Valley Forge

"To see men without clothes to cover their nakedness, without blankets to lie upon, without shoes ... without a house or hut to cover them until those could be built, and submitting without a murmur, is a proof of patience and obedience which, in my opinion, can scarcely be paralleled."-George Washington at Valley Forge,

April 21, 1778

Of all the places associated with America's War for Independence, none conveys more the impression of suffering, sacrifice, and ultimate triumph than Valley Forge. No battles were fought here, no bayonet charges or artillery bombardments took place, but during the winter of 1777-78 approximately 2,000 soldiers died at hospitals in the surrounding area nonetheless. Valley Forge is the story of an army's epic struggle to survive against terrible odds, against hunger, disease, and the unrelenting forces of nature.

The campaign that resulted in the Valley Forge encampment began in late August 1777 when Sir William Howe, commander in chief of British forces in North America, landed his veteran army at the upper end of Chesapeake Bay. His objective was Philadelphia, the patriot capital. The American commander, George Washington, maneuvered the Continental Army into position to defend the city. Howe's skillful tactics, combined with errors made by Washington's army, led to a British victory at the Brandywine; the flight of the Continental Congress to York, Pa.; the British occupation of Philadelphia; and a defeat at Germantown.

With the winter setting in, the prospects for further campaigning were greatly diminished, and Washington sought quarters for his men. Though several locations were proposed, he selected Valley Forge, 18 miles northwest of Philadelphia. It proved to be an excellent choice. Named for an iron forge on Valley Creek, the area was close enough to the British to keep their raiding and foraging parties out of the interior of Pennsylvania, yet far enough away to halt the threat of British surprise attacks. The high ground of Mount Joy and Mount Misery, combined with the Schuylkill River to the north, made the area easily defensible.

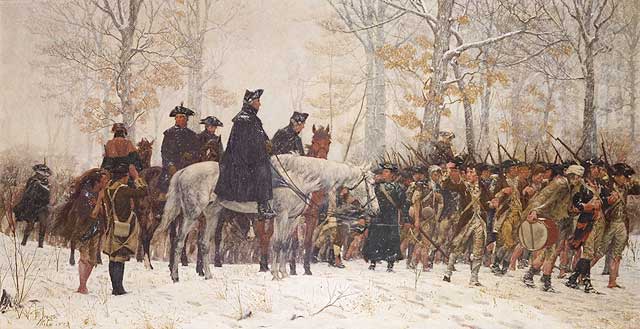

On December 19, 1777, when Washington's poorly fed, ill-equipped army, weary from long marches, struggled into Valley Forge, winds blew as the 12,000 Continentals prepared for winter's fury. Grounds for brigade encampments were selected, and defense lines were planned and begun. Within days of the army's arrival, the Schuylkill River was covered with ice. Snow was six inches deep. Though construction of more than 1,000 huts provided shelter, it did little to offset the critical shortages that continually plagued the army.

Soldiers received irregular supplies of meat and bread, some getting their only nourishment from "firecake,"" a tasteless mixture of flour and water. So severe were conditions at times that Washington despaired "that unless some great and capital change suddenly takes place ... this Army must inevitably ... Starve, dissolve, or disperse, in order to obtain subsistence in the best manner they can." Animals fared no better. Gen. Henry Knox, Washington's Chief of Artillery, wrote that hundreds of horses either starved to death or died of exhaustion.

Clothing, too, was wholly inadequate. Long marches had destroyed shoes. Blankets were scarce. Tattered garments were seldom replaced. At one point these shortages caused nearly 4,000 men to be listed as unfit for duty.

Undernourished and poorly clothed, living in crowded, damp quarters, the army was ravaged by sickness and disease. Typhus, typhoid, dysentery, and pneumonia were among the killers that felled as many as 2,000 men that winter. Although Washington repeatedly petitioned for relief, the Congress was unable to provide it, and the soldiers continued to suffer. Women, relatives of enlisted men, alleviated some of the suffering by providing valuable services such as laundry and nursing that the army desperately needed.

Upgrading military efficiency, morale, and discipline were as vital to the army's well-being as was its source of supply. The army had been handicapped in battle because unit training was administered from a variety of field manuals, making coordinated battle movements awkward and difficult. The soldiers were trained, but not uniformly. The task of developing and carrying out an effective training program fell to Baron Friedrich von Steuben. This skilled Prussian drillmaster, recently arrived from Europe, tirelessly drilled and scolded the regiments into an effective fighting force. Intensive daily training, coupled with von Steuben's forceful manner, instilled in the men renewed confidence in themselves and their ability to succeed.

The passing weeks of winter saw the army, under Washington's inspirational leadership, undergo a dramatic transformation. Slowly but steadily the endurance, bravery, and sacrifice of the soldiers began to tell. Increasing amounts of supplies and equipment came into camp. New troops arrived. Spring brought word of the French alliance with its guarantees of military support. Now a strong, dependable force, well-trained and hopeful of success, drilled on the Grand Parade.

Soon word of the British departure from Philadelphia brought a frenzied activity to the ranks of the Continental Army. On June 19, 1778, six months after its arrival, the army marched away from Valley Forge in pursuit of the British who were moving toward New York. An ordeal had ended. The war would last for another five years, but for Washington, his men, and the nation to which they sought to give birth, a decisive victory had been won -- a victory not of weapons but of will. The spirit of Valley Forge was now a part of the army and because of it the prospects for final victory were considerably brighter.

(Much of the information in this section was adapted from resources provided by the National Park Service.)