American Indians

By

Frederick Starr

D. C. Heath & Co., Publishers

Boston, New York, Chicago

1898

Contents

- Preface.

- I. Some General Facts About Indians.

- II. Houses.

- III. Dress.

- IV. The Baby And Child.

- V. Stories Of Indians.

- VI. War.

- VII. Hunting And Fishing.

- VIII. The Camp-Fire.

- IX. Sign Language On The Plains.

- X. Picture Writing.

- XI. Money.

- XII. Medicine Men And Secret Societies.

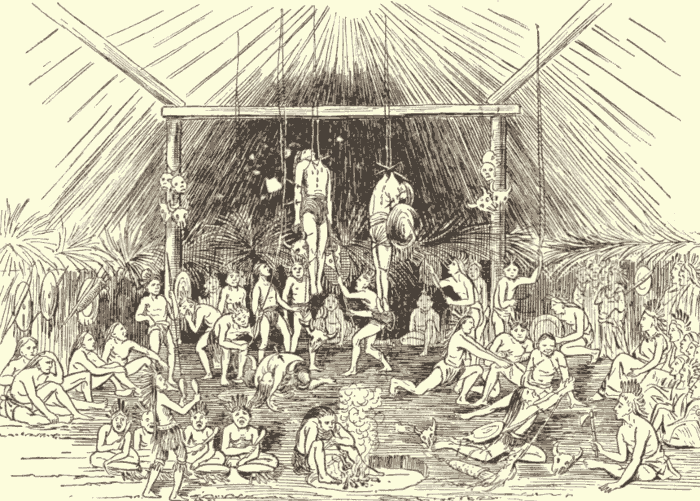

- XIII. Dances And Ceremonials.

- XIV. Burial And Graves.

- XV. Mounds And Their Builders.

- XVI. The Algonkins.

- XVII. The Six Nations.

- XVIII. Story Of Mary Jemison.

- XIX. The Creeks.

- XX. The Pani.

- XXI. The Cherokees.

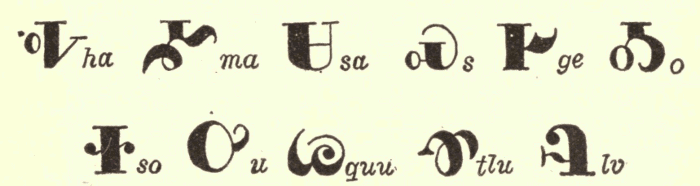

- XXII. George Catlin And His Work.

- XXIII. The Sun Dance.

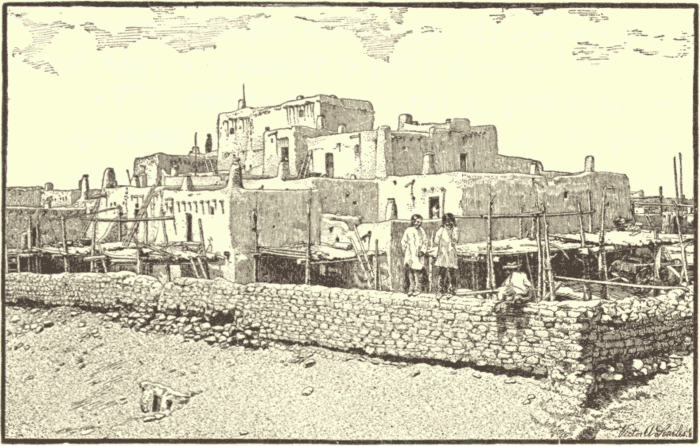

- XXIV. The Pueblos.

- XXV. The Snake Dance.

- XXVI. Cliff Dwellings And Ruins Of The Southwest.

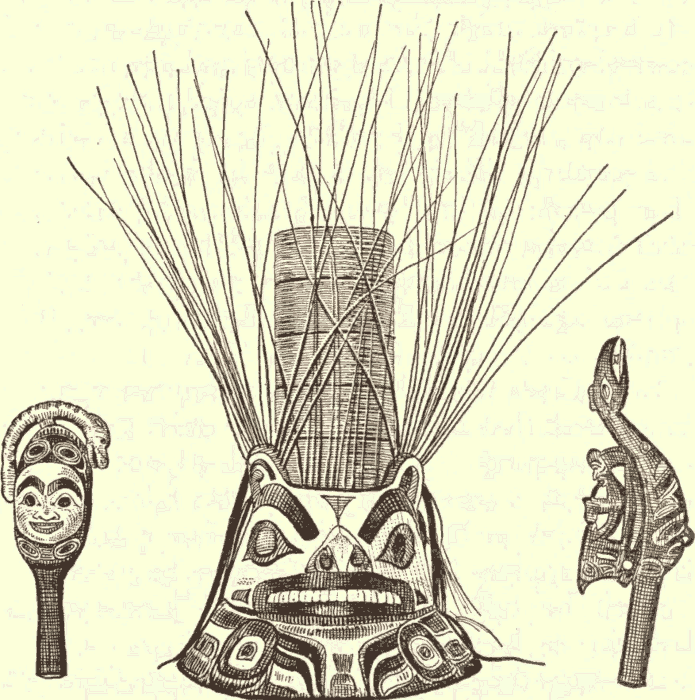

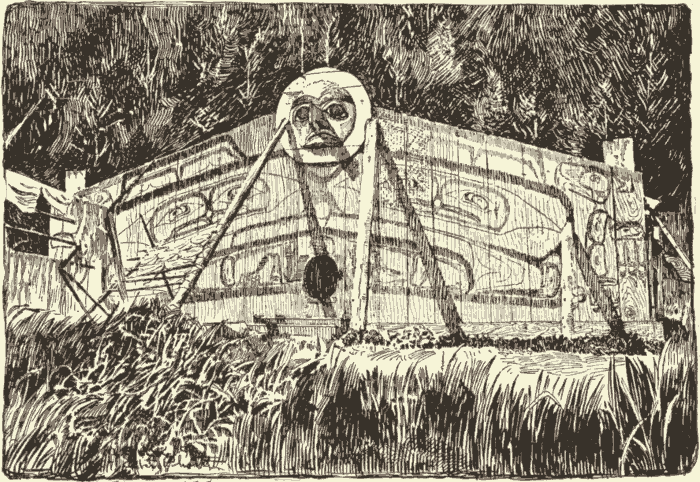

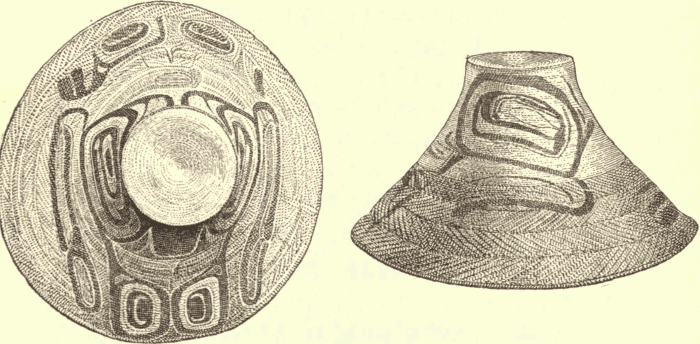

- XXVII. Tribes Of The Northwest Coast.

- XXVIII. Some Raven Stories.

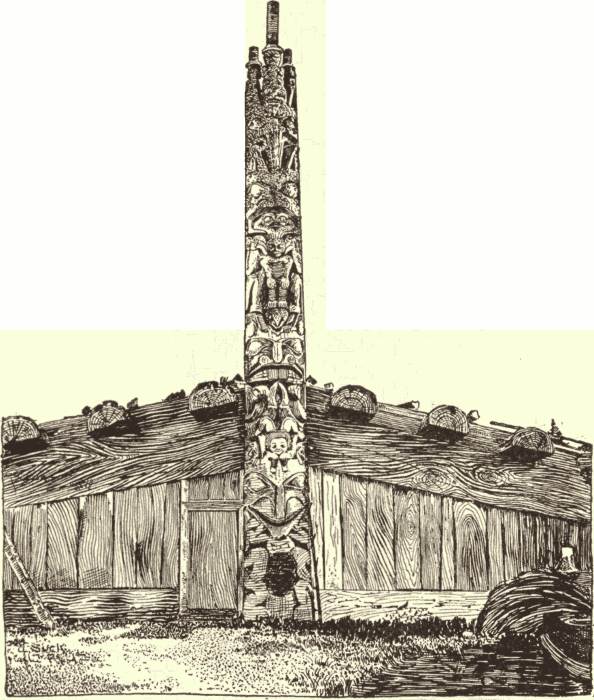

- XXIX. Totem Posts.

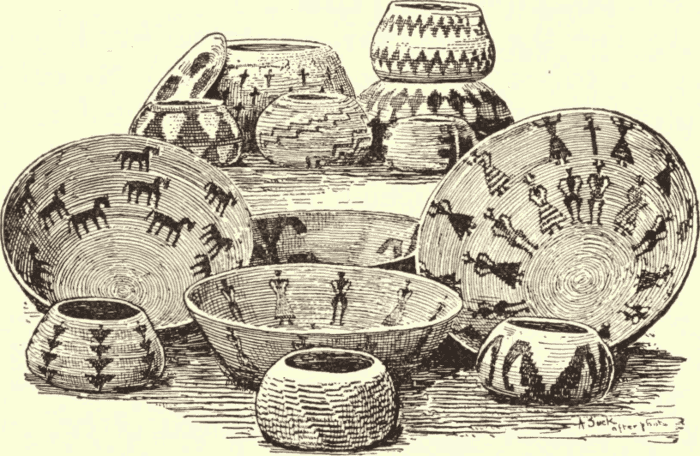

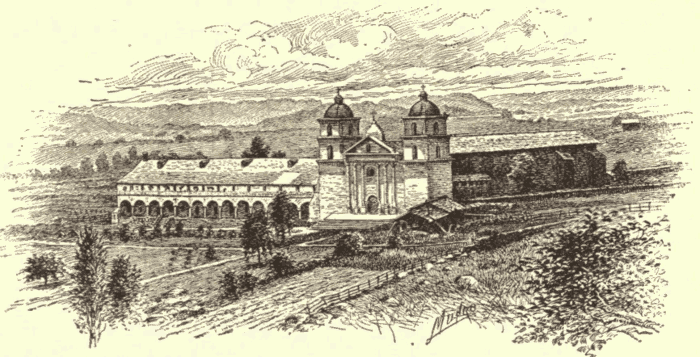

- XXX. Indians Of California.

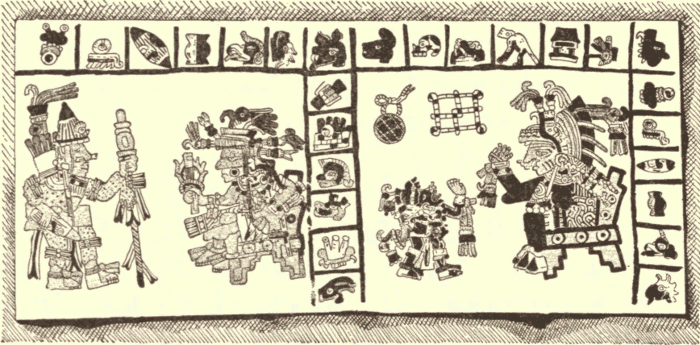

- XXXI. The Aztecs.

- XXXII. The Mayas And The Ruined Cities Of Yucatan And Central America.

- XXXIII. Conclusion.

- Glossary Of Indian And Other Foreign Words Which May Not Readily Be Found In The English Dictionary.

- Index.

- Footnotes

Preface.

This book about American Indians is intended as a reading book for boys and girls in school. The native inhabitants of America are rapidly dying off or changing. Certainly some knowledge of them, their old location, and their old life ought to be interesting to American children.

Naturally the author has taken material from many sources. He has himself known some thirty different Indian tribes; still he could not possibly secure all the matter herein presented by personal observation. In a reading book for children it is impossible to give reference acknowledgment to those from whom he has drawn. By a series of brief notes attention is called to those to whom he is most indebted: no one is intentionally omitted.

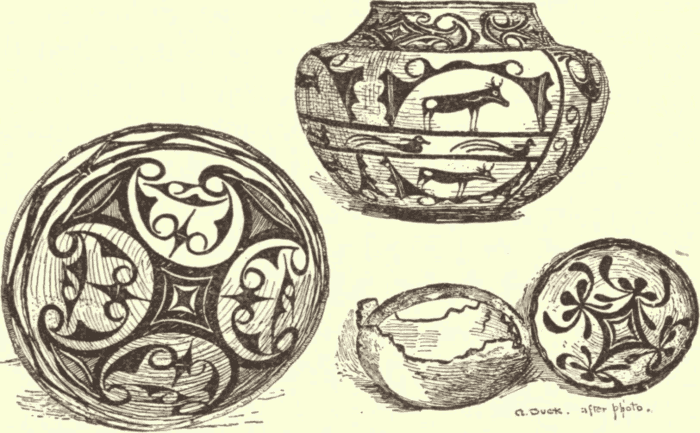

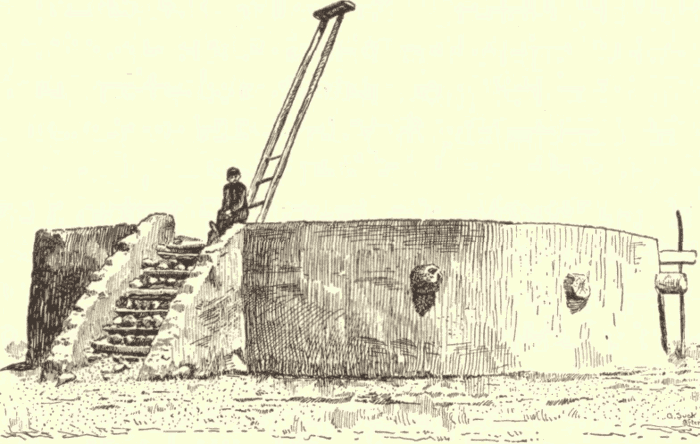

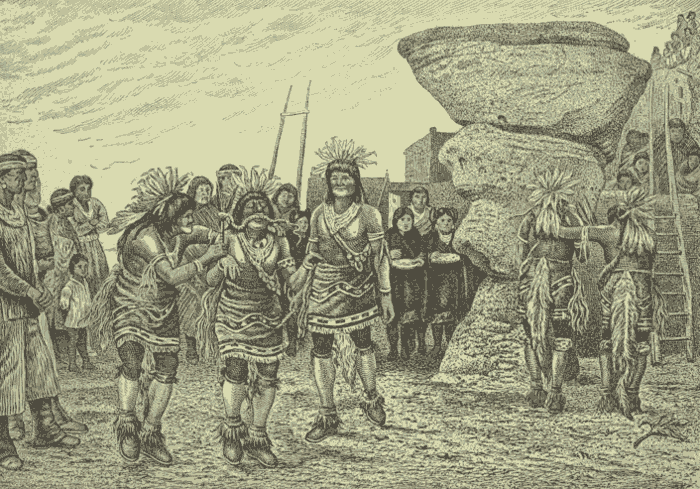

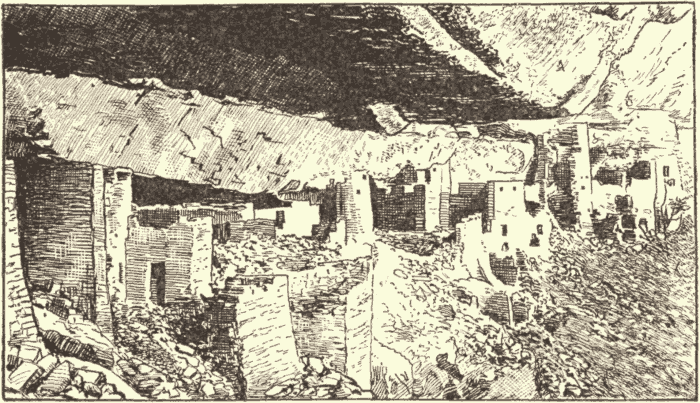

While many of the pictures are new, being drawn from objects or original photographs, some have already appeared elsewhere. In each case, their source is indicated. Special thanks for assistance in illustration are due to the Bureau of American Ethnology and to the Peabody Museum of Ethnology at Cambridge, Mass. [pg vi]

While intended for young people and written with them only in mind, the author will be pleased if the book shall interest some older readers. Should it do so, may it enlarge their sympathy with our native Americans.

I. Some General Facts About Indians.

We all know how the native Americans found here by the whites at their first arrival, came to be called Indians. Columbus did not realize the greatness of his discovery. He was seeking a route to Asia and supposed that he had found it. Believing that he had really reached the Indies, for which he was looking, it was natural that the people here should be called Indians.

The American Indians are often classed as a single type. They are described as being of a coppery or reddish-brown color. They have abundant, long, straight, black hair, and each hair is found to be almost circular when cut across. They have high cheek-bones, unusually prominent, and wide faces. This description will perhaps fit most Indians pretty well, but it would be a great mistake to think that there are no differences between tribes: there are many. There are tribes of tall Indians and tribes of short ones; some that are almost white, and others that are nearly black. There are found among them all [pg 002] shades of brown, some of which are reddish, others yellowish. There are tribes where the eyes appear as oblique or slanting as in the Chinese, and others where they are as straight as among ourselves. Some tribes have heads that are long and narrow; the heads of others are relatively short and wide. A little before the World's Columbian Exposition thousands of Indians of many different tribes were carefully measured. Dr. Boas, on studying the figures, decided that there were at least four different types in the United States.

There are now living many different tribes of Indians. Formerly the number of tribes was still greater. Each tribe has its own language, and several hundred different Indian languages were spoken. These languages sometimes so much resemble each other that they seem to have been derived from one single parent language. Thus, when what is now New York State was first settled, it was largely occupied by five tribes—the Mohawks, Oneidas, Onondagas, Cayugas, Senecas—called "the Five Nations." While they were distinct and each had its own language, these were so much alike that all are believed to have grown from one. When languages are so similar that they may be believed to have come from one parent language, they are said to belong to the same language family or stock.

The Indians of New England, the lower Hudson region, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Virginia, [pg 003] formed many different tribes, but they all spoke languages of one family. These tribes are called Algonkins. Indians speaking languages belonging to one stock are generally related in blood. Besides the area already named, Algonkin tribes occupied New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, a part of Canada, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and other districts farther west. The Blackfeet, who were Algonkins, lived close to the Rocky Mountains. So you see that one linguistic family may occupy a great area. On the other hand, sometimes a single tribe, small in numbers and occupying only a little space, may have a language entirely peculiar. Such a tribe would stand quite alone and would be considered as unrelated to any other. Its language would have to be considered as a distinct family or stock.

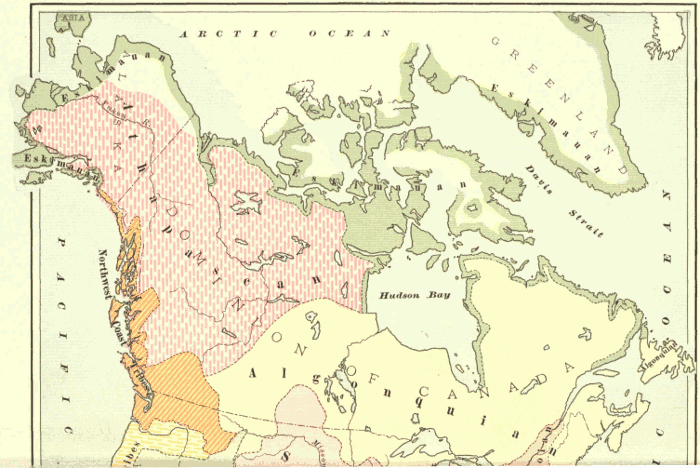

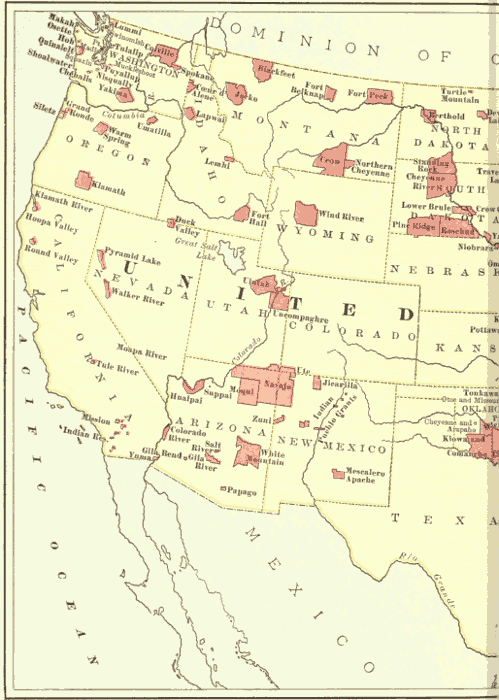

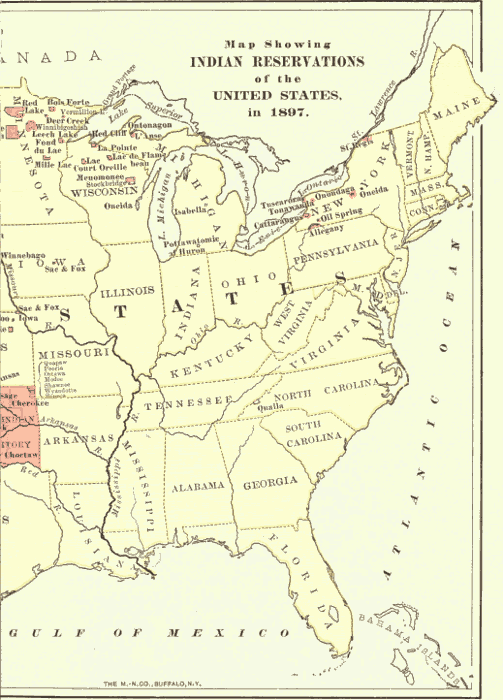

A few years ago Major Powell published a map of America north of Mexico, to show the distribution of the Indian language families at the time of the white settlement of this country. In it he represented the areas of fifty-eight different families or stocks. Some of these families, like the Algonquian and Athapascan, occupied great districts and contained many languages; others, like the Zuñian, took up only a few square miles of space and contained a single tribe. At the front of this book is a little map partly copied from that of Major Powell. The large areas are nearly as he gave them; many smaller areas of his map are omitted, as we shall not speak of them. The [pg 004] Indians of the Pueblos speak languages of at least four stocks, which Major Powell indicates. We have covered the whole Pueblo district with one color patch. We have grouped the many Californian tribes into one: so, too, with the tribes of the Northwest Coast. There are many widely differing languages spoken in each of these two regions. This map will show you where the Indians of whom we shall speak lived.

Many persons seem to think that the Indian was a perpetual rover,—always hunting, fishing, and making war,—with no settled villages. This is a great mistake: most tribes knew and practiced some agriculture. Most of them had settled villages, wherein they spent much of their time. Sad indeed would it have been for the early settlers of New England, if their Indian neighbors had not had supplies of food stored away—the result of their industry in the fields.

The condition of the woman among Indians is usually described as a sad one. It is true that she was a worker—but so was the man. Each had his or her own work to do, and neither would have thought of doing that of the other; with us, men rarely care to do women's work. The man built the house, fortified the village, hunted, fished, fought, and conducted the religious ceremonials upon which the success and happiness of all depended. The woman worked in the field, gathered wood, tended the fire, cooked, dressed skins, and cared for the children. When they [pg 005] traveled, the woman carried the burdens, of course: the man had to be ready for the attack of enemies or for the killing of game in case any should be seen. Among us hunting, fishing, and dancing are sport. They were not so with the Indians. When a man had to provide food for a family by his hunting and fishing, it ceased to be amusement and was hard work. When Indian men danced, it was usually as part of a religious ceremony which was to benefit the whole tribe; it was often wearisome and difficult—not fun. Woman was much of the time doing what we consider work; man was often doing what we consider play; there was not, however, really much to choose between them.

The woman was in most tribes the head of the house. She exerted great influence in public matters of the tribe. She frequently decided the question of peace and war. To her the children belonged. If she were dissatisfied with her husband, she would drive him from the house and bid him return to his mother. If a man were lazy or failed to bring in plenty of game and fish, he was quite sure to be cast off.

While he lived his own life, the Indian was always hospitable. The stranger who applied for shelter or food was never refused; nor was he expected to pay. Only after long contact with the white man, who always wanted pay for everything, did this hospitality disappear. In fact, among some tribes it has not yet entirely gone. One time, [pg 006] as we neared the pueblo of Santo Domingo, New Mexico, the old governor of the pueblo rode out to meet us and learn who we were and what we wanted. On explaining that we were strangers, who only wished to see the town, we were taken directly to his house, on the town square. His old wife hastened to put before us cakes and coffee. After we had eaten we were given full permission to look around.

We shall consider many things together. Some chapters will be general discussions of Indian life; others will discuss special tribes; others will treat of single incidents in customs or belief. Some of the things mentioned in connection with one particular tribe would be equally true of many others. Thus, the modes of hunting buffalo and conducting war, practiced by one Plains tribe, were much the same among Plains tribes generally. Some of the things in these lessons will seem foolish; others are terrible. But remember that foreigners who study us find that we have many customs which they think strange and even terrible. The life of the Indians was not, on the whole, either foolish or bad; in many ways it was wise and beautiful and good. But it will soon be gone. In this book we shall try to give a picture of it.

Franz Boas.—Anthropologist. German, living in America. Has made investigations among Eskimo and Indians. Is now connected with the American Museum of Natural History, New York.

[pg 007]John Wesley Powell.—Teacher, soldier, explorer, scientist. Conducted the first exploration of the Colorado River Cañon; Director of the U. S. Geological Survey and of the Bureau of American Ethnology. Has written many papers: among them Indian Linguistic Families of America North of Mexico.

II. Houses.

The houses of Indians vary greatly. In some tribes they are large and intended for several families; in others they are small, and occupied by few persons. Some are admirably constructed, like the great Pueblo houses of the southwest, made of stone and adobe mud; others are frail structures of brush and thatch. The material naturally varies with the district.

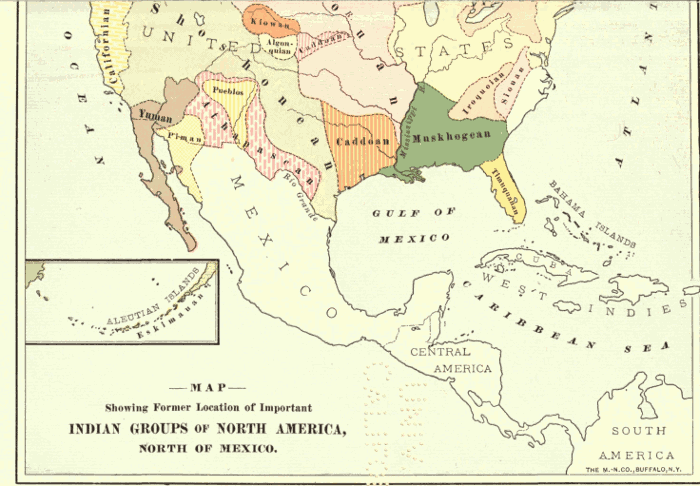

An interesting house was the "long house" of the Iroquois. From fifty to one hundred or more feet in length and perhaps not more than fifteen in width, it was of a long rectangular form. It [pg 008] consisted of a light framework of poles tied together, which was covered with long strips of bark tied or pegged on. There was no window, but there was a doorway at each end. Blankets or skins hung at these served as doors. Through the house from doorway to doorway ran a central passage: the space on either side of this was divided by partitions of skins into a series of stalls, each of which was occupied by a family. In the central passage was a series of fireplaces or hearths, each one of which served for four families. A large house of this kind might have five or even more hearths, and would be occupied by twenty or more families. Indian houses contained but little furniture. Some blankets or skins served as a bed; there were no tables or chairs; there were no stoves, as all cooking was done over the open fire or the fireplace.

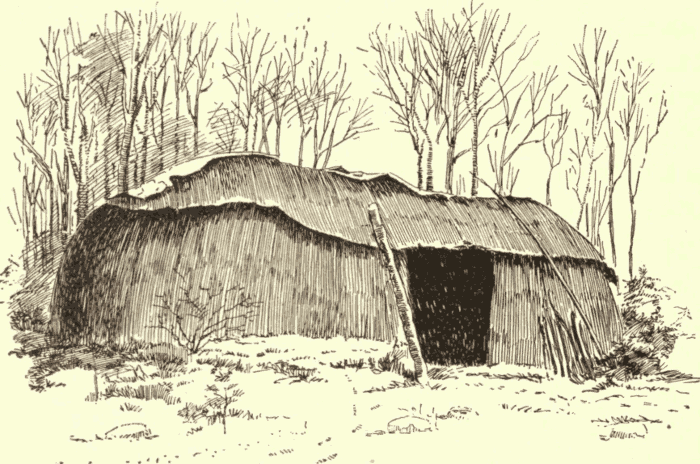

The eastern Algonkins built houses like those of the Iroquois, but usually much smaller. They, [pg 009] too, were made of a light framework of poles over which were hung sheets of rush matting which could be easily removed and rolled up, for future use in case of removal. There are pictures in old books of some Algonkin villages.

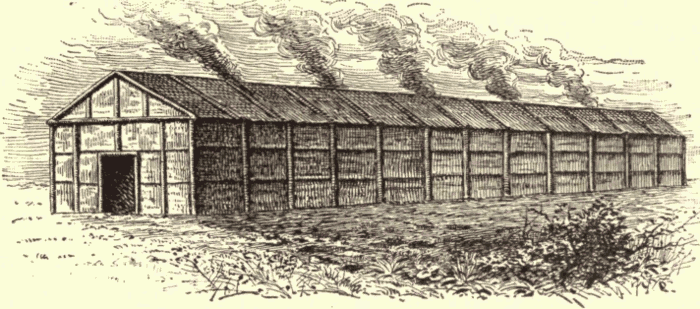

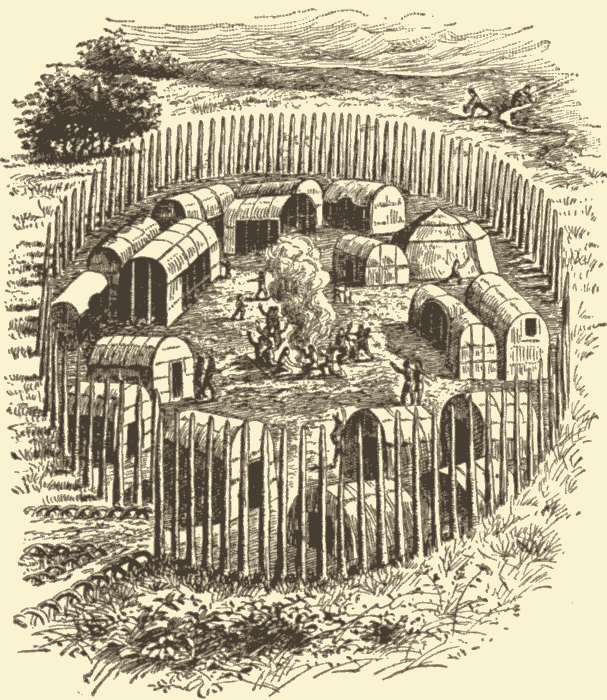

These villages were often inclosed by a line of palisades to keep off enemies. Sometimes the gardens and cornfields were inside this palisading, sometimes outside. The houses in these pictures usually have straight, vertical sides and queer rounded roofs. Sometimes they were arranged along streets, but at others they were placed in a ring around a central open space, where games and celebrations took place.

Many tribes have two kinds of houses, one for summer, the other for winter. The Sacs and Foxes of Iowa, in summer, live in large, rectangular, barn-like structures. These measure perhaps twenty feet by thirty. They are bark-covered and have two doorways and a central passage, somewhat like the Iroquois house. But they are not divided by partitions into sections. On each side, a platform about three feet high and six feet wide runs the full length of the house. Upon this the people sleep, simply spreading out their blankets when they wish to lie down. Each person has his proper place upon the platform, and no one thinks of trespassing upon another. At the back of the platform, against the wall, are boxes, baskets, and bundles containing the property of the different members of the household. As these platforms [pg 010] are rather high, there are little ladders fastened into the earth floor, the tops of which rest against the edge of the platform. These ladders are simply logs of wood, with notches cut into them for footholds.

The winter house is very different. In the summer house there is plenty of room and air; in the winter house space is precious. The framework of the winter lodge is made of light poles tied together with narrow strips of bark. It is an oblong, dome-shaped affair about twenty feet long and ten wide. Some are nearly circular and about fifteen feet across. They are hardly six feet high. Over this framework are fastened sheets of matting made of cat-tail rushes. This matting is very light and thin, but a layer or two of it keeps out [pg 011] a great deal of cold. There is but one doorway, usually at the middle of the side. There are no platforms, but beds are made, close to the ground, out of poles and branches. At the center is a fireplace, over which hangs the pot in which food is boiled.

The Mandans used to build good houses almost circular in form. The floor was sunk a foot or more below the surface of the ground. The framework was made of large and strong timbers. The outside walls sloped inward and upward from the ground to a height of about five feet. They were composed of boards. The roof sloped from the top of the wall up to a central point; it was made of poles, covered with willow matting and then with grass. The whole house, wall and roof, was then covered over with a layer of earth a foot and a half thick. When such a house contained a fire sending out smoke, it must have looked like a smooth, regularly sloping little volcano.

In California, where there are so many different sorts of climate and surroundings, the Indian tribes differed much in their house building. Where the climate was raw and foggy, down near the coast, they dug a pit and erected a shelter of redwood poles about it. In the snow belt, the house was conical in form and built of great slabs of bark. In warm low valleys, large round or oblong houses were made of willow poles covered with hay. At Clear Lake there were box-shaped houses; the walls were built of vertical posts, with poles [pg 012] lashed horizontally across them; these were not always placed close together, but so as to leave many little square holes in the walls; the flat roof was made of poles covered with thatch. In the great treeless plains of the Sacramento and San Joaquin they made dome-shaped, earth-covered houses, the doorway in which was sometimes on top, sometimes near the ground on the side. In the Kern and Tulare valleys, where the weather is hot and almost rainless, the huts are made of marsh rushes.

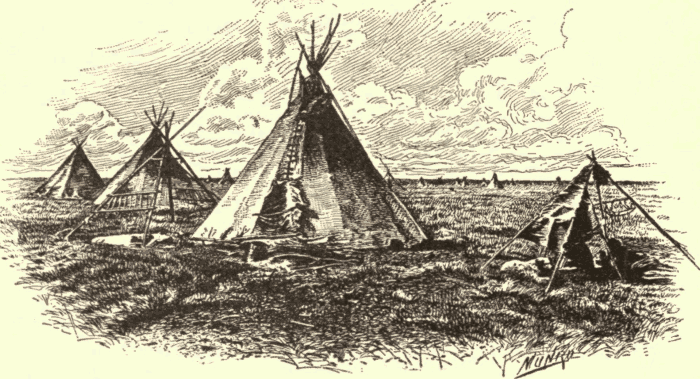

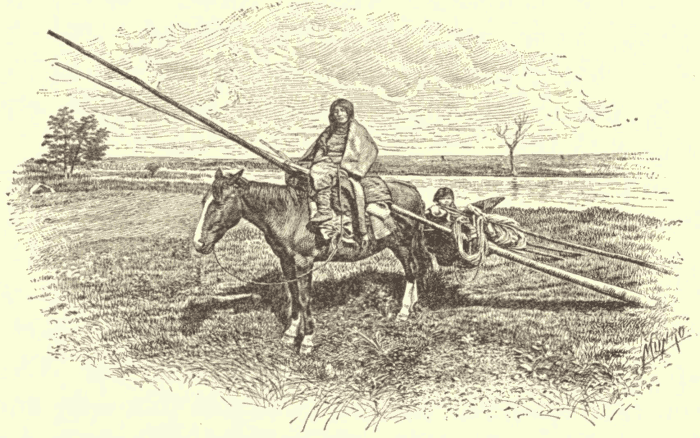

Many persons seem to think that the Indian never changes; that he cannot invent or devise new things. This is a mistake. Long ago the Dakotas lived in houses much like those of the Sacs and Foxes. At that time they lived in Minnesota, near the headwaters of the Mississippi River. From the white man they received horses, [pg 013] and by him they were gradually crowded out of their old home. After getting horses they had a much better chance to hunt buffalo, and began to move about much more than before. They then invented the beautiful tent now so widely used among Plains Indians. The framework consists of thirteen poles from fifteen to eighteen feet long. The smaller ends are tied together and then raised and spread out so as to cover a circle on the ground about ten feet across. Over this framework of poles are spread buffalo skins which have been sewed together so as to fit it. The lower end of this skin covering is then pegged down and the sides are laced together with cords, so that everything is neat and tight. There is a doorway below to creep through, over which hangs a flap of skin as a door. The smoke-hole at the top has a sort of collar-like flap, which can be adjusted when the wind changes so as to insure a good draught of air at all times.

This sort of tent is easily put up and taken down. It is also easily transported. The poles are divided into two bunches, and these are fastened by one end to the horse, near his neck—one bunch on either side. The other ends are left to drag upon the ground. The skin covering is tied up into a bundle which may be fastened to the dragging poles. Sometimes dogs, instead of horses, were used to drag the tent poles.

Among many tribes who used these tents, the camp was made in a circle. If the space was too [pg 014] small for one great circle, the tents might be pitched in two or three smaller circles, one within another. These camp circles were not chance arrangements. Each group of persons who were related had its own proper place in the circle. Even the proper place for each tent was fixed. Every woman knew, as soon as the place for a camp was chosen, just where she must erect her tent. She would never think of putting it elsewhere. After the camp circle was complete, the horses would be placed within it for the night to prevent their being lost or stolen.

Stephen Powers.—Author of The Indians of California.

III. Dress.

In the eastern states and on the Plains the dress of the Indians was largely composed of tanned and dressed skins such as those of the buffalo and the deer. Most of the Indians were skilled in dressing skins. The hide when fresh from the animal was laid on the ground, stretched as tightly as possible and pegged down all around the edges. As it dried it became still more taut. [pg 015] A scraper was used to remove the fat and to thin the skin. In old days this scraper was made of a piece of bone cut to proper form, or of a stone chipped to a sharp edge; in later times it was a bone handle, with a blade of iron or steel attached to it. Brains, livers, and fat of animals were used to soften and dress the skin. These materials were mixed together and spread over the stretched skin, which was then rolled up and laid aside. After several days, when the materials had soaked in and somewhat softened the skin, it was opened and washed: it was then rubbed, twisted, and worked over until soft and fully dressed.

The men wore three or four different articles of dress. First was the breech-clout, which consisted of a strip of skin or cloth perhaps a foot wide and several feet long; sometimes its ends were decorated with beadwork or other ornamentation. This cloth was passed between the legs and brought up in front and behind. It was held in place by a band or belt passing around the waist, and the broad decorated ends hung down from this something like aprons. Almost all male Indians on the continent wore the breech-clout.

The men also wore buckskin leggings. These were made in pairs, but were not sewed together. They fitted tightly over the whole length of the leg, and sometimes were held up by a cord at the outer upper corner, which was tied to the waist-string. [pg 016] Leggings were usually fringed with strips of buckskin sewed along the outer side. Sometimes bands of beadwork were tied around the leggings below the knees.

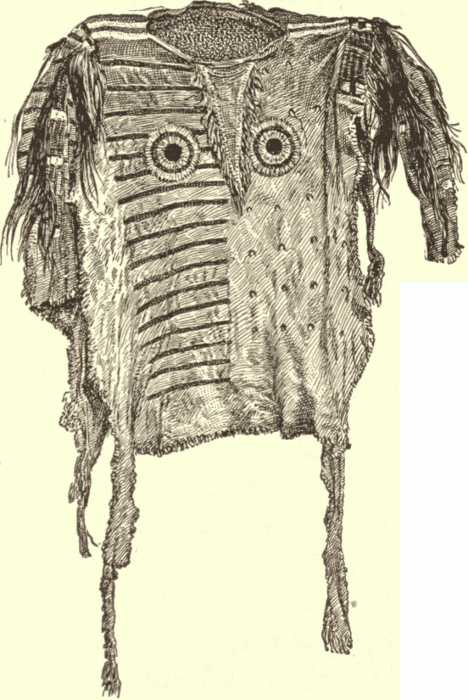

A jacket or shirt made of buckskin and reaching to the knees was generally worn. It was variously decorated. Buckskin strip fringes bordered it; pictures in black or red or other colors were painted upon it; handsome patterns were worked into it with beads or porcupine quills, brightly dyed; tufts of hair or true scalps might be attached to it.

Over all these came the blanket or robe. Nowadays these are got from the whites, and are simple flannel blankets; but in the old times they were made of animal hides. In putting on a blanket, the male Indian usually takes it by two corners, one in each hand, and folds it around him with the upper edge horizontal. Holding it thus a moment with one hand, he catches the sides, a [pg 017] little way down, with the fingers of the other hand, and thus holds it.

Even where the men have given up the old style of dress the women often retain it. The garments are usually made, however, of cloth instead of buckskin. Thus among the Sacs and Foxes the leggings of the women, which used to be made of buckskin, are now of black broad-cloth. They are made very broad or wide, and reach only from the ankles to a little above the knees. They are usually heavily beaded. The woman's skirt, fastened at the waist, falls a little below the knees; it is made of some bright cloth and is generally banded near the bottom with tape or narrow ribbon of a different color from the skirt itself. Her jacket is of some bright cloth and hangs to the waist. Often it is decorated with brooches or fibulæ made of German silver. I once saw a little girl ten years old who was dancing, in a jacket adorned with nearly three hundred of these ornaments placed close together.

All Indians, both men and women, are fond of necklaces made of beads or other material. Men love to wear such ornaments composed of trophies, showing that they have been successful in war or in hunting. They use elk teeth, badger claws, or bear claws for this purpose. One very dreadful necklace in Washington is made chiefly of the dried fingers of human victims. Among the Sacs and Foxes, the older men use a neck-ring [pg 018] that looks like a rope of solid beads. It consists of a central rope made of rags; beads are strung on a thread and this is wrapped around and around the rag ring, until when finished only beads can be seen.

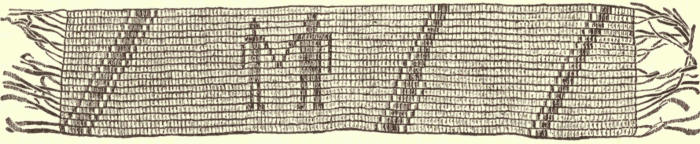

Before the white man came, the Indians used beads made of shell, stone, or bone. Nowadays they are fond of the cheap glass beads which they get from white traders. There are two kinds of beadwork now made. The first is the simpler. It is sewed work. Patterns of different colored beads are worked upon a foundation of cloth. Moccasins, leggings, and jackets are so decorated; sometimes the whole article may be covered with the bright beads. Almost every one has seen tobacco-pouches or baby-frames covered with such work. The other work is far more difficult. It is used in making bands of beads for the arms, legs, and waist. It is true woven work of the same sort as the famous wampum belts, of which we shall speak later. Such bands look like solid beads and present the same patterns on both sides.

The porcupine is an animal that is covered with spines or "quills." These quills were formerly much used in decorating clothing. They were often dyed in bright colors. After being colored they were flattened by pressure and were worked into pretty geometrical designs, color-bands, rosettes, etc., upon blankets, buckskin shirts, leggings, and moccasins. Very little of this work [pg 019] has been done of late years: beadwork has almost crowded it out of use.

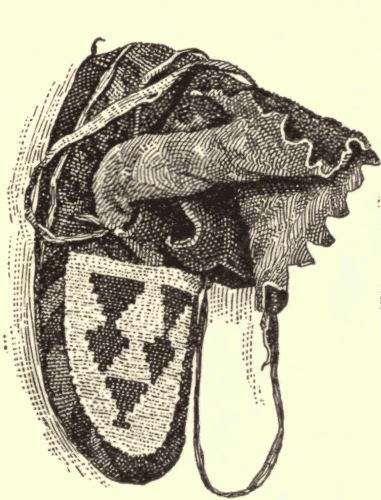

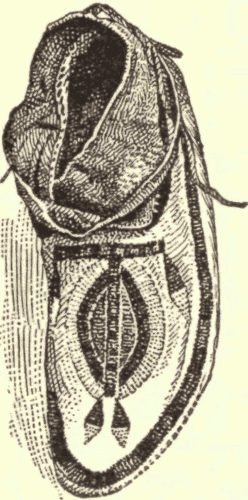

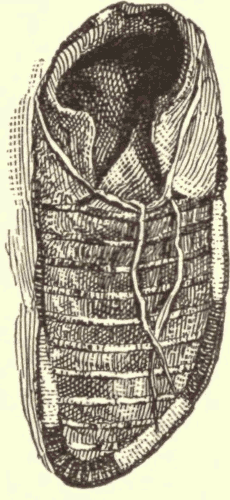

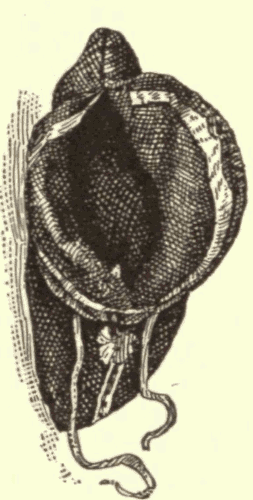

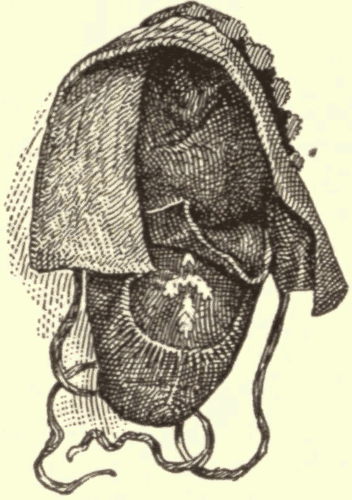

The moccasin is a real Indian invention, and it bears an Indian name. It is the most comfortable foot-wear that could be devised for the Indian mode of life. It is made of buckskin and closely fits the foot. Moccasins usually reach only to the ankle, and are tied close with little thongs of buckskin. They have no heels, and no part is stiff or unpleasant to the foot. The exact shape of the moccasin and its decoration varies with the tribe.

In some tribes there is much difference between the moccasins of men and those of women. Among the Sacs and Foxes the woman's moccasin has two side flaps which turn down and nearly reach the ground; these, as well as the part over the foot, are covered with a mass of beading; the man's moccasin has smaller side flaps, and the [pg 020] only beading upon it is a narrow band running lengthwise along the middle part above the foot.

The women of the Pueblos are not content with simple moccasins, but wrap the leg with strips of buckskin. This wrapping covers the leg from the ankles to the knees and is heavy and thick, as the strips are wound time after time around the leg. At first, this wrapping looks awkward and ugly to a stranger, but he soon becomes accustomed to it.

Not many of the tribes were real weavers. Handsome cotton blankets and kilts were woven by the Moki and other Pueblo Indians. Such are still made by these tribes for their religious ceremonies and dances. Nowadays these tribes have flocks of sheep and know how to weave good woollen blankets. Some of the Pueblos also weave long, handsome belts, in pretty patterns of bright colors. Their rude loom consists of just a few sticks, but it serves its purpose [pg 021] well, and the blankets and belts are firm and close.

The Navajo, who are neighbors of the Pueblos, learned how to weave from them, but are to-day much better weavers than their teachers. Every one knows the Navajo blankets, with their bright colors, pretty designs, and texture so close as to shed water.

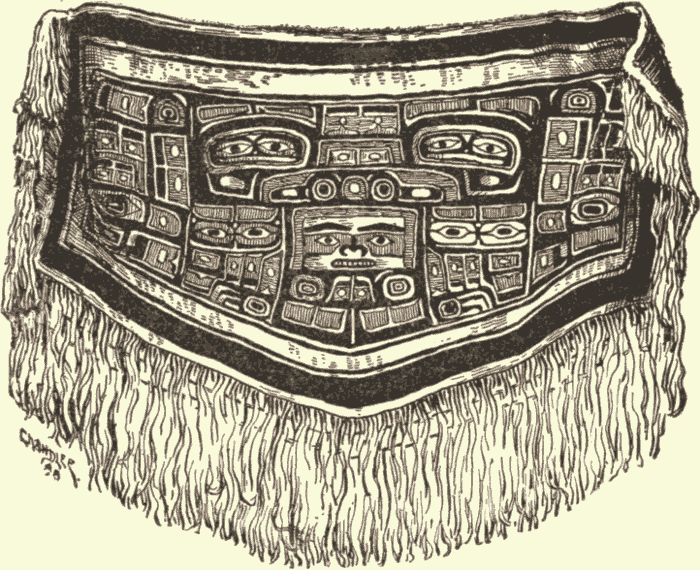

Some tribes of British Columbia weave soft capes or cloaks of cedar bark, and in Alaska the Chilcat Indians weave beautiful blankets of mountain-sheep wool and mountain-goat hair. These are a mass of odd, strikingly colored, and crowdedly arranged symbolic devices.

Among some California Indians the women wore dresses made of grass. They were short skirts or kilts, consisting of a waist-band from which hung a fringe of grass cords. They had nuts and other objects ornamentally inserted into the cords. They reached about to the knees. [pg 022]

IV. The Baby And Child.

Indian babies are often pretty. Their big black eyes, brown, soft skin, and their stiff, strong, black hair form a pleasing combination. Among many tribes their foreheads are covered with a fine, downy growth of black hair, and their eyes appear to slant, like those of the Chinese. The little fellows hardly ever cry, and an Indian parent rarely strikes a child, even when it is naughty, which is not often.

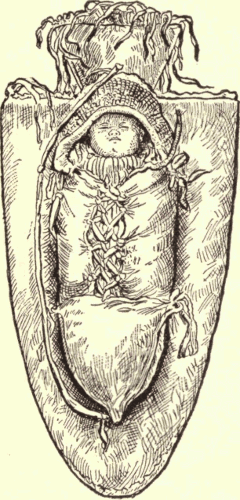

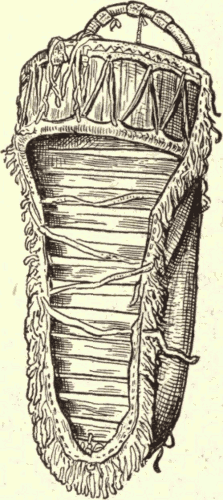

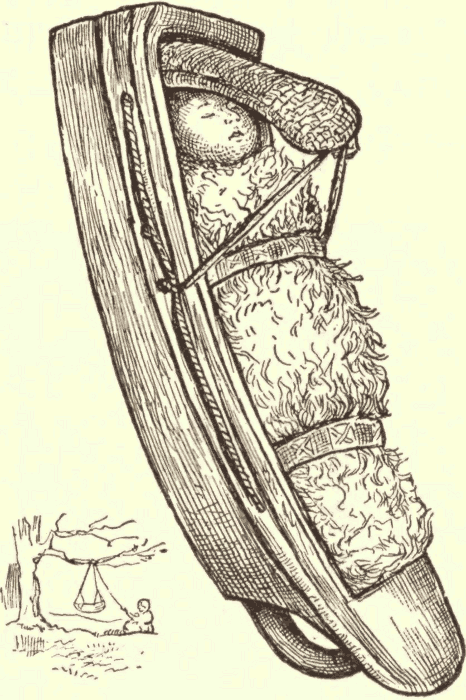

Most Indian babies are kept strapped or laid on a papoose-board or cradle-board. While these are widely used, they differ notably among the tribes. Among the Sacs and Foxes the cradle consists of a board two feet or two and a half feet long and about ten inches wide. Near the lower end is fastened, by means of thongs, a thin board set edgewise and bent so as to form a foot-rest and sides. Over the upper end is a thin strip of board bent to form an arch. This rises some eight inches above the cradle-board. Upon the board, below this arch, is a little cushion or pillow. The baby, wrapped in cloths or small blankets, his arms often being bound down to his sides, is laid down upon the cradle-board, with his head lying on the pillow and his feet reaching almost to the foot-board. He [pg 023] is then fastened securely in place by bandages of cloth decorated with beadwork or by laces or thongs. There he lies "as snug as a bug in a rug," ready to be carried on his mother's back, or to be set up against a wall, or to be hung up in a tree.

When his mother is busy at work, the little one is unwrapped so as to set his arms and hands free, and is then laid upon the blankets and cloths, and left to squirm and amuse himself as best he can.

The mother hangs all sorts of beads and bright and jingling things to the arch over the baby's head. When he lies strapped down, the [pg 024] mother sets all these things to jingling, and the baby lies and blinks at them in great wonder. When his little hands are free to move, the baby himself tries to strike and handle the bright and noisy things.

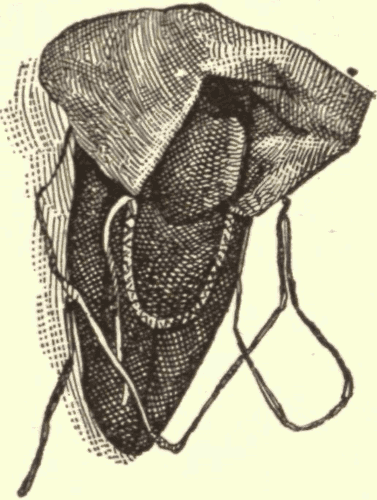

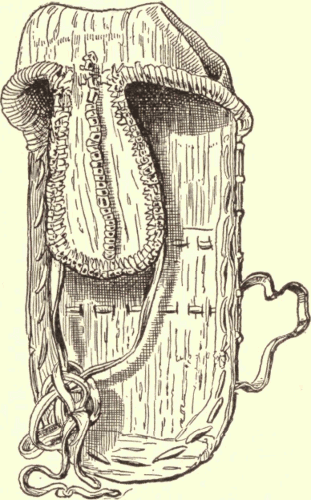

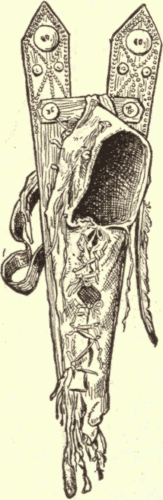

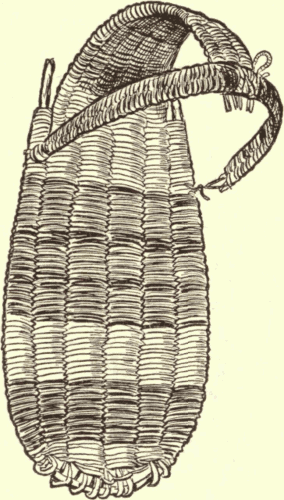

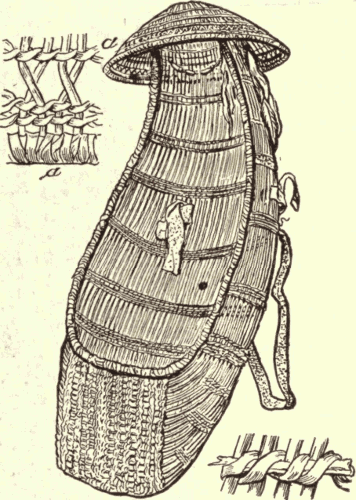

In the far north the baby-board is made of birch bark and has a protecting hood over the head; among some tribes of British Columbia, it is dug out of a single piece of wood in the form of a trough or canoe; among the Chinooks it has a head-flattening board hinged on, by which the baby's head is changed in form; one baby-board from Oregon was shaped like a great [pg 025] arrowhead, covered with buckskin, with a sort of pocket in front in which the little fellow was laced up; among some tribes in California, the cradle is made of basket work and is shaped like a great moccasin; some tribes of the southwest make the cradle of canes or slender sticks set side by side and spliced together; among some Sioux the cradle is covered completely at the sides with pretty beadwork, and two slats fixed at the edges project far beyond the upper end of the cradle.

But the baby is not always kept down on the cradle-board. Sometimes among the Sacs and Foxes he is slung in a little hammock, which [pg 026] is quickly and easily made. Two cords are stretched side by side from tree to tree. A blanket is then folded until its width is little more than the length of the baby; its ends are then folded around the cords and made to overlap [pg 027] midway between them. After the cords are up, a half a minute is more than time enough to make a hammock out of a blanket. And a more comfortable little pouch for a baby could not be found.

Among the Pueblos they have a swinging cradle. It consists of a circular or oval ring made of a flexible stick bent and tied together at the ends. Leather thongs are laced back and forth across it so as to make an open netting. The cradle is then hung from the rafters by cords. In it the baby swings.

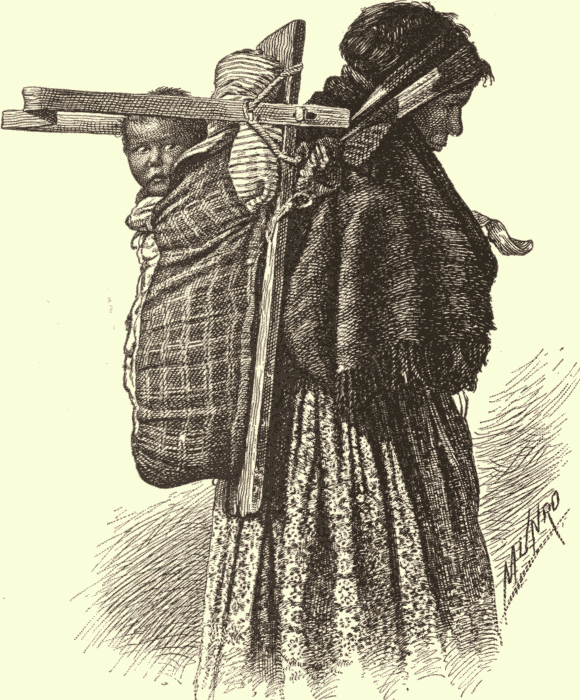

The baby who is too large for his baby-board is carried around on his mother's or sister's, or even his brother's, back. The little wriggler is laid upon the back, and then the blanket is bound around him to hold him firmly, often leaving only his head in sight, peering out above the blanket. With her baby fastened upon her back in this way the mother works in the fields or walks to town.

Among some tribes, particularly in the southern states and in Mexico, the baby strides the mother's back, and a little leg and foot hang out on either side from the blanket that holds him in place. Among some tribes in California the women use great round baskets tapering to a point below; these are carried by the help of a carrying strap passing around the forehead. During the season of the salmon fishing these baskets are used in carrying fish; at such times [pg 028] baby and fish are thrown into the basket together and carried along.

The Indian boys play many games. When I used to meet Sac and Fox boys in the spring-time, each one used to have with him little sticks made of freshly cut branches of trees. These had the bark peeled off so they would slip better. They were cut square at one end, and bluntly pointed at the other. Each boy had several of these, so marked that he would know his own. When two boys agreed to play, one held one of his sticks, which was perhaps three feet long and less than half an inch thick, between his thumb and second finger, with the forefinger against the squared end and the pointed end forward. He then sent it sliding along on the grass as far as it would go. Then the other boy took his turn, trying of course to send his farther.

The young men have a somewhat similar game, but their sticks are carefully made of hickory and have a blunt-pointed head and a long slender tail or shaft. These will skim a long way over snow when it has a crust upon it.

One gambling game is much played by big boys and young men among the Sacs and Foxes. It is called moccasin. It is a very stupid game, but the Indians are fond of it. Some moccasins are turned upside down, and one player conceals under one of them a small ball or other object. Another tries then to guess where the ball lies. [pg 029]

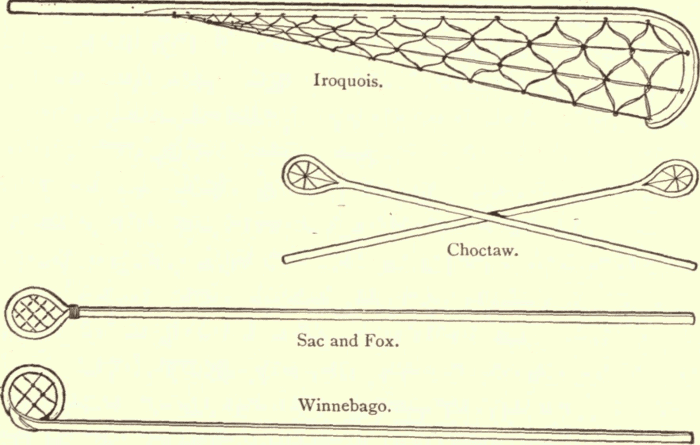

Many of the Indian tribes had some form of ball game. Sometimes all the young men of a town would take part. The game consisted in driving the ball over a goal. The players on both sides were much in earnest, and the games were very exciting. In the play a racket was used consisting of a stick frame and a netting of thongs. The shape of this racket or ball stick differed among different tribes. Sometimes one racket was used by one player, sometimes two. Among the Iroquois the game is called by the French name of lacrosse. The young men of one village often played against those of another. They used a curious long racket consisting of a curved stick with netting across the bend. The [pg 030] Choctaws, Cherokees, and other tribes near them have two rackets for each player.

Catlin tells us that in their games there would sometimes be six to eight hundred or a thousand young men engaged. He says: "I have made it an uniform rule, whilst in the Indian country, to attend every ball-play I could hear of, if I could do it by riding a distance of twenty or thirty miles; and my usual custom has been on such occasions to straddle the back of my horse and look on to the best advantage. In this way I have sat, and oftentimes reclined and almost dropped from my horse's back, with irresistible laughter at the succession of droll tricks and kicks and scuffles which ensue, in the almost superhuman struggles for the ball. Their plays generally commence at about nine o'clock, or near it, in the morning; and I have more than once balanced myself on my pony from that time till nearly sundown, without more than one minute of intermission at a time, before the game has been decided."

But these great games of ball with hundreds of players are quite past, and the sport, where still kept up, grows less and less each year.

George Catlin.—Artist and traveler. See XXII.

V. Stories Of Indians.

The Indians everywhere are fond of stories. Some of their stories are about themselves and their own deeds; others recount the past deeds of the tribe; many are about some wise and good man, who lived long ago, and who taught them how they should live and what dances and ceremonies they should perform; some are attempts to explain why things are as they are; others tell of the creation of the world.

Of these many stories some may be told at any time and anywhere, while others are sacred and must only be told to certain persons on particular occasions. Among some tribes the "old stories" must not be told in the summer when the trees are full of green leaves, for the spirits of the leaves can listen; but when winter comes, and snow lies on the ground, and the leaves have fallen, and the trees appear to be dead, then they may tell their stories about the camp-fire in safety. We can give only a few of these stories from three different tribes.

An Iroquois Story Of The Pleiades.

You all know the stars that are called the Pleiades. Sometimes, but wrongly, they are called the Little Dipper. They are a group of [pg 032] seven little stars that look as if they were quite close together.

The Iroquois tell this story about them: There were once seven little Indian boys who were great friends. Every evening they used to come to a little mound to dance and feast. They would first eat their corn and beans, and then one of their number would sit upon the mound and sing, while the others danced around the mound. One time they thought they would have a much grander feast than usual, and each agreed upon what he would bring for it. But their parents would not give them what they wanted, and the little lads met at the mound without their feast. The singer took his place and began his song, while his companions started to dance. As they danced they forgot their sorrows and "their heads and hearts grew lighter," until at last they flew up into the air. Their parents saw them as they rose, and cried out to them to return; but up and up they went until they were changed into the seven stars. Now, one of the Pleiades is dimmer than the rest, and they say that it is the little singer, who is homesick and pale because he wants to return but cannot.

A Story Of Glooskap.

The Algonkin tribes of Nova Scotia, Canada, and New England had a great many stories about a great hero named Glooskap. They believed [pg 033] he was a great magician and could do wonders. In stories about him it is common to have him strive with other magicians to see which one can do the greatest wonders and overpower the other. Glooskap always comes out ahead in these strange contests.

Usually Glooskap is good to men, but only when they are true and honest. He used to give people who visited him their wish. But if they were bad, their wish would do them far more harm than good.

One of the Glooskap stories tells of how he fought with some giant sorcerers at Saco. There was an old man who had three sons and a daughter. They were all giants and great magicians. They did many wicked things, and killed and ate every one they could get at. It happened that when he was young, Glooskap had lived in this family, but then they were not bad. When he heard of their dreadful ways he made up his mind to go and see if it was all true, and if it were so, to punish them. So he went to the house. The old man had only one eye, and the hair on one half of his head was gray. The first thing Glooskap did was to change himself so that he looked exactly like the old man; no one could tell which was which. And they sat talking together. The sons, hearing them, drew near to kill the stranger, but could not tell which was their father, so they said, "He must be a great magician, but we [pg 034] will get the better of him." So the sister giant took a whale's tail, and cooking it, offered it to the stranger. Glooskap took it. Then the eldest brother came in, and seizing the food, said, "This is too good for a beggar like you."

Glooskap said, "What is given to me is mine: I will take it." And he simply wished and it returned.

The brothers said, "Indeed he is a great magician, but we will get the better of him."

So when he was through eating, the eldest brother took up the mighty jawbone of a whale, and to show that he was strong bent it a little. But Glooskap took it and snapped it in two between his thumb and finger. And the giant brothers said again, "Indeed he is a great magician, but we will get the better of him."

Then they tested him with strong tobacco which no one but great magicians could possibly smoke. Each took a puff and inhaled it and blew the smoke out through his nose to show his strength. But Glooskap took the great pipe and filled it full, and at a single puff burnt all the tobacco to ashes and inhaled all the smoke and puffed it out through his nostrils.

When they were beaten at smoking, the giants proposed a game of ball and went out into the sandy plain by the riverside. And the ball they used was thrown upon the ground. It was really a dreadful skull, that rolled and snapped at Glooskap's heels, and if he had been a common man or [pg 035] a weak magician it would have bitten his foot off. But Glooskap laughed and broke off a tip of a tree branch for his ball and set it to rolling. And it turned into a skull ten times more dreadful than the other, and it chased the wicked giants as a lynx chases a rabbit. As they fled Glooskap stamped upon the sand with his foot, and sang a magic song. And the river rose like a mighty flood, and the bad magicians, changed into fishes, floated away in it and caused men no more trouble.

Scar-Face: A Blackfoot Story.

There was a man who had a beautiful daughter. Each of the brave and handsome and rich young men had asked her to marry him, but she had always said No, that she did not want a husband. When at last her father and mother asked her why she would not marry some one, she told them the sun had told her he loved her and that she should marry no one without his consent.

Now there was a poor young man in the village, whose name was Scar-face. He was a good-looking young man except for a dreadful scar across his face. He had always been poor, and had no relatives and no friends. One day when all the rich young men had been refused by the beautiful girl, they began to tease poor Scar-face. They said to him:—

"Why don't you ask that girl to marry you? You are so rich and handsome." [pg 036]

Scar-face did not laugh at their unkind joke, but said, "I will go."

He asked the girl, and she liked him because he was good; and she was willing to have him for her husband. So she said: "I belong to the sun. Go to him. If he says so, I will marry you."

Then Scar-face was very sad, for who could know the way to the sun? At last he went to an old woman who was kind of heart. He asked her to make him some moccasins, as he was going on a long journey. So she made him seven pairs and gave him a sack of food, and he started.

Many days he traveled, keeping his food as long as he could by eating berries and roots or some animal that he killed. At last he came to the house of a wolf.

"Where are you going?" asked the wolf.

"I seek the place where the sun lives," said Scar-face.

"I know all the prairies, the valleys, and the mountains, but I don't know the sun's home," said the wolf; "but ask the bear; he may know."

The next night the young man reached the bear's house. "I know not where he stops. I know much country, but I have never seen the lodge. Ask the badger; he is smart," said the bear.

The badger was in his hole and was rather cross at being disturbed. He did not know the sun's house, but said perhaps the wolverine would [pg 037] know. Though Scar-face searched the woods, he could not find the wolverine.

In despair he sat down to rest. He cried to the wolverine to pity him, that his moccasins were worn out and his food gone.

The wolverine appeared. "Ah, I know where he lives; to-morrow you shall see: it is beyond the great water."

The next morning the wolverine put the young man on the trail, and at last he came to a great water. Here his courage failed; he was in despair. There was no way to cross. Just then two swans appeared and asked him about himself.

When he told his story, they took him safely over. "Now," said they, as he stepped ashore, "you are close to the sun's house. Follow that trail."

Scar-face soon saw some beautiful things in the path,—a war-shirt, shield, bow, and arrow. But he did not touch them.

Soon he came upon a handsome young man whose name was Morning Star. He was the child of the sun and the moon. They became great friends.

Together they went to the house of the sun, and there Morning Star's mother was kind to Scar-face because her son told her that Scar-face had not stolen his pretty things. When the sun came home at night, the moon hid Scar-face under some skins, but the sun knew at once that some one was there. So they brought him [pg 038] forth and told him he should always be with Morning Star as his comrade. And one day he saved his friend's life from an attack of long-beaked birds down by the great water.

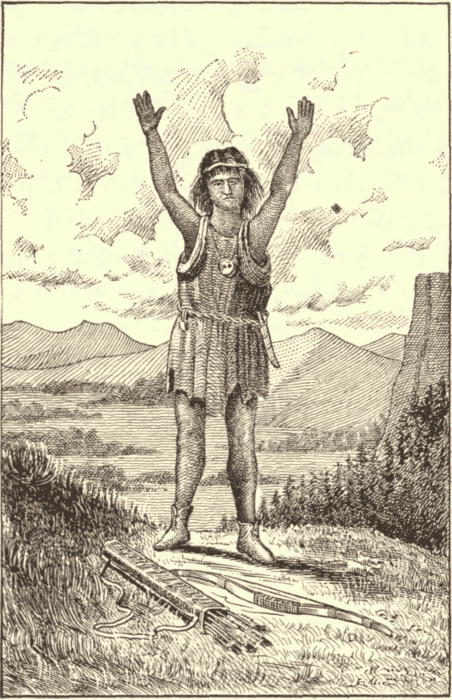

Then the sun and moon were happy over what he had done and asked what they could do for him. And Scar-face told them his story, and the sun told him he should marry his sweetheart. And he took the scar from his face as a sign to the girl. They gave him many beautiful presents, and the sun taught him many things, and how the medicine lodge should be built and how the dance should be danced, and at last Scar-face parted from them, and went home over the Milky Way, which is a bridge connecting heaven and earth.

And he sat, as is the custom of strangers coming to a town, on the hill outside the village. At last the chief sent young men to invite him to the village, and they did so. When he threw aside his blanket, all were surprised, for they knew him. But he wore rich clothing, he had a beautiful bow and arrow, and his face no longer bore the scar. And when he came into the village, he found the girl, and she knew that he had been to the sun, and she loved him, and they were married.

Charles Godfrey Leland.—Poet, prose writer, and traveler. His poems appear under the nom de plume of "Hans [pg 039] Breitmann." His Algonquin Legends of New England is important.

George Bird Grinnell.—Writer. His Pawnee Hero Stories and Folk-Tales and Blackfoot Lodge Tales are charming works. We have drawn upon him for much material, especially here and in XVI. and XX.

VI. War.

All Indians were more or less warlike; a few tribes, however, were eminent for their passion for war. Such, among eastern tribes, were the Iroquois; among southwestern tribes, the Apaches; and in Mexico, the Aztecs.

The purpose in Indian warfare was, everywhere, to inflict as much harm upon the enemy, and to receive as little as possible.

The causes of war were numerous—trespassing on tribal territory, stealing ponies, quarrels between individuals.

In their warfare stealthiness and craft were most important. Sometimes a single warrior crept silently to an unsuspecting camp that he might kill defenseless women, or little children, or sleeping warriors, and then as quietly he withdrew with his trophies.

In such approaches, it was necessary to use every help in concealing oneself. Of the Apaches it is said: "He can conceal his swart body amidst the green grass, behind brown shrubs or [pg 040] gray rocks, with so much address and judgment that any one but the experienced would pass him by without detection at the distance of three or four yards. Sometimes they will envelop themselves in a gray blanket, and by an artistic sprinkling of earth will so resemble a granite bowlder as to be passed within near range without suspicion. At others, they will cover their person with freshly gathered grass, and lying prostrate, appear as [pg 041] a natural portion of the field. Again, they will plant themselves among the yuccas, and so closely imitate their appearance as to pass for one of them."

At another time the Indian warrior would depend upon a sudden dash into the midst of the enemy, whereby he might work destruction and be away before his presence was fairly realized.

Clark tells of an unexpected assault made upon a camp by some white soldiers and Indian scouts. One of these scouts, named Three Bears, rode a horse that became unmanageable, and dashed with his rider into the very midst of the now angry and aroused enemy. Shots flew around him, and his life was in great peril. At that moment his friend, Feather-on-the-head, saw his danger. He dashed in after Three Bears. As he rode, he dodged back and forth, from side to side, in his saddle, to avoid shots. At the very center of the village, Three Bears' horse fell dead. Instantly, Feather-on-the-head, sweeping past, caught up his friend behind him on his own horse, and they were gone like a flash.

A favorite device in war was to draw the enemy into ambush. An attack would be made with a small part of the force. This would seem to make a brave assault, but would then fall back as if beaten. The enemy would press on in pursuit until some bit of woods, some little hollow, or some narrow place beneath a height was reached. Then suddenly the main body of attack, which had been carefully concealed, would rise to view on every side, and a massacre would ensue. [pg 042]

After the white man brought horses, the war expeditions were usually trips for stealing ponies. These, of course, were never common among eastern tribes; they were frequent among Plains Indians. Some man dreamed that he knew a village of hostile Indians where he could steal horses. If he were a brave and popular man, companions would promptly join him, on his announcing that he was going on an expedition. When the party was formed, the women prepared food, moccasins, and clothing. When ready, the party gathered in the medicine lodge, where they gashed themselves, took a sweat, and had prayers and charms repeated by the medicine man. Then they started. If they were to go far, at first they might travel night and day. As they neared their point of attack, they became more cautious, traveling only at night, and remaining concealed during the daylight. When they found a village or camp with horses, their care was redoubled. Waiting for night, they then approached rapidly but silently.

Each man worked by himself. Horses were quickly loosed and quietly driven away. When at a little distance from the village they gathered together, mounted the stolen animals, and fled. Once started, they pressed on as rapidly as possible.

It was the ambition of every Plains Indian to count coup. Coup is a French word, meaning a stroke or blow. It was considered an act of great [pg 043] bravery to go so near to a live enemy as to touch him with the hand, or to strike him with a short stick, or a little whip. As soon as an enemy had been shot and had fallen, three or four often would rush upon him, anxious to be the first one to touch him, and thus count coup.

There was really great danger in this, for a fallen enemy need not be badly injured, and may kill one who closely approaches him. More than this, when seriously injured and dying, a man in his last struggles is particularly dangerous. It was the ambition of every Indian youth to make coup for the first time, for thereafter he was considered brave, and greatly respected. Old men never tired of telling of the times they had made coup, and one who had thus touched dreaded enemies many times was looked upon as a mighty warrior.

Among certain tribes it was the custom to show the number of enemies killed by the wearing of war feathers. These were usually feathers of the eagle, and were cut or marked to show how many enemies had been slain. Among the Dakotas a war feather with a round spot of red upon it indicated one enemy slain; a notch in the edge showed that the throat of an enemy was cut; other peculiarities in the cut, trim, or coloration told other stories. Of course, such feathers were highly prized.

Every one has seen pictures of war bonnets made of eagle feathers. These consisted of a [pg 044] crown or band, fitting the head, from which rose a circle of upright feathers; down the back hung a long streamer, a band of cloth sometimes reaching the ground, to which other feathers were attached so as to make a great crest. As many as sixty or seventy feathers might be used in such a bonnet, and, as one eagle only supplies a dozen, the bonnet represented the killing of five or six birds. These bonnets were often really worn in war, and were believed to protect the wearer from the missiles of the enemy.

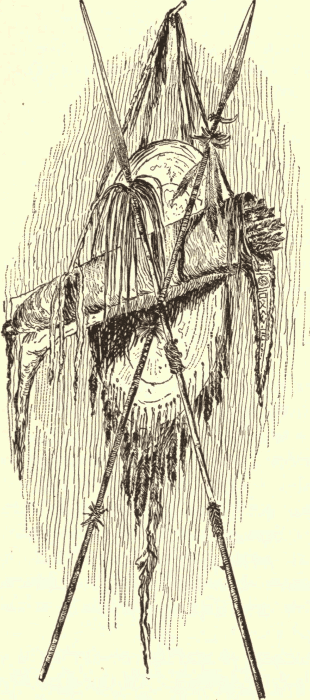

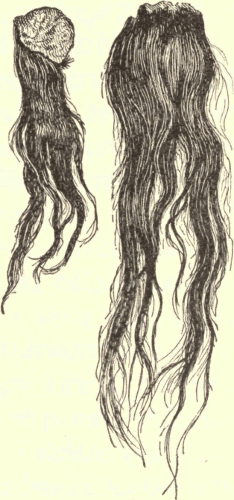

The trophy prized above all others by American Indians was the scalp. Those made in later days by the Sioux consist of a small disk of skin from the head, with the attached hair. It was cut and torn from the head of wounded or dead enemies. It was carefully cleaned and stretched on a hoop; this was mounted on a stick for carrying. The skin was painted red on the inside, and the hair arranged naturally. If the dead man was a brave wearing war feathers, these were mounted on the hoop with the scalp.

It is said that the Sioux anciently took a much larger piece from the head, as the Pueblos always did. Among the latter, the whole haired skin, including the ears, was torn from the head. At Cochiti might be seen, until lately, ancient scalps with the ears, and in these there still remained the green turquoise ornaments.

While enemies were generally slain outright, such was not always the case. When prisoners, [pg 045] one of three other fates might await them: they might be adopted by some member of the tribe, in place of a dead brother or son; they might be made to run the gauntlet as a last and desperate chance of life. This was a severe test of agility, strength, and endurance. A man, given this chance, was obliged to run between two lines of Indians, all more or less armed, who struck at him as he passed. Usually the poor wretch fell, covered with wounds, long before he reached the end of the lines; if he passed through, however, his life was spared. Lastly, prisoners might be tortured to death, and dreadful accounts exist of such tortures among Iroquois, Algonkin and others. One of the least terrible was as follows: the unfortunate prisoner was bound to the stake, and the men and women picked open the flesh all over the body with knives; splinters of pine were then driven into the wounds and set on fire. The prisoner died in dreadful agony. [pg 046]

VII. Hunting And Fishing.

To the Indian hunting and fishing were serious business. Upon the man's success depended the comfort and even the life of the household. Game was needed as food. The Indians had to learn the habits of the different animals so as to be able to capture or kill them. Boys tried early to learn how to hunt.

Clark tells of an Indian, more than eighty years old, who recalled with great delight the pleasure caused by his first exploit in hunting. "When I was eight years of age," he said, "I killed a goose with a bow and arrow and took it to my father's lodge, leaving the arrow in it. My father asked me if I had killed it, and I said, ‘Yes; my arrow is in it.’ My father examined the bird, fired off his gun, turned to an old man who was in the lodge, presented the gun to him and said, ‘Go and harangue the camp; inform them all what my boy has done.’ When I killed my first buffalo I was ten years old. My father was right close, came to me and asked if I killed it. I said I had. He called some old men who were by to come over and look at the buffalo his son had killed, gave one of them a pony, and told him to inform the camp." Such boyish successes were always the occasion of family rejoicing. [pg 047]

To the Indians of the Plains the important game was buffalo; and for buffalo two great hunts were made each year,—a summer and a winter hunt. Sometimes whole villages together went to these hunts. Few cared to stay behind, for fear of attack by hostile Indians. Provisions and valuables which were not needed on the journey were carefully buried, to be dug up again on the return. At times the people of a village went hundreds of miles on these expeditions. Baggage was carried on ponies in charge of the women. At night it took but a few minutes to make camp, and no more was necessary in the morning for breaking camp and getting on the way.

In journeying they went in single file. Scouts constantly kept a lookout for herds. When a herd was sighted, it was approached with the greatest care: everything was done according to fixed rules and under appointed leaders. When ready for the attack, the hunters drawn up in a single row approached as near as possible to the herd and waited for the signal to attack. When it was given, the whole company charged into the herd, and each did his best to kill all he could. All were on horseback, and armed with bows and arrows. They tried to get abreast of the animal and to discharge the weapon to a vital spot. One arrow was enough to kill sometimes, but usually more were necessary. A single successful hunter might kill four or five in a half hour.

After the killing a lively time ensued. The [pg 048] dead animals were skinned, cut up, and carried on ponies into camp. There the skins were pegged out to dry, the meat was cut up into strips or sheets for drying, or made up into pemmican. Every one was busy and happy in the prospect of plenty of food.

Sometimes, however, no herds could be found. Day after day passed without success. The camp was well-nigh discouraged. Then a buffalo dance was held. In this the hunters dressed themselves in the skins and horns of buffalo, and danced to the accompaniment of special music and songs.

In dancing, they imitated the movements of the buffalo, believing that thus they could compel the animals to appear. Hour after hour, even day after day, passed in such dancing until some scout hurrying in reported a herd in sight. Then the dance would abruptly cease, its object being gained.

Of course many ingenious devices were employed in hunting. Antelope were stalked; fur-bearing animals were trapped or snared. Sometimes all the animals in a considerable area were driven into a central space where they were killed, or from which they were driven between lines of stones or brush, to some point where they would fall over a cliff and be killed in the fall. Such drives used to be common in the Pueblo district. To-day deer are rarer there; so are the mountain lion and the bear. Hunts there are more likely [pg 049] nowadays to be for rabbits than for larger game. These are caught in nets, but are more frequently killed by rabbit sticks, which may be knot-ended clubs or flat, curved throwing sticks, a little like the boomerangs of Australia.

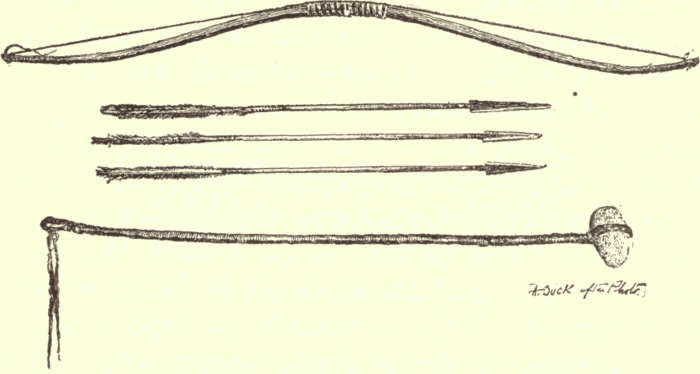

The great weapon for hunting was the bow and arrow. Indian bows ranged from frail, weak things, hardly suitable for a child, to the "strong bow" of the Sioux and Crows, which would send an arrow completely through a buffalo; the most powerful Colt's revolver—so Clark says—will not send a ball through the same animal. The Crows sometimes made beautiful bows of elk horn; such cost much labor and were highly valued. Three months' time was spent in making a single one. Arrows required much care in their making. In some tribes each man made all his arrows of precisely one length, [pg 050] different from all others. This was an aid in recognizing them. Many carried with them a measure, the exact length of their arrows so as to settle disputes. This was necessary to determine who had killed a given animal: the carcass belonged to the man whose arrow was found in it.

Among some eastern tribes, and particularly in the south, where fine canes grow near streams, the blow-gun is used. This consists of a piece of cane perhaps eight or ten feet long, which is carefully pierced from end to end and then smoothed inside. Arrows are made from slender shafts of rather heavy and hard wood. They are perhaps a foot and a half long and hardly more than a quarter or an eighth of an inch thick. They are cut square at one end and pointed at the other; around the shaft, toward the blunt end, a wrapping of thistle-down is firmly secured with thread. This surrounds perhaps three or four inches of the arrow's length, and has a diameter such as to neatly fit the bore of the blow-gun. The arrow is inserted in the tube, and a sudden puff of breath sends it speeding on its way. An animal the size of a rabbit or woodchuck may be killed with this weapon at an astonishing distance.

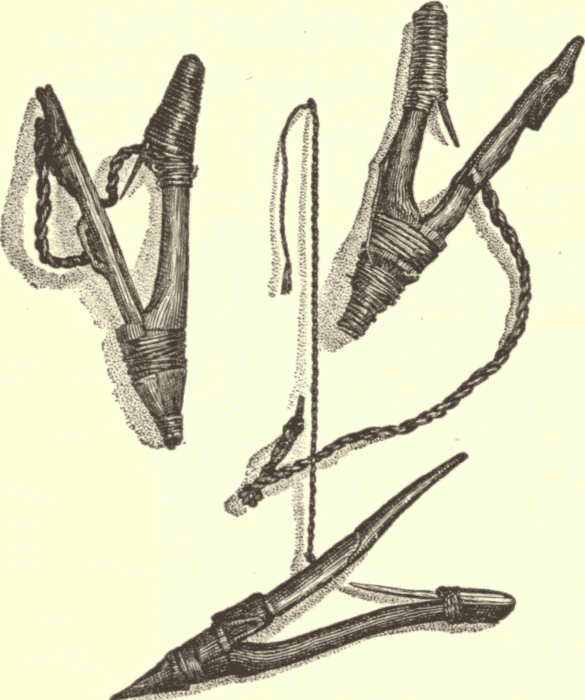

Among inland tribes, fishing was usually a matter of secondary importance. Fish pieced out the food supply rather than formed its bulk. But along some seacoasts fish is a very important food. The tribes of the Northwest Coast live [pg 051] almost entirely upon fish. The salmon is particularly important among them. These tribes have devised many kinds of lines, hooks, nets, fish-baskets, traps, and wiers. Everywhere the commonest mode of securing fish is and was by spearing.

Once I went out at night with some Indian boys of Gay Head, Martha's Vineyard, "neeskotting." These boys have a good deal of Indian blood, but they dress, talk, and act in most ways just like white boys. I think neeskotting, however, is truly Indian. "We rode down to the shore in an ox-cart, carrying lanterns with us. Each boy had a pole, at the end of which was firmly tied a cod-hook. The tide was falling, and the wind was blowing in toward shore. Walking along the beach, with lantern held in one hand so as to see the shallow water's bottom, and with the pole in the other hand ready for use, the boys watched for fish. Hake, a foot or more long, frost fish, lighter colored and more slender, and eels, are the usual prey. The hake and eels rarely come into water less than six inches deep. Frost fish, on the contrary, come [pg 052] close into shore, and on cold nights crowd out on the very beach. When a fish has been seen, a sudden stroke of the pole and a quick inpull are given to impale the prey, and drag it in to shore. It was an exciting scene. Hither and thither the boys darted, with strokes and landings, with cries of joy at success or despair at failure. Finally, with perhaps fifty hake, twenty frost fish, and one shining eel, the bottom of our cart was covered, and we turned homeward."

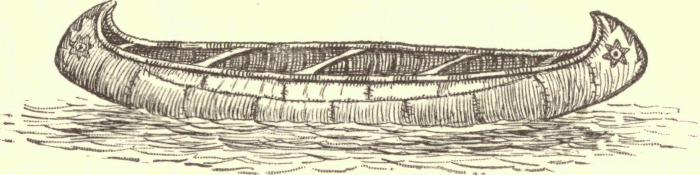

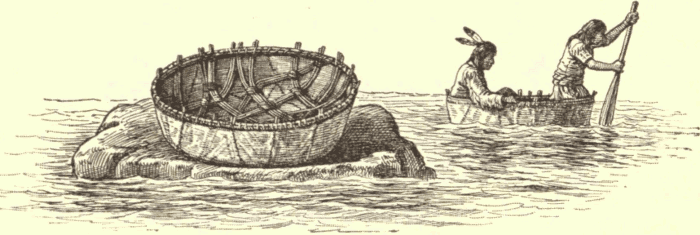

In fishing, hunting, and journeying, the woodland Indians needed some sort of water craft. They had a number of different kinds of canoes. The "dug-out," cut from a single tree trunk, is still used in many of our Southern streams; the Cherokees in their lovely North Carolina home have them. Along the Northwest Coast, magnificent war-canoes, capable of carrying fifty or sixty persons, were made from single giant logs; these canoes often had decorative bow and stern pieces carved from separate blocks. The birch-bark canoes were made over light wooden frames with [pg 053] pieces of birch bark neatly fitted, sewed, and gummed, to keep out the water. Almost all the Algonkin tribes and the Iroquois used them upon their lakes and rivers; they were light enough to be carried easily across the portages. A few tribes, the Mandans among others, had the light but awkward "bull-boat," or coracle, nearly circular, consisting of a light framework covered with skin: such were chiefly used in ferrying across rivers.

VIII. The Camp-Fire.

One of the first things after reaching camp was to build the camp-fire. Among Indians the camp-fire not only served for heat and cooking, but for light, and to scare away animal foes and bad spirits. You and I would probably have a hard time making a fire without matches. The Indian had no matches until he got them from the whites. There are two ways in which the Indians made fire. One was by striking two hard pieces of stone—such as chert or pyrites—together, which gave a spark, which was caught on tinder and blown to a flame. Of course white men used to make fire in much the same way—only they had a flint and steel. When whites first came into contact with Indians, they used the flint and steel, and it was not long before the [pg 054] Indians had secured them from the white traders. Many Indians still use the old-fashioned flint and steel. Some old Sac and Fox men always carry them in their tobacco pouch, and use them for lighting their pipes.

Another Indian method of making fire was by rubbing two pieces of wood together. It is said that this is not difficult, but one needs to know just how, in order to succeed. In the cliff ruins of the southwest two little sticks are often found together. One may be a foot or two long, and the lower end is bluntly pointed, worn smooth, and blackened as if it had been slightly burned. The other stick is of the same thickness, but may be only a few inches long; in it are several conical hollows, which are charred, smooth, and usually broken away at the edge. These two sticks were used by the "cliff-dwellers” for making fire. The second one was laid down flat on the ground; the pointed end of the other was placed in one of the holes in the lower piece, and the stick was whirled between the hands by rubbing these back and forth. While the upright stick was being whirled, it was also pressed down with some little force. By the whirling and pressure fine wood dust was ground out which gathered at the broken edge of the conical cavity. Soon, in the midst of this fine wood dust, there appeared a spark. Some dry, light stuff was at once applied to it, and it was blown into a flame.

Certainly this mode of making fire was hard [pg 055] on the hands—it must soon have raised blisters. Some tribes had learned how to grind out a spark without this disadvantage. The lower stick was as before. A little bow was taken, and its cord was wrapped about the upright stick and tightened. The two sticks were then put into position, the top of the upright being steadied with a small block held in the left hand; the bow being moved back and forth with the right hand, the upright was caused to whirl easily and rapidly. This was used among many of our tribes.

Although making it themselves, many Indians think the fire made with the bow-drill is sacred, and that it comes from heaven. Among the Aztecs of Mexico there was a curious belief and ceremony. The Aztecs counted their years in groups of fifty-two, just as we count ours by hundreds or centuries. They thought the world would come to an end at the close of one of these fifty-two year periods. Therefore, they were much disturbed when such a time approached. When the end of the cycle really came, all the fires and lights in the houses had been put out; not a spark remained anywhere. When it was night, the people went out along the great causeway to Itztapalapa, at the foot of the Hill of the Star. On the summit of this hill was a small temple. At the proper hour, determined by observing the stars, the priests cast a victim on the altar, tore out his heart as usual, and placed the lower stick of the fire-sticks upon the wound. [pg 056] The upright stick was adjusted and whirled. For a moment all were in great anxiety. The will of the gods was to be made known. If no spark appeared, the world would at once be destroyed; if there came a spark, the gods had decreed at least one cycle more of existence to the world. And when the spark appeared, how great was the joy of the people! All had carried unlighted torches in their hands, and now these were lighted with the new fire, and with songs of rejoicing the crowd hurried back to the city.

Boys know pretty well how Indians cooked their food. Most of us have roasted potatoes in the hot ashes, and broiled meat or frogs' legs over the open fire. The Indians did much the same. Pieces of meat would be spitted on sharp sticks, and set so as to hang over the fire. Clams, mussels, and other things, were baked among the hot coals or ashes. One time "Old Elsie," a Lipan woman, took a land turtle, which I brought her alive, and thrust it head first into the fire. This not only killed the turtle, but cooked it, and split open the hard shell box so that she could get at the meat inside.

Over the fireplace the Indians usually have a pot or kettle suspended in which various articles may be boiling together. The Indians invented succotash, which is a stew of corn and beans; we have borrowed the thing and the name. At the first meal I ate among the Sacs and Foxes, we all squatted on the ground, outside the house [pg 057] and near the fire, and took a tin of boiled fish off the coals. We picked up bits of the fish with our fingers, and passed the pan around for every one to have a drink of the soup.

All this is easy cooking; but how would you go to work to boil buffalo meat if you had no kettle, pot, nor pan of any kind? A great many Indian tribes knew how. When a buffalo was killed, the hide was carefully removed. A bowl-like hole was scraped out in the ground and lined with the buffalo skin, the clean side up. This made a nice basin. Water was put into this and the pieces of meat laid in. A hot fire was kindled near by, and stones were heated in it, and then dropped into the basin of water and meat. So the food was boiled. A number of tribes cooked meat in this way, but one was called by a name that means "stone-boilers"—Assinaboines.

Meat was often dried. In some districts where the air is clear and dry and the sun hot, the meat is cut into strips or sheets, and dried by hanging it on lines near the house. At other places it was dried and smoked over a fire. Where there was buffalo meat, the Indian women made pemmican, which was good. The buffalo meat was first dried as usual. The dried meat was heated through over a low fire, and then beaten with sticks or mauls to shreds. Buffalo tallow was melted and the shredded meat stirred up in it. All was then put into a bag made of buffalo skin and packed as tightly as possible; the bag was [pg 059] then fastened up and sewed tight. Sometimes the marrow-fat was also put into this pemmican, and dried berries or choke-cherries. Pemmican kept well a long time, and was such condensed food that a little of it lasted a long time. It was eaten dry or stewed up in water into a sort of soup.

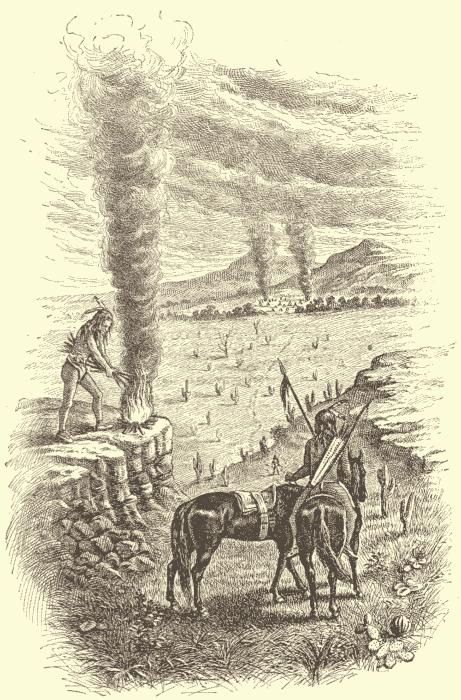

A curious use for fire among some Indians was in giving signals. A place visible from a great distance was selected. Upon it a little fire was built with fuel which gave a dense smoke. Sometimes the signal depended upon the number of fires kindled side by side. Thus when Pima Indians returned from a war-party against Apaches, they gave smoke signals if they had been successful. A single fire was built first; its one smoke column meant success. Then a number of little fires, kindled in a line side by side, indicated the number of scalps taken. Sometimes messages were given by puffs of smoke. When the fire had been kindled, a blanket was so held as to prevent the smoke rising. When a lot of smoke had been imprisoned beneath it, the blanket was suddenly raised so as to let it escape. It was then lowered, held, and raised so as to cause a new puff. These puffs of smoke rose regularly in long, egg-shaped masses, and according to their number the message to be sent varied. Such signaling by smoke puffs was common among Plains tribes. [pg 060]

IX. Sign Language On The Plains.

Every one talking with another person who speaks a different language will, in his effort to make himself understood, quite surely make some use of signs. Often the signs so used will seem naturally to express the desired idea. Once, a Tonkaway Indian in trying to tell me that all white men were untruthful, put the first two fingers of his right hand, slightly separated, near his mouth and then moved the hand downward and outward, at the same time slightly spreading the fingers. By this he meant to say that white men had two tongues, or were liars. They say one thing and mean another.

While it is natural for all people to use signs to convey meaning, the use of signs will be most frequent where it is a common thing for several people speaking different languages to come into contact. While all American Indians use some gestures, the Plains Indians, who were constantly meeting other tribes, necessarily made much use of them. In fact, a remarkable sign language had grown up among them, whereby Sioux, Crows, Assinaboines, Pani, Arapahoes, Cheyennes, Kiowas, could readily converse upon any subject.

It is not probable that the sign language was invented by any one tribe. Many writers have [pg 061] claimed that it was made by the Kiowas. Rather, it grew up of itself among the tribes because gesturing is natural to peoples everywhere.

Deaf-mutes left to themselves always use signs. These signs are of two kinds. They either picture or copy some idea, thing, or action, or they point out something. It is interesting to find that the gestures made by deaf-mutes and Indians are often the same. So true is this, that deaf-mutes and Indians quite readily understand each other's signs. Parties of Indians in Washington for business are sometimes taken to the Deaf-Mute College to see if the two—Indians and deaf-mutes—can understand each other. While they cannot understand every sign, they easily get at each other's meaning. One time a professor from a deaf-mute school, who knew little of Indians and nothing at all of Indian languages, had no difficulty while traveling through Indian country in understanding and in making himself understood by means of signs.

We will look at a few examples of Indian signs. Try and make them from the description, and see whether you think they are natural or not. The signs for animal names usually describe or picture some peculiarity of the animal.

Beaver.—Hold out the left hand, with the back up, pointing to the right and front, in front of the body, with the lower part of the arm horizontal; cross the right hand under it so that the back of the right hand is against the left palm. Then leaving the right wrist all the time against the left palm, briskly move the right hand up and down so it shall slap against the left palm. The beaver has a broad, flat tail, with which he strikes mud or water. The sign imitates this action. [pg 063]

Buffalo.—Close the hands except the forefingers; curve these; place the hands then against the sides of the head, near the top and fairly forward. These curved forefingers resemble the horns of the buffalo and so suggest that animal.

Dog.—Place the right hand, with the back up, in front of and a little lower than the left breast: the first and second fingers are extended, separated, and point to the left. The hand is then drawn several inches to the right, horizontally. I am sure you never would guess how this came to mean dog. You remember how the tent poles are dragged by ponies when camp is moved? Well, before the Indians had horses as now, the dogs used to have to drag the poles. This sign represents the dragging of the poles.

Skunk.—The skunk is a little animal, but it has rather a complicated sign. (a) The height is indicated as in the case of the badger. (b) Raise the right hand, with the back backward, a little to the right of the right shoulder; all the fingers are closed except the forefinger, which is curved; the hand is then moved forward several inches by gentle jerks. This represents the curious way in which the broad, bushy tail is carried and the movement of the animal in walking. (c) Raise right hand toward the face, with the two first fingers somewhat separated, to about the chin. Then move it upward until the nose passes between the separated finger tips. This means smell. (d) Hold both hands, closed with backs up, in front of the body, the two being at the same height. Move them down and outward, at the same time opening them. This is done rather briskly and vigorously. It means bad. Thus in the sign for skunk we give size, character of tail and movement, and bad smell.

There are of course signs for the various Indian tribes, and some of these are interesting because they usually present some striking characteristic of the tribe named.

Arapaho.—The fingers of one hand touch the breast in different parts to indicate the tattooing of that part in points.

Arikara.—often called "corn-eaters," are represented by imitating the shelling of corn, by holding the left hand still, the shelling being done with the right.

Blackfeet.—Pass the flat hand over the outer edge of the right foot from the heel to beyond the toe, as if brushing off dust.

Comanche and Shoshone.—Imitate with the hand or forefinger the crawling motion of the snake.

Flathead.—The hand is raised and placed against the forehead.

We will only give one more example. The sign for crazy is as follows:—

Slightly contract the fingers of the right hand without closing it; bring it up to and close in front of the forehead; turn the hand so that the finger tips describe a little circle.

Bad boys sometimes speak of people having wheels in their head. This Indian sign certainly seems to show that the Indian idea of craziness is about the same as the boys'.

Captain Clark wrote a book on the Indian [pg 065] sign language, in which he described great numbers of these curious signs. Lieutenant Mallery, too, made a great collection of signs and wrote a long paper about them. A third gentleman has tried to make type which shall print the sign language. He made more than eight hundred characters. With these he plans to teach the old Indians to read papers and books printed in the signs. He thinks that the Indian can take such a paper, and making the signs which he sees there pictured, he will understand the meaning of the article.

Garrick Mallery.—Soldier, ethnologist. Connected with Bureau of Ethnology from its establishment until his death. His most extended papers are: Sign Language among North American Indians, Pictographs of the North American Indians, Picture Writing of the American Indians.

Lewis Hadley.—Inventor of Indian Sign Language type.

X. Picture Writing.

The Indians did not know how to write words by means of letters. There were, however, many things which they wished to remember, and they had found out several ways in which to record these. [pg 066]

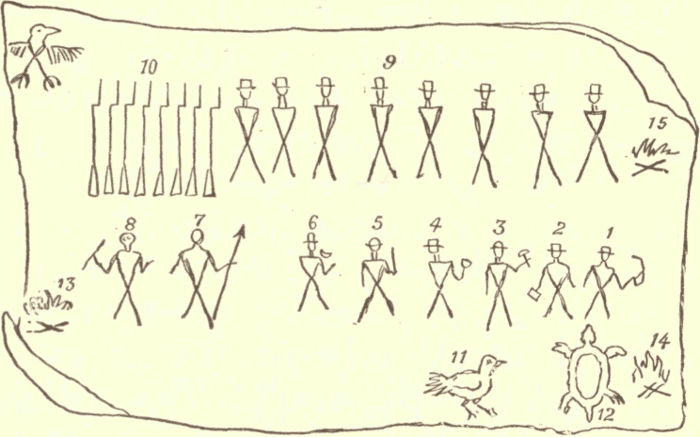

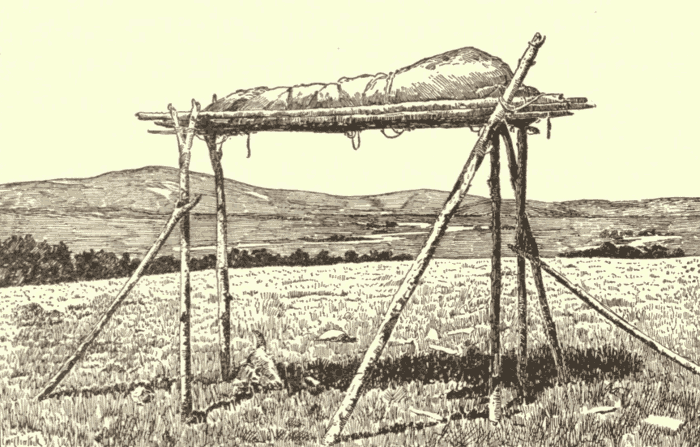

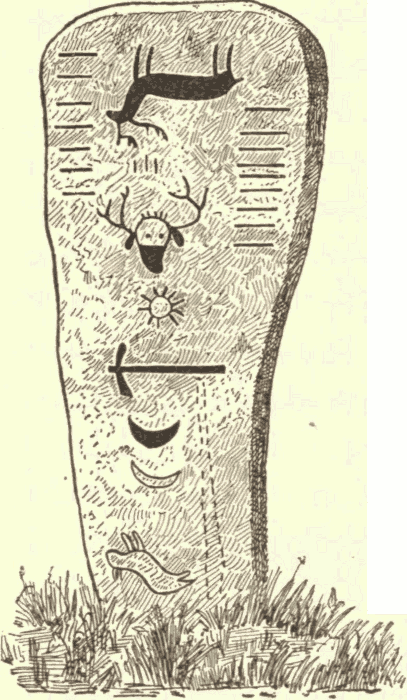

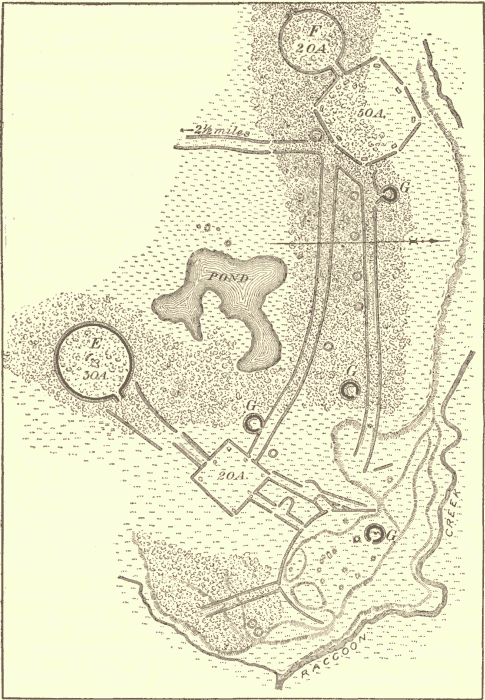

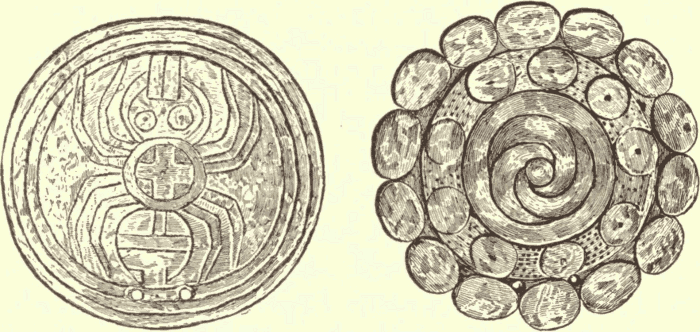

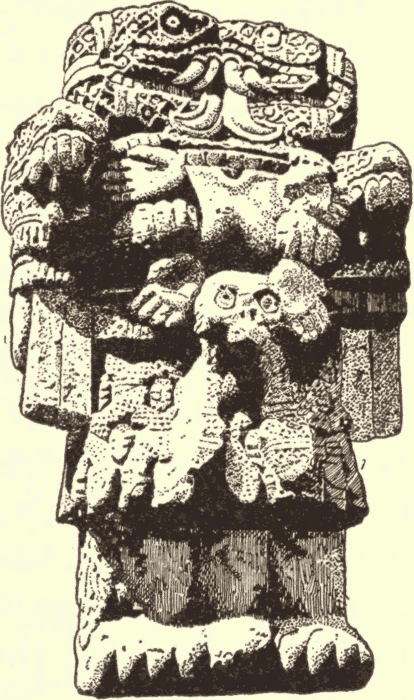

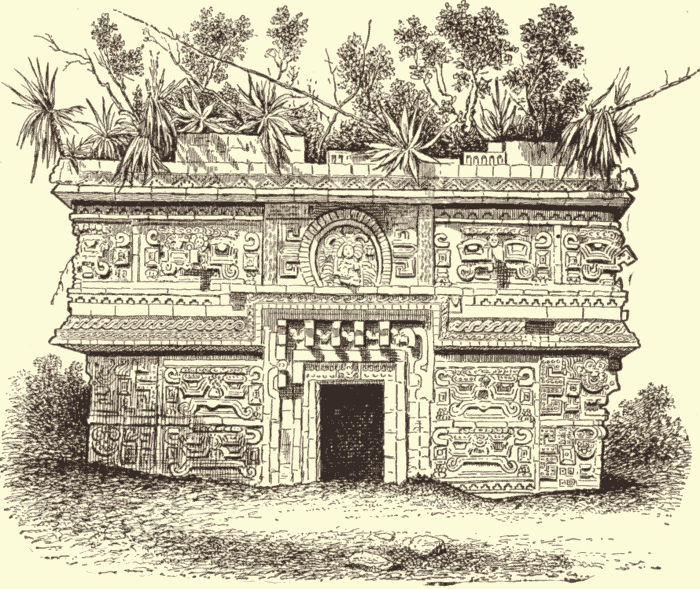

Thus among the Sacs and Foxes there is a long legend with songs telling about their great teacher, the good, wise, and kind Wisuka. It is difficult to remember exactly such long narratives, but with objects to remind the reciter of each part, it is not so hard. So the persons who are to repeat the legend have a micäm. This is a wooden box, usually kept carefully wrapped up in a piece of buckskin and tied with a leathern thong; in it are a variety of curious objects, each one of which reminds the singer or reciter of one part of the narrative. Thus he is sure not to leave out any part. In the same way mystery men among other Algonkin tribes have pieces of birch bark upon which they scratch rude pictures, each of which reminds them of the first words of the different verses in their songs. Such reminders are great helps to the memory. Among the Iroquois and some eastern Algonkins, they used, as we shall see, wampum belts to help remember the details of treaties or of important events.