and to groom the young man for the expedition had him tutored by the finest minds in the United States, including Dr. Benjamin Rush, a prominent Philadelphia physician, Dr. Benjamin Smith Barton, a professor and botanist, Dr. Caspar Wistar, the foremost authority on fossils of the time, and David Rittenhouse, America's most famous astronomer and mathematician. As the time approached for launching the expedition, Jefferson drafted a set of detailed instructions for Lewis which outlined the importance of the journey and Jefferson's goals for it. Lewis also received permission to choose a co-captain to assist him with the responsibilities of managing men and supplies, making maps, and meeting with American Indian tribes, while recording the details in daily journal entries. For this important post Lewis turned to his old army friend William Clark.

Clark spent the winter of 1804 establishing a training camp for the "Corps of Discovery" at Camp Wood, which was located 18 miles north of St. Louis at the confluence of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers. Meanwhile, Lewis was in St. Louis, Cahokia, and Kaskaskia arranging for supplies and equipment for the journey. Lewis also spent time obtaining information about the newly acquired Louisiana Territory through people who were involved with the fur trade on the Missouri River and who had dealings with the Native Americans who lived there.

On May 14, 1804, the Corps of Discovery, led by William Clark, set out on their journey up the Missouri River. Lewis traveled overland from St. Louis to join the group on the second day of the trip, when they reached St. Charles. Meriwether Lewis was 30 years old during that first summer of the expedition, while Clark was 34. They were young men pursuing the dream of their President, serving as his eyes and ears while trying to survive to tell the story. A year and a half and more than 4,000 miles later, the expedition reached the Pacific Ocean. Lewis was fascinated with the Native Americans, plants, animals, fossils, geological formations, topography and other facets of the trip, all of which he recorded in his journal entries. Even with all of this information, new to science, Lewis was plagued with the minor failures of his journey. He had failed to discover an all-water route to the Pacific Ocean, and also failed to set up diplomatic alliances with American Indian people to create an exclusive Rocky Mountain fur trade for the United States.

The expedition ended at St. Louis in 1806, and Lewis returned to Washington, D.C. to report to President Jefferson in person. Both Lewis and Clark were rewarded for their success. Meriwether Lewis was appointed to the governorship of the Louisiana Territory, while William Clark became the Indian Agent for the far west. Lewis returned to St. Louis to assume his new office. While attending to his duties as governor, Lewis planned to find an editor and publisher for the expedition journals, but there always seemed to be more pressing business to attend to in the territory.

Being governor of the sprawling Upper Louisiana Territory proved challenging. In 1808, St. Louis was still a rowdy frontier town on the edge of a wilderness, whose dominant business was the fur trade. Lewis was often attacked by factions in St. Louis, many of whom were interested in wresting land from the former French inhabitants. Lewis was frequently at odds with Gen. James Wilkinson, the top ranking officer in the U.S. Army, and even his own Lt. Governor, Frederick Bates, who openly conspired against him and insulted him in public. There is evidence that Lewis supported editor Joseph Charless and his Missouri Gazette, the first and only newspaper in St. Louis at the time, to counteract propaganda put forth by his political enemies. Lewis failed at many aspects of the governorship, however, most notably in the public perception of how he spent official government funds. His involvement in the St. Louis-Missouri River Fur Company, and its funding by the U.S. Government, was questioned, as was money spent on a draft for official purposes, for which Lewis had not been given advance authorization.

In an effort to explain his actions, Lewis decided to make the long journey to Washington, D.C. to try to clear his name. In early September 1809 he began his trip down the Mississippi River and arrived at Fort Pickering (in modern-day Memphis, Tennessee) on September 15. On September 29, he left the fort and planned to follow the Natchez Trace, a heavily-traveled wilderness road. Accompanying him on horseback was Major James Neely, Lewis’ servant Pernier, and Neely’s servant. After a few days' travel the group stopped at Grinder’s Stand to stay the night. This back country inn, a cluster of log cabins and shacks, was located near present day Hohenwald, Tennessee, about seventy-two miles from Nashville.

In the early morning hours of October 11, 1809, shots rang out in the Grinder's Stand cabin where Lewis was staying. To this day it is not completely certain what happened. It is known that Governor Lewis died of two gunshot wounds, one to the head, the other to the chest. He was only 35 years old. Most historians believe that Meriwether Lewis committed suicide due to depression and problems in his life and career, while a popular belief continues that he was murdered, perhaps by representatives of his political enemies. The explorer was buried not far from where he died, and today a memorial along the Natchez Trace National Historic Trail pays tribute to the man who led the Voyage of Discovery to the Pacific Ocean. Lewis died without clearing his name, without publishing the journals which were his claim to international importance, and unmarried, with no descendants to continue his legacy. Although unrealized during his lifetime, Meriwether Lewis' accomplishments were numerous, and they made an enormous impact on our country’s perceptions and knowledge of the West.