CHAPTER XXIV.

Souwanas's Love for Souwanaquenapeke—How Nanahboozhoo Cured a Little Girl Bitten by a Snake—How the Rattlesnake got Its Rattle—The Origin of Tobacco—Nanahboozhoo in Trouble.

Wahkiegun, as Souwanas named the home of his white friends, always had a warm welcome for Souwanas. Little Souwanaquenapeke had learned to love him and nothing gave the grave old man greater pleasure than to have charge of her for hours at a time. He often carried her away to his wigwam and with great delight explained to visiting Indians how his name was woven into that of the first little paleface born among his people.

Sagastao and Minnehaha, while of course pleased to see the love of the old chief for their sweet little sister, were sometimes a little impatient when they found that he would have his hour with her before they could draw a Nanahboozhoo story out of him.

"You are all right," he would say in his dry, humorous way, "as far as you go; you are only Crees," he would add with a smile, referring to the fact that they had been born among the Cree Indians farther north; "but Souwanaquenapeke is better, as she is a pure Saulteaux."

This of course would put Sagastao and Minnehaha on the defensive, for in those days their own pride of birth was that they were Cree Indians. Faithful old Mary, herself a Cree, would of course take their part, and it was very amusing—laughable at times—to listen to the wordy strife. In these discussions Mary was always the one to first lose her temper. When this happened the penalty was to have the children throw a shawl over her head and thus silence her. From their loving hands she quietly took her punishment and was soon restored to good nature. Good-hearted Souwanas then speedily responded to the call for a story. But the little Souwanaquenapeke must be, if awake, in his arms, or, if asleep, in a little hammock or native cradle beside him.

"What is it to be about to-day?" asked the old man, as the children, full of eager anticipation, drew a couple of chairs up before him.

After some discussion Souwanas decided to tell them the Nanahboozhoo story of how he lessened the power of the rattlesnakes to do harm.

"Nanahboozhoo, in starting off one day from his grandmother's wigwam, had put on the disguise of a fine young hunter. He had not gone many miles on his journey before he came to a little tent on the edge of the forest where he found a young Indian mother full of grief over her sick child. Nanahboozhoo could not but feel very sorry for her, especially when he heard her story that a snake had crawled noiselessly into her tent and had bitten her little girl while she slept. Nanahboozhoo felt such pity, both for the weeping mother and the bitten child, that at once he set to work to counteract the sad doings of the snake. He hurriedly went into the forest, and there finding a certain plant he said, 'From this day forward the root of this plant shall be a remedy for all people against the bites of snakes.'

"Then Nanahboozhoo showed the mother that the roots were to be pounded and made into a drink and a poultice. The glad mother quickly carried out his instructions and the little girl was soon well again. The Indians have ever since been very thankful to Nanahboozhoo for letting them know of this plant, which they still use for such purposes and which they call snakeroot. Nanahboozhoo remained until he saw that the little girl was quite recovered. Then he said:

"'Now I will fix that snake so that he will not be able to do so much harm in the future.'

"Then going out he caught the king of the snakes and gave him a great scolding for the meanness of that one of his family which had crawled into the tent of the Indian mother and so cruelly bitten that little girl while she slept. Then getting very angry, for Nanahboozhoo was very quick-tempered, he said:

"'Snakes, like other things, have the right to live. They are given their place in the world, and their work. They are to keep down the mice, rats, frogs, toads, and other things that might become too numerous. They have their poisons given them to defend themselves if attacked. But they have no right to go and kill or injure anyone doing them no harm. I'll teach you snakes that in future you cannot quietly crawl about and bite innocent people thus.'

"So he took a piece of the wampum from one of the strings with which he had decorated himself, and having carefully carved the hard shells of which wampum is made, Nanahboozhoo firmly fastened them to the snake's tail, and said:

"'From this day forward may all snakes like you have those noisy rattles upon them, so that all people will call you rattlesnakes. And may it be that you can never move without making a noise with those rattles, so that people will always be able to hear them and thus get ready to fight you, or to get out of your way before you can do any harm.'"

"Well done, Nanahboozhoo!" shouted little Sagastao. "He's the one for me. But why did he not kill all the rattlesnakes at once?"

Souwanas was, however, too clever to be caught trying to answer a question that, although asked by a child, was beyond his knowledge, so he resorted to his calumet, and as the smoke of it began to taint the air Sagastao said, "Well, Souwanas, can you tell us where you Indians first got your tobacco?"

This question was more to the taste of the old Indian, so while he smoked he related the tradition of the introduction of tobacco among his people.

"Very many winters ago," said he, "as Nanahboozhoo was traveling on one of his long journeys he visited a land of great high mountains. One day as he was passing a great chasm in the mountains he saw some blue smoke slowly coming up out of it. This excited his curiosity and he went to see what caused it. As he drew near to it he was very much pleased with its odor. On further investigation he found that the great cave from which the smoke arose was inhabited by a giant who was the keeper of tobacco.

"Nanahboozhoo, on searching, found him half asleep in this cave among great bales and bags of tobacco.

"The smell of the smoke of the tobacco had so pleased Nanahboozhoo that he asked the giant to give him some. The giant refused in a very surly fashion, saying that he only gave portions of it away to his friends the Munedoos, who came once a year to smoke with him.

"Nanahboozhoo, seeing that he was not going to be able to get any by thus pleading for it, snatched up one of the well-filled tobacco bags, dashed out with it, and fled away as rapidly as possible. The great giant was fearfully enraged, and at once began the pursuit of this rash fellow who had thus stolen his tobacco from under his very nose.

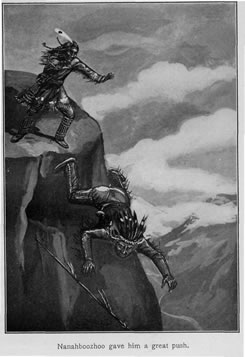

"It was a fearful race. Nanahboozhoo had to jump from one mountain top to the next, and so on and on from peak to peak. Closely behind him followed the giant, and Nanahboozhoo had all he could do to keep from being captured. Fortunately for him he now knew the mountains well, and he remembered one ahead of him the opposite side of which was very steep. When he reached this top he suddenly threw himself down upon the very edge, and as the giant passed over him Nanahboozhoo suddenly sprang up and gave him such a push that he tumbled down into the fearful chasm. He was so bruised and wounded that, as he got up and hobbled away down the far-off valley, Nanahboozhoo watching him saw that he looked just like a great grasshopper. He burst out laughing, and then shouted to the giant:

"'For your meanness and selfishness I change you into a grasshopper; Pukaneh shall be your name and you will always have a dirty mouth.'

"And so it is to this day, for every little boy who has caught grasshoppers knows that their saliva is as though they had been chewing tobacco.

"When Nanahboozhoo had rested himself a little he returned to the cave of the giant and took possession of the great quantities of tobacco he found there. He divided it among the Indian tribes, and from that time those who live where it will grow have cultivated it and have supplied all the others."

"I wish," said Minnehaha, "that Nanahboozhoo had left Pukaneh and his tobacco in the cave, for I don't think tobacco smoke is very nice in the house."

Souwanas was amused with the little girl's opposition to his beloved weed, and while she was talking took the opportunity to refill his calumet. When it was in good smoking order he, urgently requested by Sagastao, resumed his story-telling.

"Sometimes it did not fare so well with Nanahboozhoo. There were times when his cleverness seemed to forsake him, and he got into trouble' that at other times he would easily have avoided. For example, one day in the summer time as he was hurrying along he became very thirsty. Soon, however, he came to a river which has many trees on its banks. He pushed his way through them until he came to the bank. Just as he was stooping down to drink he saw some nice ripe fruit in the water. Without seeming to think of what he was doing he dived into the quite shallow water to get the fruit, hit his head against the rocky bottom and was pretty badly hurt. He was vexed and angry as well as disappointed, but he took a good drink of the water and then he lay down on the grass in the shade of the trees to rest. As he lay there on his back he saw above him on the branches of the trees the fruit which he had at first thought was in the water.

"Laughing at his own stupidity and climbing up into the trees he soon had all the ripe fruit he could eat.

"Then on he went, and as his head was quite sore from the bump he had got when he dived into the shallow river he determined to visit some wigwams which he saw not far off.

"The people received him very kindly, with the exception of one surly, cross old man. They quickly prepared some balsam and put it on his wounded head.

"Nanahboozhoo was well pleased with this kindness, and said that he would be glad to perform for them some kindly act in return.

"Before anyone else, however, could speak the cross old man sneered out:

"'O, if you think you are clever enough to do anything, grant that I may live forever!'

"This request and the sneering way in which it was made caused the quick-tempered Nanahboozhoo to become very angry, and he suddenly sprang up and caught the Indian by the shoulders and violently throwing him on the ground said:

"'From this time you shall be a stone, and so your request is granted.'"