THE LENAPE STONE

OR

THE INDIAN AND THE MAMMOTH

BY

H. C. MERCER

G. PI PUTNAM S SONS

The Knickerbocker Press

1885

H. C. MERCER

1885

G. P. PUTNAM S SONS

New York

PREFACE.

IN claiming an impartial examination of so extraordinay a carving as the "Lenape Stone" at the hands of archaeologists, the writer has had several difficulties to contend with.First, The fact that the carving is quite unique, it being the first aboriginal carving of the mammoth thus far claimed to have been discovered in North America.

Second, That no "scientific observer" was present at the discovery.

Third, That since its discovery the Stone has been several times cleaned, and that thereby many geological tests of its authenticity have been rendered impossible.

Fourth, That within the last few years, and particularly in Philadelphia, serious frauds have been perpetrated upon lovers of Indian relics.

These considerations may well have been sufficient to prejudice the mind of a stranger against the alleged wonderful Indian relic, yet they should in no case suffice to prevent, on the part of the archaeologists, a thorough and impartial examination of all the evidence pertaining to its discovery.

In presenting this and other evidence, the writer has [pg iv] wished only to be impartial, and to be led by the facts as they have presented themselves, and for the examination of which his opportunities have been peculiarly favorable.

In his knowledge of the neighborhood and its people (his home), an acquaintance with all the persons concerned, and very frequent visits to the Hansell Farm, nothing has yet occurred to shake his faith in the unimpeachable evidence of an honest discovery. Yet should any fresh light be brought to bear upon the subject, how ever at variance with this opinion, it will be welcomed.

The appearance in America of a carving of the hairy mammoth, presumably the work of our aborigines, if not a surprise to students of archaeology, would certainly be no less interesting than the French discoveries of some twenty years ago; while the ready connection of the work with the Indian of comparatively recent times, the appearance of human figures in the carving, and of many symbols which seem related to highly important branches of archaeological study, would awaken a more general and enthusiastic interest in the Stone, than has been felt for any other prehistoric representation of the great elephant.

A disbelief in its authenticity would leave us with an interest, not inconsiderable, in the unknown person who, after months of careful study and preparation, could have conceived and executed so remarkable a fraud.

THE LENAPE STONE.

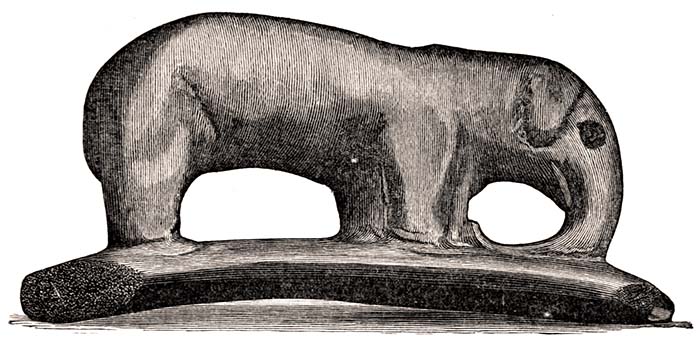

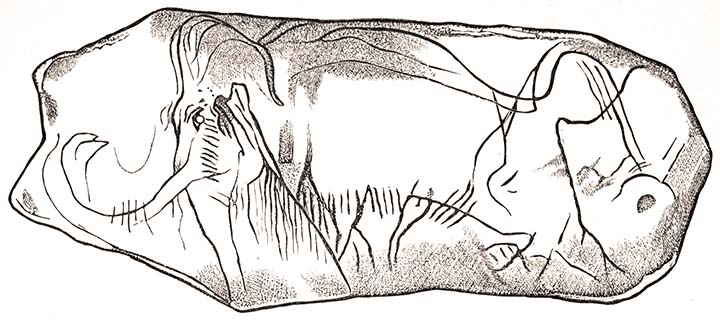

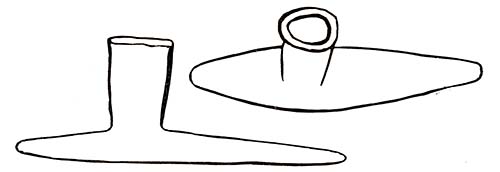

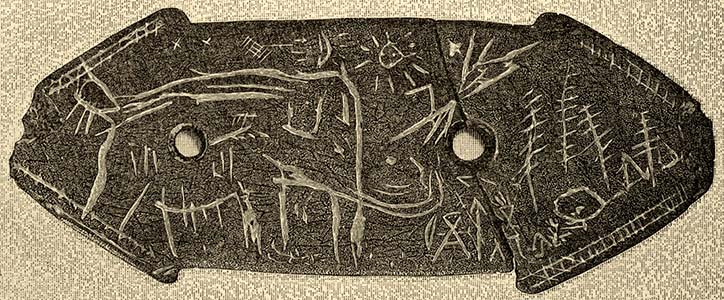

In the spring of 1872, eight years after the discovery of the famous mammoth carving in the cave of La Madeleine, Perigord, France, Barnard Hansell, a young farmer, while ploughing on his father's farm, four miles and a half east of Doylestown, Bucks County, Pennsylvania, saw, to use his own words, a "queer stone" lying on the surface of the ground, and close to the edge of the new furrow. The plough had just missed turning it under. He stopped and picked it up; it was the larger piece of the fractured "gorget stone," in fig. 1, (frontis-piece). By wetting his thumb and rubbing it he could see strange lines and a carving representing an animal like an elephant, but without troubling his boyish head much about it, he carried it several days in his pocket, and finally locked it up in his chest, where, along with his other relics, arrow-heads, spear-points, axes, and broken banner stones, thrown in from time to time as he found them on the farm, it remained until the spring of 1881, when he sold it to Mr. Henry Paxon, son of a well-known resident of the neighborhood, then a youth of nineteen, and with a fancy for collecting Indian antiquities, in whose possession [pg 2] it still remains.1 At the moment of the purchase no particular attention had been paid to the carvings, and the new owner was not certain that he had noticed the mammoth while at Hansell's house, or until a few hours later, when he had brought home his trophies and shown them to his father, who distinctly remembers calling his son's attention to the rude outline of an elephant upon the stone.

But without doubt the singular part of the story is the unexpected finding of the smaller piece of the fractured stone a few months later. After many ineffectual searches for it in the intervening years, it was picked up by Hansell while corn-husking with his brother in the same field and at the same spot where nine years before the first piece had been found. This luckily discovered fragment Hansell presented to Mr. Paxon. Several persons of the neighborhood had seen the stone at Mr. Paxon's house both before and after the discovery of the second piece, but it was not until both parts had been some months in his possession that any unusual interest was attached to it even by him.

Some time in July, 1882, Captain J. S. Bailey, of the Bucks County Historical Society, to whom the writer in preparing the present article must acknowledge his great indebtedness, and who first called serious attention to the archaeological value of the stone, made it the subject of a paper read before the Society, but since that time, [pg 3] although displayed at a county exhibition and twice shown at meetings of the Society above mentioned, this remarkable relic has remained unheard of.

This is the simple story of most great archaeological discoveries; no "man of science" was at hand to analyze the condition of the surrounding soil, or satisfy himself that a fraud had not been committed, and a hundred questions now arise as to the finder of the stone, and its present owner, its long unrecognized importance, the whereabouts of Bucks County, Pennsylvania, etc., etc. The "modern scientist" will by no means be satisfied with such evidence as would be held sufficient in a court of law, and every fraud that has been perpetrated upon the lover of Indian relics adds to the necessity of carefully examining each detail of the discovery—nothing must be believed except upon the strongest evidence.

For a full discussion of this evidence the reader is referred to the appendix.

Several circumstances seem to concur in adding to the novelty of the discovery. In the first place the carving has been made upon one of the so-called "gorget stones," than which no class of Indian relics have been more puzzling to archaeologists. Our museums are well-supplied with these mysterious perforated tablets of slate, generally resembling in size and shape the stone represented in fig. 1, and which are found in all parts of the United States. Ornaments, talismans, breastplates, or buttons, as we may choose to call them, they seem to have been the peculiar property of the [pg 4] North American Indian, without a counterpart, as far as the writer can learn, in the stone implements of other uncivilized races. They seem often to have been buried with the dead warrior and when discovered in Indian graves are generally close to the breast of the skeleton.2 Gorgets are frequently scratched and scribbled upon, and ornamental zig-zags and cross-lines, like the faint scratches plainly to be seen on the Lenape stone crossing the carvings in all directions, are not uncommon on these stones, pipes, banner stones, and other Indian implements; but picture-writings proper, such as are commonly found painted upon buffalo robes, scratched upon birch bark, or carved upon the face of cliffs or large boulders, are exceedingly rare on small stones, and the tablet in question is the only known instance, the writer believes, of a pictured gorget. The carving, when compared with the larger and more conventional Muzzinabiks or rock-writings and birch-bark records of the Indians, seems to lack much of the symbolic obscurity common to these productions of the prophets and medicine men. It doubtless belongs [pg 5] to the less hieratic class of writings, known among the Algonkins as "Kekeewin," which dealt with things generally understood by the tribe.

It is unquestionably a picture of a combat between savages and the hairy mammoth—an encounter such as our imagination has not yet connected with the ancient forests of America, and drawn as well as an Indian who had seen the great monster could have drawn it. Most of the figures seem represented according to the common conventional method of the modern Indians, yet there is certainly a seeming picturesque relation between them of which we can find no example in the few ancient Indian pictographs which have been preserved to us. We can almost fancy a foreground, a distance, and a faint chiarooscuro.

The combat we might imagine takes place on the confines of a forest, and if we may judge from an upward inclination of the foreground on the right, at the base of a hillside. The monster, angry, and with erect tail, approaches the forest, in which, through the pine trunks, are seen the wigwams of an Indian village. In the sky overhead, and as if presiding over the event, are ranged the powers of heaven: forked lightning flashes through the tree-tops, and from between a planet and the crescent moon, beyond which we seem to see a constellation (represented by a series of crossed lines) and two stars, the sun's face looks down upon the scene. Four human forms confront the monster, the first holds in his right hand a bow from [pg 6] which the arrow just discharged is sticking in the side of the enraged beast, and in his left, if it is not planted in the ground, a long lance; a second warrior with headdress of feathers stands farther to the right; and still farther, and near what may perhaps be called a rock, a third sits upon the ground apparently smoking a pipe. A fourth figure is easily distinguishable trampled under the fore feet of the mammoth.

The strong effect upon the fancy of the rude carving, as we gaze upon it, would be hard indeed to resist. Its stern naiveté and characteristic lack of aesthetic purpose bring upon the mind a haunting sense of the reality of the event it represents, and our sympathies seem genuinely awakened for the four human beings who have dared to confront the monster with their rude weapons of stone, yet whose destiny, like that of their huge antagonist, is overshadowed by the near presence of a supernatural power, seen in the great phenomena of nature which the artist has connected with the scene. Well might the appearance of the hairy mammoth have excited in the superstitious mind of the Indian hunter fancies more wild than those contained in the carving. Hardly more thrilling could have been the coming of the white men in ships, or the sound of their cannon, than the sight of one of these ungainly monsters in the shadows of a primeval forest, or the crash of his irresistible advance through the underbrush.

Silva locum et magno cedunt virgulta fragore."

[pg 7] Beckendorff, a Russian engineer, who, in 1846, saw a carcass entire, "a black, horrible, giant-like mass," floating on one of the rivers of Siberia, declared that its appearance to that of a modern Indian elephant was as "that of a coarse ugly dray-horse to an Arab steed." He also noticed a ridge of stiff hair like a mane about a foot in length and extending above the shoulders and along the back.

Its size, like that of the modern elephant, must have varied considerably. The famous St. Petersburg skeleton measures but nine feet in height, while that in the Royal Museum of Natural History in Brussels reaches eleven feet, and the animal in the carving, judging from the relative size of the figures, would have been still larger than Beckendorff's carcass, which he declares measured thirteen feet in height. Geology tells us much of the aspect, epoch, habits, and range of the mammoth; that it had appeared later than the mastodon, and somewhere in the age known as the Pliocene; that there were several species—three at least—two of which were inhabitants of America; that in North America it ranged from Behring Strait to the Gulf of Mexico, and in Europe from the extremity of Eastern Siberia as far south as Rome and the Pyrenees; that it fed upon the branches of the fir, birch, poplar, willow, etc., and was probably migratory in its habits, wandering toward grazing grounds in the north in summer, and southward in winter.

The long shaggy hair with which it was clothed, distinguishing [pg 8] it in appearance from the modern elephant and its smaller contemporary, the mastodon, was composed of three distinct suits: the longest, rough, black bristles, about eighteen inches in length; the next, a coat of finer close-set hair, fawn-colored, from nine to ten inches long; and the last, a soft, reddish wool, about five inches long, filling up the interstices between the other hair, and enabling the animal to withstand an arctic cold.

The enormous tusks measured along the curve from eleven to fifteen feet, and curved quite abruptly outward and backward.

The massive grinder, sometimes weighing seventeen pounds, was a conspicuous characteristic; the whole of its surface was not brought into use at once, but successively, new grinding-points being formed from behind as the outer and older points wore away.

Several etymologies have been given for the name "mammoth"; among others, the word "behemoth" in the Book of Job, and the Arabic word "mehemot," signifying an elephant of very large size. One of the most interesting is the Tartar word "mamma," meaning the earth, suggested by Pallas, a Russian scientist, who first gave a description of the animal. "The Tungooses and Yakoots," he says, "believed that this animal worked its way in the earth like a mole. The mammoths had retired, they say, into great caverns from which they never emerge, but wander to and fro in the galleries; [pg 9] and as they pass into one the roof of the gallery rises, and the roof of the one just vacated sinks. The moment this animal sees the light it dies, and the reason why so many carcasses have been exposed to view is because of their having been deceived by the irregular conformation of the earth's surface, thus unintentionally venturing beyond the confines of darkness."3

Mastodon and mammoth bones have been discovered in Europe from the earliest times, and a history of the remarkable theories to which they had given rise before the time of Cuvier is very interesting. By the learned of by-gone times the fossils have been mistaken for the bones of Ajax, the "body of Orestes," unicorns, the teeth of St. Christopher, and the remains of Hannibal's elephants. The middle ages have given us a whole library on the subject of a race of giants, whose remains were clearly recognized in the huge bones.

In America, in colonial times, Governor Dudley, of Massachusetts, was "perfectly of opinion" that the mastodon tooth discovered near Albany in 1705 "will agree only to a human body, for whom the flood only could prepare a funeral; and without doubt he waded as long as he could keep his head above the clouds, but must at length be confounded with all other creatures."

At what period the monster became extinct in Europe is a question to which geology gives no answer from the [pg 10] point of view of human history. The evidence rests upon the variously computed age of the beds in which the fossil bones occur. In France, for instance, it is known that the mammoth, whose bones are found in the strata underlying, and therefore older than, the Somme Valley peat, became extinct before the peat stratum, thirty feet thick, which contains no bones, had formed. It had grown, says M. Boucher de Perthes, at the rate of three inches in a hundred years; and if, as geologists say, the mammoth bones of Niagara Falls were deposited in their bed before six miles of the present river gorge were worn by the cataract out of the solid rock, they may be, according to Lyell, 31,000, or Desors, 380,000 years old.

In Siberia, whence most of our information comes, many carcasses of these huge animals have been found preserved entire in the frozen mud. When and how did they perish? Possibly, says the geologist, all at once, overwhelmed by some sudden cataclysm, which, burying the carcasses in the mud, was immediately followed by an intense cold that has lasted ever since; possibly, again, great freshets in the northern rivers, overtaking the migrating herds, swept their carcasses from warmer regions to the shores of the Polar Sea.

In Europe, the fact that the mammoth survived into the human period was proved some years ago by the discovery of human stone implements associated with mammoth bones in the river gravels of the Somme Valley, France, and in the Virgin Cave at Brixham, South [pg 11] Devon, England; but more interesting still, was the discovery of prehistoric carvings of the great elephant, sketches from nature made by the "cave-men," and found in their subterranean dwellings along the river Dordogne in France, illustrations of which will be given in the following pages.

In America, we have traces of a race of savages as old or older than the now famous river-drift and cave-men of Europe. Since the "Calaveras Man" lived, a valley, say geologists, has been metamorphosed, by the slow processes of nature, into a mountain; and the "San Joachim plummet," the "Trenton gravel-flints," and stone implements from the gold-bearing gravels of California, all speak of a race of human beings who must have lived in the time of the hairy mammoth.

But who were these people? Were they Indians? or had the Indian or his ancestor the mound-builder not yet appeared? and how many thousands or tens of thousands of years ago did they exist? These are, questions which archaeology has not yet answered.

Here, however, with the carving before us we need not go back so far, nor beyond the Indian as we know him—the fierce, roving, bauble-loving, picture-making hunter of today. A study of the wonderful outlines on the stone will lead us through a period of his history extending over many hundreds, perhaps thousands, of years before the coming of Columbus; and here we may try to read, from the few vestiges of this time that chance has preserved [pg 12] to us, fragments of his picturesque mythology, strange legends of his origin and wanderings over a forest-covered continent, and the thrilling story' of the mound-builders, and of long wars when the forest soil for centuries was a "dark and bloody ground."4

That the mammoth had survived into the time of the Indian can hardly be doubted. Early travellers had frequently seen its bones at the "Big-Bone Licks" in Kentucky, whither the huge animals had come, like the deer and buffalo of modern times, to lick the salt. The great bones often seemed hardly older than those of the modern animals with which they were mingled, and, judging from their position along the modern buffalo-trails through the forest, it seems that the latter animals had followed the ancient tracks of the mammoth to and from the licks.

Not a few of these early travellers thought it worth their while to question the Indians about the huge bones and note down their answers. Jefferson, in his "Notes on Virginia," devotes several pages to the subject. He even believes the mammoth to be still in existence in his time in some remote part of the American continent. He tells the story of a Mr. Stanley, who, "taken prisoner by the Indians near the mouth of the Tanissee," relates that "after being transferred through several tribes from one to another, he was at length carried over the mountains west of the Missouri to a river which runs westwardly; [pg 13] that these bones abounded there, and that the natives described to him the animal to which they belonged as still existing in the northern parts of their country, from which description he judged it to be an elephant."

Further, in support of his theory, he gives an Indian tradition of a great monster known as the Big Buffalo. and obtained, he says, from a Delaware chief by one of the governors of Virginia during the American Revolution. Nothing has seemed more interesting in a study of the carvings on the Lenape Stone than the remarkable similarity between this tradition of the Lenni Lenape or Delawares and the carvings on this relic, discovered in the middle of their ancient territory. The chief, as the account runs, being asked as to the bones at the Big-Bone Licks in Kentucky, says that it was a tradition handed down from his fathers that "in ancient times a herd of these tremendous animals came to the Big-Bone Licks and began a universal destruction of the bear, deer, elks, buffaloes, and other animals which had been created for the use of the Indians. That the Great Man above, looking down and seeing this, was so enraged that he seized his lightning, descended on the earth, seated himself on a neighboring mountain, on a rock on which his seat and the print of his feet are still to be seen, and hurled his bolts among them till the whole were slaughtered except the big bull, who, presenting his forehead to the shafts, shook them off as they fell; but missing one at length, it wounded him in the side, whereon, [pg 14] springing around, he bounded over the Ohio, over the Wabache, the Illinois, and finally over the great lakes, where he is still living at this day."

Making due allowance for translation, and a reasonable amount of garbling, the points of similarity between the carving and the tradition—the great man above (the sun) looking down, the lightning, and the big bull presenting his forehead to the shafts, and at length wounded in the side—are very striking; and if we compare the curious circle enclosing a dot, on the inclined foreground to the right, with the "neighboring mountain," and the footprint on the rock of the tradition, the correspondence seems again too unusual for mere coincidence. On the other hand, the tradition says nothing of warriors or wigwams, or of planets, moon, and stars, yet these differences may naturally be accounted for if we suppose the stone older than the tradition, and that in the latter the local and matter-of-fact elements of time, place, and human agency would have been the first to fade away as time went on. But this is not the only Indian tradition of a great monster—presumably the mammoth—which has been preserved to us.

The element of divine wrath, common to monster myths among barbarous peoples, again occurs in a Wyandot version of the same tradition, taken down from a band of Iroquois and Wyandots by Colonel G. Croghan, at the Salt Licks in Kentucky in 1748, and given in Winterbotham's "History of the United States," vol. iii., page 139. [pg 15] The head chief, says the writer, having been flattered with presents of tobacco, paint, ammunition, etc., on being asked about the large bones, related the ancient tradition of his people as follows: "That the red man, placed on this island by the Great Spirit, had been exceedingly happy for ages, but foolish young people forgetting his rules became ill-tempered and wicked, in consequence of which the Great Spirit created the Great Buffalo, the bones of which we now see before us. These made war upon the human species alone, and destroyed all but a few, who repented and promised the Great Spirit to live according to his laws if he would restrain the devouring enemy; whereupon he sent lightning and thunder, and destroyed the whole race in this spot, two excepted, a male and female, whom he shut up in yonder mountain, ready to let loose again should occasion require."

David Cusic, the Tuscarora Indian, in his history of the Iroquois, among other instances, speaks of the Big Quisquis,5 a terrible monster who invaded at an early time the Indian settlements by Lake Ontario, and was at length driven back by the warriors from several villages after a severe engagement; and of the Big Elk, another great beast, who invaded the towns with fury and was at length killed in a great fight; and Elias Johnson, the Tuscarora chief, in his "History of the Six Nations," speaks of another monster that appeared at an early period in the history of his people, "which they called Oyahguaharh, supposed to [pg 16] be some great mammoth who was furious against men, and destroyed the lives of many Indian hunters, but who was at length killed after a long and severe contest."

Another instance of a terrible monster desolating the country of a certain tribe "with thunder and fire" appears in a collection of Wyandot traditions published by one William Walker, an Indian agent, in 1823; and again the great beast appears in the song tradition of the "Father of Oxen," from Canada, and in a monster tradition from Louisiana, both spoken of by Fabri, a French ofificer, in a letter to Buffon from America in 1748.

"The Reliquae Aquitanicae," published by Lartet and Christy, page 60, quotes a letter from British America of Robert Brown to Professor Rupert Jones, which speaks of a tradition common to several widely separated tribes in the Northwest, of lacustrine habitations built by their ancestors to protect themselves against an animal who ravaged the country a long time ago.

Hardly less remarkable in its description of the animal than any of the others is, perhaps, the Great Elk tradition as mentioned by Charlevoix in his "History of New France."

"There is current among these barbarians," says the author, "a pleasant-enough tradition of a Great Elk, beside whom all others seem like ants. He has, they say, legs so high that eight feet of snow does not embarrass him, his skin is proof against all sorts of weapons, and he has a sort of arm which comes out of his shoulder and which he uses as we do ours." [pg 17] Whatever we may have previously thought of these legends, their evidence now combined with that of the carving is irresistible. Nothing but the mammoth itself, surviving into comparatively recent times and encountered by the Indians, could suffice to account for the carving, and we can no longer suppose that the size and unusual appearance of the mammoth bones seen by the Indians in Kentucky could alone have originated the traditions.

In the carving, we have the most interesting mammoth picture in existence; not a mere drawing of the animal itself, but a picture of primitive life, in which the mammoth takes a conspicuous part in the actions and thoughts of man,—a carving made with a bone or flint instrument upon a tablet of slate at least four hundred years ago,—the hairy elephant, drawn in unmistakable outline, and attacked by human beings,—a battle-scene which thrills our imagination, and the importance of which the ancient draughtsman magnifies by the introduction of the symbols of his religion, the sun, moon, and stars, and the lightning alone powerful to overthrow the great enemy.

All is evidently the work of the Indian; so would he rudely carve trees, the pine with its straight-spreading arms, like a modern telegraph pole; his forest wigwam, a simple triangle; the sun, with human face, and a halo; and the moon, a crescent; the stars were small crosses, and diverging lines were the rays of light that traversed the sky from the great luminaries. Men were triangles with their sides produced, and three dots in the head for [pg 18] eyes, nose, and mouth; here the minute forms standing their ground before the great beast, are warriors, with feathers in their hair, and bows and lances in their hands. The chief figure, the great buffalo, or the great elk of Charlevoix, armed with a proboscis, as the Indians may well have named the mammoth, is assailed, as in the Jefferson tradition, by lightning.

Between such a monster, however inoffensive in its habits, and the Indian hunter, there could be no peace; his size and terrific appearance were enough for the superstitious fancy of the red man, and as he browses harmlessly near the village he is attacked; then his rage transforms him into the fierce enemy and destroyer of mankind remembered in the traditions. As naively represented in the carving, he tramples men to a pulp under his feet with the ungovernable fury of a modern elephant, and overturns whole villages of fragile wigwams, while his anger perhaps vents itself in loud bellowings; arrows and spears only annoy him; he must be destroyed by the lightnings of the Great Spirit to whom the medicine men pray for help.

A remarkable story, alleged in support of the coexistence of the Indian, and the mammoth's great contemporary the mastodon, regarded by most scientists with distrust, though defended by some, was that of Dr. Albert Koch, a collector of curiosities, who in 1839 disinterred the skeleton of a mastodon in a clay bed near the Bourboise River, Gasconade County, Missouri. Associated with [pg 19] the bones Koch claimed to have discovered, in the presence of a number of witnesses, a layer of wood-ashes, numerous fragments of rock, "some arrow-heads, a stone spear-point, and several stone axes," evidencing he claimed, that the huge animal had met its untimely end at the hands of savages, who, armed with rude weapons of stone and boulders brought from the bed of the neighboring river, had attacked it, while helplessly mired in the soft clay, and finally effected its destruction by fire.

Koch also published with his statement and in connection with another skeleton, that of the Mastodon giganteus discovered by him in Benton County, Missouri, a tradition of the Osage Indians, in whose former territory the bones were found, and which he says led him to the discovery. It states, says Koch, "that there was a time when the Indians paddled their canoes over the now extensive prairies of Missouri and encamped or hunted on the bluffs. That at a certain period many large and monstrous animals came from the eastward along and up the Mississippi and Missouri rivers, upon which the animals that had previously occupied the country became very angry, and at last so enraged and infuriated by reason of these intrusions, that the red man durst not venture out to hunt any more, and was consequently reduced to great distress. At this time a large number of these huge monsters assembled here, when a terrible battle ensued, in which many on both sides were killed, and the remnant resumed their march toward the setting sun. Near the bluffs which are at [pg 20] present known by the name of the Rocky Ridge one of the greatest of these battles was fought. Immediately after the battle the Indians gathered together many of the slaughtered animals and offered them up on the spot as a burnt sacrifice to the Great Spirit. The remainder were buried by the Great Spirit himself, in the Pomme de Terre River, which from this time took the name of the Big-Bone River, as well as the Osage, of which the Pomme de Terre is a branch. From this time the Indians brought their yearly sacrifice to this place, and offered it up to the Great Spirit, as a thank-offering for their great deliverance, and more latterly, they have offered their sacrifice on the table rock above mentioned (a curious rock near the spot of the discovery), which was held in great veneration and considered holy ground."

There is considerable variety of opinion of late, and especially among persons familiar with the Indians, as to the value of the information furnished by their traditions; and certainly among Indians to-day the separation of their pre-Columbian from their later traditions, and their traditions proper from the extravagant relations so readily dealt forth by them extempore, is no easy matter. Much stress is laid on the absence of a tradition of De Soto; yet, as Schoolcraft remarks, the Delawares and Mohicans had in his time one of Hudson, the Chippeways of Cartier, and the Iroquois one of a wreck on a sea-coast, and the extinction of an infant colony, probably Jamestown.

Interest in the American elephant has of late been considerably [pg 21] increased by the appearance of several supposed representations of the animal among the relics of our aborigines, drawings of which, and of the so-called elephant trunks, and head-dresses from the architecture of Mexico and Central America, are given in the following pages.

[pg 22] Not one of these outlines is unmistakable, and all lack the characteristic tusks of the mammoth.

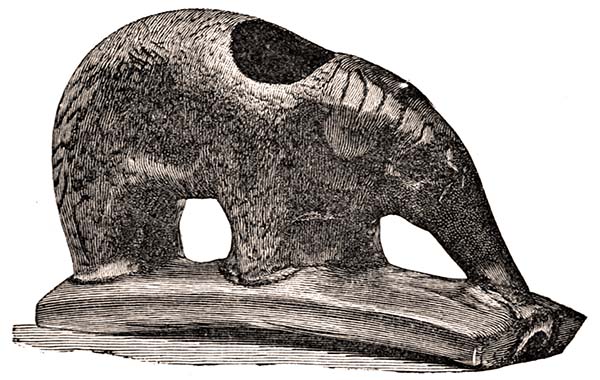

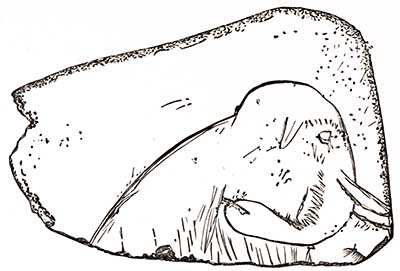

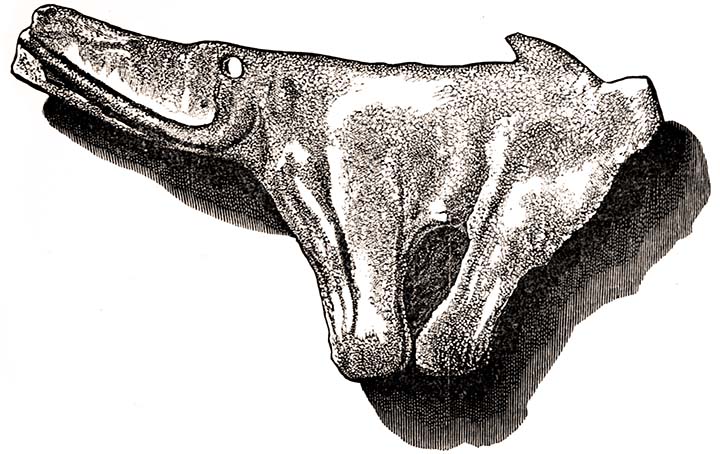

Figures 2 and 3, the now famous "elephant pipes," the authenticity of which is doubted, however, in the last report of the Bureau of Ethnology, came to light in Louisa County, Iowa. The former, discovered in 1872 or 1873, was found, it is said, on the surface by a farmer while planting corn; and the latter, more interesting from the scratches upon it evidently intended to represent hair, was taken from a mound near an old bed of the Mississippi by the Rev. Dr. Blumer and others on March 2, 1880. The material of the two pipes, which apparently have been much greased and smoked, is the same—a light- colored sandstone.

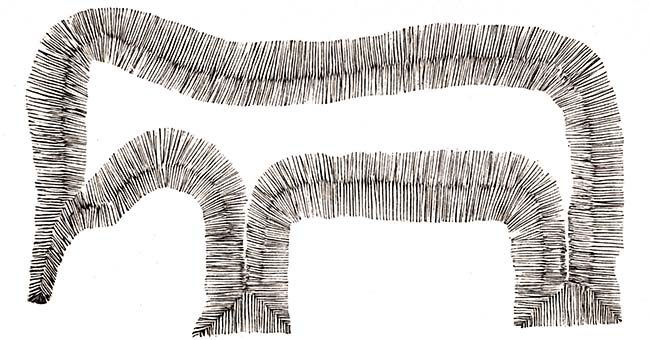

The next of the elephant documents is the so-called elephant mound of Grant County, Wisconsin, (fig. 4). It was described by Mr. Jared Warner, of Patch Grove, Wisconsin, on page 416 of the "Smithsonian Report for 1872," when public attention was first generally called to it. The effigy, 135 feet long, 60 feet broad, and but 5 feet high, is situated on the east bank of the Mississippi, just below the mouth of the Wisconsin, and, says Mr. Warner, has been known in the neighborhood of Patch Grove for twenty-five years as the "elephant mound." Like the elephant pipes, however, it lacks the characteristic tusks, and sceptics claim that its original shape has been too much modified by many years of cultivation to render judgments concerning it admissible.

But to return to the carving, a somewhat novel feature in it, and one which has been objected to as casting a doubt upon its authenticity, is the spear between the two upright human figures on the right. Large flint spear-points, so-called, are found abundantly in the Eastern States, and within the last hundred years instances of the use of the spear by the Indians in hunting and fishing are common; no one doubts, as we learn, for instance, in Tanner's narrative, that the Indians speared salmon in the Eastern rivers, or, as Catlin shows, used steel-pointed lances in their Western buffalo hunts. Yet the early writers, in their descriptions of aboriginal implements, have been supposed to make no mention of the spear, and there has been some controversy among archaeologists as to whether it can be classed among Indian prehistoric weapons of warfare or the chase.

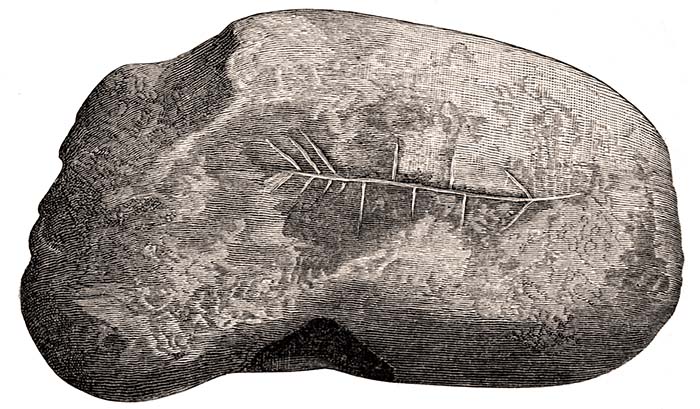

[pg 24] Dr. Abbott, who, in his "Prehistoric Industry," has given a wood-cut of the curious egg-shaped stone found at Lake Winnipissiogee, and upon which there are several carvings of spears, quotes in the same work, by way of the nearest approach to an allusion to the spear among the early writers, a description from Josselyn of an elk-hunt among the early Massachusetts Indians, in which the writer describes a lance made of a staff a yard and a half long and pointed with fish-bone. But a passage in Bernal Diaz del Castillo ("Historia verdadera de la Conquista de la nueva Espana," Madrid, 1638), kindly pointed out to the writer by Dr. Rau, seems to furnish conclusive evidence on the subject. Bernal Diaz, among several intances in his works, speaks (chapter vi.) of an attack upon the Spaniards in Florida by Indians "armed with immense-sized bows, sharp arrows, and spears, among which some were shaped like swords" ("y lanzas y unas a manera de espadas").

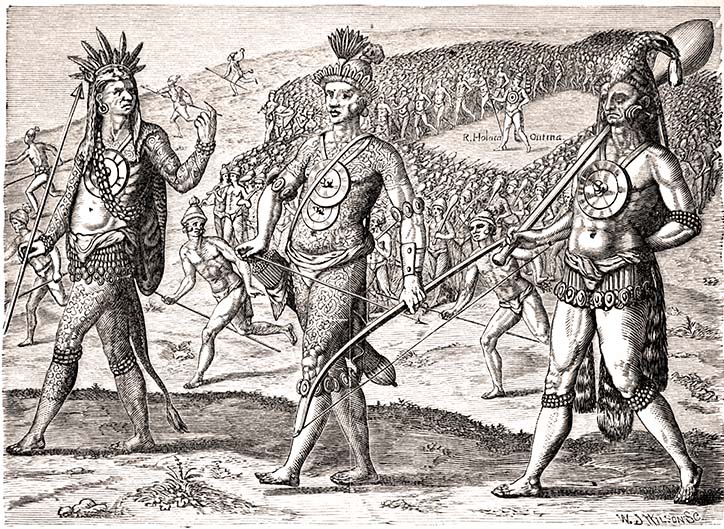

Furthermore there is fig. 5 (plate xiv. from De Bry's "Brevis Narratio," published in Latin in Frankfort-on-the-Main in 1591), representing Indians holding spears, for which likewise the writer is indebted to Dr. Rau. It was drawn from life by one Jacques Le Moyne, a French artist, in 1564. He had come to Florida with the French Admiral Laudonniere, and having been left by the expedition for some months at a fort upon the St. John's River, frequently made sketching expeditions among the neighboring tribes. Many similar drawings by him of warriors armed with spears are to be found among the numerous illustrations in De Bry.

Fig. 5. Picture of North American Indians carrying spears, drawn From life by Jacques Le Moyne, in 1564.

[pg 26] Passing over the mysterious animal on one of the Davenport tablets, sometimes taken for a mammoth, and the pictograph on a boulder near the Gila River seen by Colonel W. H. Emory in 1846 in a military reconnaissance,6 and which, he says, "may with some stretch of the imagination be supposed to be a mastodon," we come to the supposed traces of the elephant noticed by numerous writers in the mural paintings and architecture of Mexico and Central America.

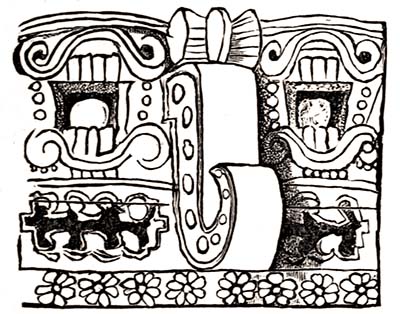

Figures 6 and 7, reduced from Catherwood's "Atlas" to Stephens' "Yucatan," are fair specimens of the remarkable architectural ornaments from Central America known as elephant trunks, and which, placed between two eyes and a mouth-like cavity, seem at first, as Waldeck and other travellers have remarked, to bear a striking resemblance to the trunk of a proboscidean.

[pg 27] Figure 6 is from the gateway of the great Teocallis at Uxmal, and 7 from that of the Casa de las Monjos at Uxmal; as in the case of all the other "elephant trunks," however, they offer no suggestion of the prominent tusks of the American elephant, and, as Dr. F. W. Putnam maintains, should perhaps be looked upon as grotesque representations of the human race, of which the so-called trunk forms the nose.

Far more striking among the so-called traces of the elephant in North America are the priests' head-dresses from Mexico and Yucatan.

|

| Fig. 8. Elephant Head-dress (Palenque). |

|

| Fig. 9. Elephant Head-dress (Mexico). |

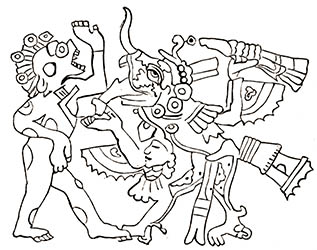

Figure 9, the no less fantastic Mexican head-dress, is from the Vues des Cordilleras, plate xv. As to it, Humboldt says: "I would not have had this hideous scene engraved, were it not for the remarkable and apparently [pg 28] not accidental resemblance of the priest's head-dress to the Hindoo Ganesa, or elephant-headed god of wisdom. It seems hardly possible to suppose that a tapir's snout could have suggested the trunk in the head-dress, and we are almost left to infer either that the people of Atzlan had received some notice of the elephant from Asia, or that their traditions reached back to the time of the American elephant."

It is interesting to compare the Lenape Stone with the mammoth carvings of the cave-men of Europe, of which we here give the series. None of these outlines equal the Lenape drawing in realistic spirit except, perhaps (fig. 10) the most remarkable of them all, the celebrated La Madeleine carving. It is engraved upon mammoth ivory and was discovered in 1864 in the cave of La Madeleine, Perigord, France, by M. Louis Lartet. It was broken into [pg 30] five fragments, and like the carving on the Lenape Stone, which it singularly resembles in general position, and in

the indecisive drawing of the back and tail, unmistakably represents the mammoth. The mammoth scratching his side (fig. 11), and the very indistinct head (fig. 12), carved [pg 31] on opposite sides of a bone plate, are from the Edouard Lartet collection. M. Louis Lartet, brother of the former, in his description of the drawings in the "Matériaux pour l'histoire primitive de l'homme," vol. ix., p. 33, thinks that "the primitive artist to whom these rude but sufficiently faithful representations are due, and who changed his. mind several times when sketching, had, without doubt, the living model before his eyes, and was disturbed in his work by the movements of the animal."

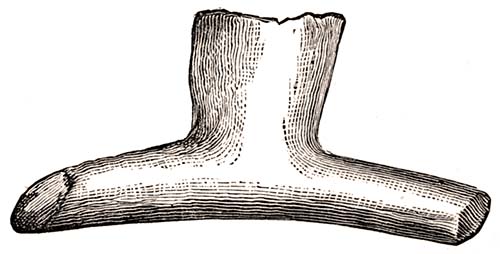

Figure 13, is the mammoth dagger-hilt carved in deer horn, in the collection of M. Peccadeau de l'Isle. It was discovered in the rock shelter of Bruniquel (Tame et Garonne), France. Here, to avoid breakage probably, the [pg 32] muzzle has been greatly exaggerated and the shape of the trunk and position of the tusks have been considerably departed from.

The least interesting specimen perhaps in the French collection is (fig. 14) the very indistinct elephant's head, minus the tusks, discovered by the Marquis de Vibraye in the cave of Laugerie Basse, Dordogne, France. Another so-called prehistoric representation of the mammoth, though resembling that animal only in the trunk-like prolongation of its muzzle, is (fig. 15) a more modern bronze specimen from Siberia. The writer of the description in the "Matériaux," vol. iv., p. 197, prefers to consider it a fantastic cat, tiger, or lion.

PART II.

Let us picture to ourselves, as it occurred in ancient times, and when his customs and traditions were as yet uncontaminated by civilization, one of the great religious feasts of the Indian—a dance, in honor, perhaps, of the sun, or pipe of peace, or of the green corn.A wildly picturesque scene rises before us, as we read the descriptions of writers who have witnessed these ceremonies in later days; such a scene, as—in the language of Catlin: "not all the years allotted to mortal man could in the least deface or obliterate from the memory."

The tribe is assembled in the Indian village, or upon a bare hill-top, or perhaps in a lonely spot in the forest; a great bonfire burns in their midst, around which many mysterious rites have been performed. The rain perhaps was to be called down from heaven, sickness averted, evil spirits to be exorcised and driven away, or the deer or moose to be led in a state of charmed fatuity into the midst of the camp. With wild noises and gestures the warriors have danced around the fire, waving corn-stalks, or fiercely brandishing their weapons of war; the odor of burning tobacco or roasting dog's flesh fills the air, and the forest re-echoes with the cawings of the crow, the [pg 35] "gobble" of the wild turkey, or the growl of the bear, exactly imitated by the dancers. With a truthfulness born of their intense sympathy for nature, the moving figures mimic the spring of the panther or wild-cat, the start of the deer, and the sinuous motion of the snake.

At length a figure, half man half animal, approaches— the prophet or medicine-man. Nothing can be more strange than his appearance; his dress is hung with the skins of snakes, frogs, and bats, and adorned with the beaks, tails, and toes of birds, and the hoofs of the deer and antelope, — a diabolical embodiment of animal monstrosity.

All is now quiet, and from his medicine bag, made of the skin of the racoon, polecat, or bat, beautifully decorated, and lined with moss and fine grass, he produces a scroll of birch bark, a tablet of wood, or a stone, engraved with mystic characters. Holding the tablet in his hands, as his eye falls upon the carved devices a low sound, rising into [pg 36] a song or chant, now only interrupted by the crackling of the fire, issues from under the hideous bear's-mask which hides his head. Each picture suggests to his mind some event of the far past, carefully treasured in the traditional lore of his tribe.7 His song, rising and falling in strange inflections, and preserving a sort of rhythm, now tells of the creation of the world, a deluge, the origin of his people, and their primitive struggles with the forces of nature; now images of primeval giants and demigods rise before the minds of the assembled tribe, his hearers, of Manabozho the great hare, of Tarentya-wagon holder of the heavens, of Hiawatha, and Nana-bush, and of "Stonish Giants," and "Flying Heads"; now he tells of the passage of great waters and mountains, of treeless plains, and forests, now of long wars with human enemies, and of the final coming of the whites. The squatting figures listen in motionless silence, as the song proceeds through its many verses, each the theme of a particular event. At last it ceases, and the pictured scroll or tablet, formula of its spell, restored to its place in the medicine pouch, remains hidden from the eyes of the tribe until its reappearance upon some similar occasion.

Such is the song-chronicle of the Indian's history; and such songs are known to have been carefully preserved and sung by many if not all of the Eastern tribes.

Such was the national song-legend of the Creeks and Choctaws, narrating in considerable detail their traditional [pg 37] origin and early migration from the West. It was read to the English by the Creek chief, Chekillè, at Savan- nah, in 1775, "and was written in red and black characters on the skin of a young buffalo." This pictured skin, with an English translation, was sent to London, and there, in a frame in the Georgia office, at Westminister, was kept for many years as a curiosity; it was finally lost, but the translation has been recently brought to light by Dr. D. G. Brinton, of Philadelphia.

Such, too, was the national song of the Cherokees, sung by them at their annual green-corn dance. Portions of it which tell of an early migration from the head-waters of the Monongahela, and of the great mound at Grave Creek which the Cherokees claim to have built, are given by Haywood in his "History of Tennessee." They were related to the author from memory by an old Indian trader who had heard the song. Mr. Chamberlain, at present missionary among the Cherokees, states that Guess or Sequoyah, a half-breed Cherokee, since dead, had invented the Cherokee alphabet of eighty-two letters, for the express purpose of perpetuating this chronicle of his nation, and had recorded it in the new characters, but these interesting manuscripts, which after his death were unfortunately mislaid, have thus far escaped discovery.

The Blackfeet, too, have a singular historical song sung on stated occasions; and the Shawnees, now situated in the northeast corner of the Indian territory, have a [pg 38] national legend, described in one of the late Indian reports as a "weird song sung in a rising melancholy strain"; it is sung at one of their great annual feasts, but as yet the double-barrelled shotgun or the "handsomest blanket in Philadelphia," offered by Dr. Brinton for a translation, have not served to break the reserve of the Indians familiar with the particular dialect in which it is sung, and who say that its revelation would bring misfortune upon the tribe.

The historical records of the Ojibways, says Ka-ge-ga-gah-bowh, or George Copway, their native historian, were written in Indian hieroglyphics upon "slate-rock, copper, lead, and the bark of birch trees," and kept in three secret underground depositories near the head-waters of Lake Superior, where, being disinterred and examined every fifteen years by a committee of chiefs, the dimmed and decaying pictographs were replaced by facsimiles.

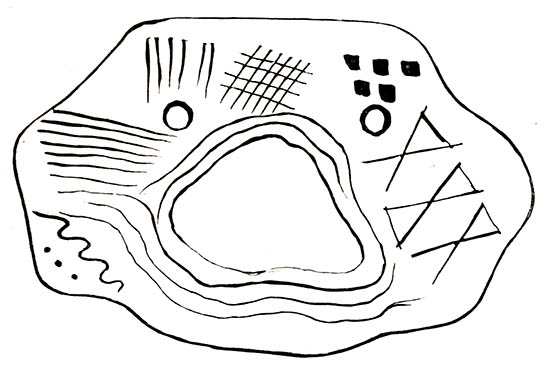

It seems highly probable, in fact, that the solemn songs above, as well as most of the important historical narratives of the Indian tribes, have been repeatedly and variously recorded in eye-catching pictures of men, animals, and natural objects, intended to refresh or jog the memory of the singer or speaker, in his lengthy recitations to the assembled tribe. And such a pictured song-chart, or reference-table we may perhaps consider the carving on the reverse of the Lenape stone (fig. 16), which, should it be, as we have supposed, a production of the [pg 39] Lenni Lenape, would not unnaturally refer to the well-known historical legend of that ancient people.

This tradition of the Delawares, more interesting and suggestive probably than any of these long-overlooked records of ancient North America, has once at least, been recorded by Indians in pictographic symbols; fortunately it has been preserved to us in full, and we can compare it with the carving on the reverse of the Lenape stone (fig. 16), which we may suppose suggested to the mind of the Indian singer versed in the art of picture-writing some at least of the events remembered in his tradition.

Two versions of this wonderful Indian chronicle have been rescued from oblivion. The first, far less complete than the other, was collected from the Indians themselves by the Moravian missionary Heckewelder, about 1800. It reads as follows: "The Lenni Lenape (according to the traditions handed down to them by their ancestors) resided many hundred years ago in a very distant country, in the western part of the American continent. For some reason which I do not find accounted for, they determined on migrating to the eastward, and accordingly set out together in a body. After a very long journey, and many nights' encampments by the way, they at length arrived at the Namaesi Sipu, or River of Fish (from namaes, a fish, and sipu, a river)."

One of the first figures that catches our eye on looking at the carvings is the unmistakable outline of a fish, (a), just beneath the waving lines; (b) representing water [pg 40] at the left of the stone. The tradition goes on to say that at this river the Delawares "fell in with the Mengwe (Iroquois, or five nations), who had likewise emigrated from a distant country, and had struck upon this river somewhat higher up. Their object was the same with that of the Delawares; they were proceeding on to the eastward until they should find a country that pleased them. The spies which the Lenape had sent forward for the purpose of reconnoitring, had long before their arrival discovered that the country east of the Mississippi was inhabited by a very powerful nation, who had many large towns built on the great rivers flowing through their land. Those people (as I was told) called themselves Talligeu or Talligewi. Colonel John Gibson, however, a gentleman who has a thorough knowledge of the Indians, and speaks several of their languages, is of opinion that they were not called Talligewi, but Alligewi, and it would seem that he is right, from the traces of their name, which still remain in the country, the Allegheny river and mountains having indubitably been named after them. The Delawares still call the former Alligewi Sipu, the River of the Alligewi."

"Many wonderful things are told of this famous people. They are said to have been remarkably tall and stout, and there is a tradition that there were giants among them, people of a much larger size than the tallest of the Lenape. It is related that they had built to themselves regular fortifications or intrenchments, from whence they [pg 41] would sally out, but were generally repulsed.8 * * * When the Lenape arrived on the banks of the Mississippi, they sent a message to the Alligewi to request permission to settle themselves in their neighborhood. This was refused them, but they obtained leave to pass through the country and seek a settlement farther to the eastward."

This agreement, that the Lenape should cross in peace, might have been symbolized in the Muzzinabiks (rock writings) and historical song records of any tribe, by the figure of the pipe (c) on the left of the stone, just above the water, and opposite the fish.

"They accordingly began to cross the Namaesi Sipu," continues the account, "when the Alligewi, seeing that their numbers were so very great, and in fact they consisted of many thousands, made a furious attack on those who had crossed, threatening them all with destruction if they dared to persist in coming over to their side of the river. Fired at the treachery of these people, and the great loss of men they had sustained, and besides, not being prepared for a conflict, the Lenape consulted on what was to be done—whether to retreat in the best manner they could, or try their strength, and let the enemy see they were not cowards, but men, and too high-minded [pg 42] to suffer themselves to be driven off before they had made a trial of their strength, and were convinced that the enemy was too powerful for them. The Mengwe, who had hitherto been satisfied with being spectators from a distance, offered to join them on condition that, after conquering the country, they should be entitled to share it with them. Their proposal was accepted, and the resolution was taken by the two nations to conquer or die. Having thus united their forces, the Lenape and Mengwe declared war against the Alligewi, and great battles were fought, in which many warriors fell on both sides."

This ancient alliance may have been symbolized to the mind of the Delaware by the figures of the hawk (c), beneath which is seen (f) perhaps a wampum belt, and of the turtle (d) in the central part of the stone, and set in divisions formed by one intersecting and four diverging lines. Devices of the "great Thunder-bird, whose eyes were fire and glance lightning, and the motion of whose wings filled the air with thunder," and of the "great turtle, upon whose back the mother of the human race had been received from heaven," were common in the mystic songs of the medas or priests, and their particular significations in these incantations might have been almost endless when we consider that to the initiated Meda or Josakeed (prophet) the same sign calls up quite different ideas, as the theme of the writer varies from war to love, or from the chase to medicine, or prophecy. If, however, we refer the subject of the carving to history, the hawk and turtle may well be viewed as the tokens or heraldic [pg 43] badges of the chief actors in the story9 (the Lenape and Mengwe).

As clan badges, both symbols were in common use among most of the Indian tribes. The turtle clan, says Heckewelder, was the governing family in any nation, and among the Delawares claimed an ascendency over the wolf and turkey families on account of its superior antiquity and relationship to "the great turtle, the Atlas of their mythology, who bore the great island—the earth—upon its back."

The hawk totem, which of course the Delawares might have applied to any people they chose, irrespective of its real emblem, occurred among the Hurons, and in both the Seneca and Cayuga tribes of the Iroquois confederacy; also among the Ojibways, Pottowatamies, Miamis, Abenakis, Sacs, and Foxes, and in many other tribes.

The account goes on to say that "the enemy fortified their large towns and erected fortifications, especially on large rivers and near lakes, where they were successively attacked and sometimes stormed by the allies. An engagement took place, in which hundreds fell, who were afterwards buried in holes or laid together in heaps and covered over with earth. No quarter was given, so that the Alligewi, at last, finding that their destruction was inevitable if they persisted in their obstinacy, abandoned the country to the conquerors and fled down the Mississippi River, from whence they never returned. The war [pg 44] which was carried on by this nation lasted many years, during which the Lenape lost a great number of their warriors, while the Mengwe would always hang back in the rear, leaving them to face the enemy."

In this description of a superior race of Indians, conquered after a most desperate resistance, and whose memory still survives, in the great mountain chain to which they have given a name, we find a key to the often-spokcn-of mystery of the mound-builders and their sudden disappearance.

The story of their long death-struggle and final overthrow by a horde of savage invaders, as here given in the formal style of Heckewelder, seems somewhat colored by his well-known partiality for the Delawares. It is confirmed, as we shall see, by the evidence of other Indian traditions and the study of their language, which seems to show that this people,—the Alligewi or mound-builders— fleeing down the Mississippi, were received and adopted by the Choctaws and Cherokees, themselves in comparatively recent times a mound-building people, and who thus have become in part their descendants.

A suggestion of these long and bloody wars, in which the Lenape did most of the fighting, may be seen in the figure of the tomahawk (g) just below the turtle,10 and of [pg 45] the mound-builders themselves perhaps, in the singular group of figures above the water on the left, i. e., the outline of a mountain or mound on which a series of numerical marks are faintly seen, a tablet inscribed with ten dots, two diagonally intersecting lines, and five parallel marks or points.

" In the end," continues the account, "the conquerors divided the country between themselves," as the wigwams (h and i) above each totem might denote. "The Mengwe made choice of the lands in the vicinity of the great lakes" and on their tributary streams, again suggested, perhaps, by the snow-shoe (j) "and the Lenape took possession of the country to the south. For a long period of time—some say many hundred years—the two nations resided peacefully in this country and increased very fast. Some of their most enterprising huntsmen and warriors crossed the great swamps, and falling on streams running to the eastward, followed them down to the great Bay River (Susquehanna), and thence into the bay itself, which we call Chesapeak." As they pursued their travels, partly by land and partly by water, in this primitive reconnaissance of the great wilderness now our homes, journeying sometimes near and at other times on the "great salt-water lake" (the sea), they finally discovered the river which we call the Delaware.

"Thence exploring still eastward," continues the account, "they discovered the Scheyichbi country, now named New Jersey, and at length arrived at another great stream— [pg 46] that which we call the Hudson or North River. Satisfied with what they had seen, they (or some of them), after a long absence, returned to their nation and reported the discoveries they had made. They described the country they had discovered as abounding in game and various kinds of fruits, and the rivers and bays with fish, tortoises, etc., together with abundance of water-fowl, and no enemy to be dreaded. They considered the event as a fortunate one for them, and concluding this to be the country destined for them by the Great Spirit, they began to emigrate thither, as yet but in small bodies, so as not to be straitened for want of provisions by the way, some even laying by for a whole year. At last they settled on the four great rivers (which we call Delaware, Hudson, Susquehanna, and Potomac), making the Delaware, to which they gave the name of 'Lenapewihittuck,' (the river or stream of the Lenape), the centre of their possessions."

Here the ancient portion of the chronicle and its parallelism with the figures on the stone seems to end, the remainder being devoted to long wars with the Mengwe, relations with the whites, and the more modern events of the history of the tribe in the east.

The other figures upon the stone—the star (k), the calumet (l), the deer (m), the curve crossed by three oblique lines (n), probably a war canoe, and the fish-like figure (o) at the end of the stone—are hardly suggested by the narrative, yet may refer to further details of the passage of the Alleghenies, and the exploration and settlement [pg 47] of the country to the east, along the great rivers and by the sea-coast.

Far more interesting than Heckewelder's account, is a full version of the great national song of the Lenape as they sung it in their own language, with an English translation, and with all the pictographic devices used to jog the memory of the singer. He may well have needed them, as the whole song consists of two hundred and two verses. It was first published in 1836 by the eccentric French-American philosopher, Rafinesque, in an extravagant work by him entitled "The American Nations," and is known as the Wallum Olum (literally, painted sticks), or pictographic traditions of the Lenni Lenape. It contains the Delaware account of the creation, a deluge, the early migrations and entire history of the tribe, and one hundred and eighty-four mnemonic symbols painted upon tablets of wood. "It was obtained" says Rafinesque, "about 1822,—the symbols from a Dr. Ward of Indiana, who had received them as a reward for a medical cure from the Delawares, at Wahapani or White River, in 1820, and the verses from another individual."

Mr. E. G. Squier, who considered the internal evidence furnished by the songs sufficiently strong to settle their authenticity, submitted the manuscript copy of the songs and pictographs in the hand of Rafinesque, who it appears had never owned the original "painted sticks," to George Copway, the Chippewa chief, who unhesitatingly, he says, pronounced it authentic. This manuscript, together with [pg 48] the pictographs, of which Rafinesque had published none, and Squier but forty, was considered hopelessly lost until its fortunate discovery a few weeks ago by Dr. Brinton, by whom it will shortly be published with a new translation.

Passing over its account of the creation and deluge, the narrative goes on to describe the passage by the Lenape of a large body of water on the ice (Behring's Straits, says Rafinesque), and their settlement at a place called Shinaki, or the "Land of Firs."

After many generations of chiefs, continues the fourth song, during which time they were continually engaged in wars with "Snakes" (enemies), they wander from the fir land to the south and east, pass over a hollow mountain Oligonunk (Oregon, according to Rafinesque), and at last "find food" at "Shililaking, the plains of the Buffalo Land." Here they tarry and build towns and raise corn on the great meadows of the Wisawana (Yellow River). But after many wars with "Snakes," "northern enemies," and "father snakes," of which we can see a suggestion in the eel-like form (p) on the stone, they again resume their migration towards the "sun-rising," and finally reach the shores of the Messussipu,11 or Great River, "which divides the land." The accompanying pictograph for verse 49, [pg 49] descriptive of the Great River, quite unlike the figure upon the stone, is here given from the original drawing by Rafinesque, kindly furnished the writer by Dr. Brinton (fig. 17). The narrative, of which we give the English translation by Rafinesque, omitting the Delaware version, continues in the original as follows:

49. The Great River (Messussipu) divided the land, and being tired, they tarried there.

|

| Fig 17. |

51. Followed Chitanitis (Strong-friend), who longed for the rich east-land.

52. Some went to the east, but the Tallegwi killed a portion.

53. Then all of one mind exclaimed: War, war!

54. The Talamatan (not of themselves) and the Nitilowan all go united (to the war).

55. Kinehepend (Sharp-looking) was their leader, and they went over the river.

56. And they took all that was there, and despoiled and slew the Tallegwi.

57. Piniokhasuwi (Stirring-about) was next chief, and then the Tallegwi were much too strong.

58. Teuchekensit (Open-path) followed, and many towns were given up to him.

59. Paganchihilla was chief, and the Tallegwi all went southward.

[pg 50] 60. Hattanwulaton (the Possessor) was sakima, and all the people were pleased.

61. South of the lakes they settled their council-fire, and north of the lakes were their friends the Talamatan (Hurons?).

Nothing could be more interesting to the lover of American archaeology than a study of this song—with the single exception perhaps of the Lenape stone, the most remarkable Indian document in existence. The latter part of the story here given, is even less suggestive than the preceding portions, which we have been obliged to omit.

The generations of chiefs, which it recites in order, seem to include thousands of years, and as we read its account of a creation and a deluge, of the passage of a great water upon the ice, and an arrival at a "Land of Firs," we almost pardon the extravagant speculations of Rafinesque, to which it gave rise.

Both versions of the account tell the same story, yet there is one striking difference between them. In the Heckewelder version the allies of the Lenape are spoken of as "Mengwi " (Iroquois, Mingoes); in the Wallum Olum as "Talamatan" (Hurons, called Delamattenos by the Delawares); but the variance is reconciled when we consider that in ancient times, as their language and traditions prove, the Hurons and Iroquois were one closely allied nation, constituting one family or linguistic stock.

We may doubt, however, whether the great river [pg 51] crossed in the migration—"Namaesi Sipu" (Fish River) in Heckewelder, and "Messussipu" in the Wallum Olum— referred to the Mississippi.

The Huron-Iroquois will tell us, when questioned, that at an early period, and while the families were still united, his people, coming originally from the northeast of Canada, migrated to the southward, and had not come from the west across the Mississippi; he too has traditions of crossing a river and attacking a race of mound-builders, but the river of his account was crossed to the southward, and lay on the north of the mound-builders' country. The Iroquois tradition is given in a famous passage, supposed to refer to the mound-builders, in the account of David Cusic, a native Iroquois, of the Tuscarora clan, who wrote a history of his tribe. We give it here in the original, uncorrected form, as published by Schoolcraft.

Referring to an early age of monsters, demi-gods, giants, and horned serpents, when the Hurons and Iroquois were as yet but one people, and they and other tribes, "the northern nations," possessed the banks of the great lakes, "where there were plenty of beavers," but "where the hunters were often opposed by the big Snakes," Cusic goes on to say that "on one occasion the northern nations formed a confederacy, and seated a great council-fire on the river St. Lawrence. Perhaps about 2,200 years before the Columbus discovered the America, the northern nations appointed a prince, and immediately repaired to the south and visited the Great Emperor, who resided at [pg 52] the Golden City, a capital of the vast Empire. After a time the Emperor built many forts throughout his dominions, and almost penetrated the Lake Erie. This produced an excitement; the people on the north felt that they would soon be deprived of the country on the south side of the great lakes. They determined to defend their country against any infringement of foreign people; long, bloody wars ensued, which lasted about one hundred years. The people of the north were too skilful in the use of bows and arrows, and could endure hardships which proved fatal to a foreign people; at last the northern nations gained the conquest, and all the towns and forts were totally destroyed, and left them in the heap of ruins."

It has been supposed that the upper St. Lawrence or Detroit River, streams noticed by the Indians as abounding in fish, was the "Fish River" of the Heckewelder tradition. Here, as we have seen according to information collected from the Lenni Lenape, desperate battles had taken place with the Allegwi, hundreds of whom were slain and buried under mounds in that vicinity.12

Other considerations, too, induce us to suppose that the Lenape and Huron-Iroquois invasion came from the northward and not from the west. If we study the shape and position of the mounds themselves along the southern shore of the great lakes, we find that they present often the appearance of fortifications erected against the advance [pg 53] of an enemy from the north, and suddenly abandoned after a long struggle. Also the scattered implements and half-removed blocks of ore found in the prehistoric copper mines on the south shore of Lake Superior, seemed to indicate their hasty desertion by the miners upon the sudden inroad of an enemy from that direction. Again, the works of the mound-builders, though at some points insignificant and hardly perceptible, extend considerably west of the Mississippi, and probably would have been encountered by the advancing Lenape before reaching that river, and had it been the stream meant it would not have been spoken of as the boundary of the mound-builders' empire.13

Messusipu is derived, says Squier, from the Algonkin words Messu, Messi, or Michi (great), and Sipu (river).

The name Mississippi is of Algonkin origin, and has the same etymology, —it means "great river." Among the Algonkin tribes living to the north and along the eastern shore of the Mississippi, the Sauks called it Mechasapo, the Menomonees Mecha-sepua, the Kicapoos Meche-sepe, the Chippeways Meze-zebe, and the Ottawas Missis-sepi; Mecha, Mecke, Meze, Missis, meaning "great," and sapo, sepua, sepe, zebe, and sepi, "river." (Wisconsin Hist. Col., ix., 301.)

The Lenape word Messusipu must therefore refer to the Mississippi. Yet we may suppose that Rafinesque had written the word by mistake in his copy of the Wallum Olum, a supposition which gains strength from the fact that Messusipu plainly appears in his manuscript to have been changed to Namasipi. Had he been comparing his copy with the original "painted sticks" or some other Indian authority not mentioned? or did he merely borrow the word Namasipi from Heckewelder? Again we may suppose the word Messusipu to have been an indefinite term applied by the Lenape to more than one of the great streams crossed by them in their migrations.

|

| Fig 18. |

There is still another song—the sixth—continuing the chronicle and recounting the melancholy story of the Lenape's contact with the whites, and final westward journey to Ohio, where the records were obtained. A narrative of sufferings and hard wrongs, whose recital by the Indian had caused Heckewelder, as he said, "to feel ashamed that he was a white man.".

The symbols appended to the songs, and among which the forms of the rectangle and circle frequently occur, end with the fifth song; they appear very arbitrary, and it is certainly disappointing to find that they bear no resemblance [pg 55] to the carvings upon the Lenape stone, likewise, as we have supposed, productions of the Lenni Lenape and dealing with the same subject. Yet we need not be surprised when we consider the varied and often arbitrary methods of Indian picture-writing.

In comparing the carvings on the reverse of the Lenape stone with the Lenape and Huron-Iroquois traditions of their early migration and struggle with the mound-builders, we have spoken only of probabilities. Possibly these carvings may refer to the incantations of the prophets and doctors, to songs for "medicine hunting," or charms against evil spirits, and not to the history of the tribe, as recounted in the Wallum Olum and the narratives of Heckewelder and Cusic. Possibly, too, the modern Indians who have seen the carvings may have entirely mistaken their subject, as similar signs are used in quite different kinds of their picture-writing. Yet if we view the chief feature of the Lenape stone—the mammoth picture—as an example of muzzinabik or historical picture-writing, an attempt to explain the carvings on the reverse of the stone as specimens of the same class of writings does not seem extravagant. Viewed in the light of these legends, and compared with the fragments of ancient Indian history which chance has preserved to us, the carvings upon the Lenape stone vividly impress upon our minds the reality of that dark period of our continent's past, antecedent to the first coming of the white man, separated from us by but a few centuries, yet [pg 56] where the boundary line between history and geology becomes indistinct, when for hundreds, perhaps thousands, of years the Indian lived alone on the "great island," and while those deep-rooted peculiarities of his character, which civilization has failed to eradicate, were slowly growing out of his wilderness life.

The ancient presence of the Lenape is often remembered in the heart of his former dominions. Along the shores of the beautiful river, whose transatlantic name, applied also to his tribe, he resented, the arrow-head and tomahawk, everywhere found upon sites of ancient camps and fishing-grounds, tell of the long centuries of his possession. His memory lingers in the name and poetry of our Indian summer; and in that most delightful of autumnal seasons, when a warm wind blowing from the abode of the Great Spirit stirs the fields of ripened maize, we may see, where first the Indian's fancy must have seen it, a suggestion of his head-dress of feathers in the graceful motion of the corn-stalks. He is immortalized in richly melodious names of rivers, streams, and mountains, and his memory is forever recalled in the yearly growth of that noblest of American plants, the Indian corn.

In concluding here our view of the less distinct though not improbable reference of the carvings on the reverse of the Lenape stone to the ancient historical traditions of the Delawares, a brief review of the subject of the foregoing pages may not be out of place.

We have seen that the stone was found at a spot [pg 57] situated in the ancient territory of the Delawares, and where many articles of undoubted Indian workmanship have been found,—among them two carved stones,14—that similar aboriginal carvings of the hairy mammoth have been discovered in Europe, and that a race of men, relics of whom have been found on the Delaware river and in California, and who may or may not have been the ancestors of the modern Indian, have existed in North America at the time of the mammoth. Moreover, that as yet nothing is definitely known as to the antiquity of the Indians' occupancy of our continent, and that there is no geological evidence to prove that the mammoth did not survive in America to a comparatively recent period. We have seen further that the Indians in several of their traditions attribute the mammoth bones seen by them on the Ohio to a great monster who was destroyed by lightning, and that there is a similarity too strong to be accidental between the Lenape tradition of the great Buffalo and the carving on the stone; finally, we may see perhaps a reference in the carvings on the reverse of the stone to the early Delaware traditions of their migration to the eastward and wars with the mound-builders, as detailed in Heckewelder's account, the "Wallum Olum," and David Cusic's history.

APPENDIX.

STATEMENT OF BERNARD Z. HANSELL.

On the writer's second visit to Hansell, the latter was at his father's farm. He stated that the photographs shown him were representations of the stone, and said that he considered that he had been cheated. He had had no idea of the stone's value, and declared that it was a "mean trick," the purchase of all his relics—the stone included—for $2.50. When it was explained to him that Mr. Paxon, the purchaser, had been as ignorant as he in the matter at the time, he seemed satisfied.On the third visit, February 10th, Hansell said:

I am sure that I found the large piece first, in the spring of 1872 (the year after my father bought the place—1871), and while "ploughing for oats" in the "corner" field, and near the corner where the by-road joins the Durham road—the roots of the last year's corn crop had shortly before been harrowed out. It was in April. When I saw it, it was lying on the top of the ground, a little to one side of the furrow. I stopped and picked it up; it seemed like "something different" from what I had ever found before. It was dirty—dirt stuck to the stone; by rubbing, I could see lines—"queer marks" over it. (When I afterward saw it at Mr. Paxon's, the latter had "cleaned it.")

[pg 62] I am certain I saw an animal like an elephant on it before Mr. Paxon saw the stone. I carried it around a day or two in my pocket, and then put it in a box along with the other things; and whatever arrow-heads and other relics I found, I would put into the same box. The same day, I planted a cornstalk into the ground to mark the place—a shower might wash out something else, I thought. I left the corn-stalk until the oats harvest, and then threw a stone there, but I soon came to know the place by heart. The box with the relics I kept locked up in my trunk, and I took care to keep it locked,— there were so many boys about. In the meantime, I was married. I showed the relics and stone to my wife, but she would not remember the elephant on the stone. I might have showed it to father, or might not, I am not sure. He would not remember. In the same field, I and others on the place found arrow-heads, coins (English and American pennies), and a part of a tomahawk or banner stone (sold to Mr. Paxon). I did not find any thing else in that field, but "gorget Stones" without inscriptions, and round stone balls, with incisions on sides, were found near by.

In the spring of 1881, Mr. Paxon asked me whether I had any Indian relics. I said that I had. I told him I would be at home on Sunday, and he came the next Sunday afternoon—about May or June, as nearly as I can recollect,—1881. I brought out the box of relics, and told him that I would sell him the perfect arrow-heads for ten cents, and the broken ones for five cents apiece. I had a broken tomahawk and a piece of another, and I laid them and the stone aside, and said I thought I would keep them. But he did not take much interest in the rest, and said he wanted all the relics. He did not look much at the arrow-heads, but he picked up the stone and turned it around, and wet his thumb and rubbed it. He did not say any thing about the stone. I did not much want to sell him the stone, for I never saw any thing like it before. [pg 63] But he said he would take all the relics or none for $2.50. So I let him have them. At the same time he asked me whether I had not the other piece; perhaps I had, he said, and did not know it. I told him that I had not.

About a month after that time, he came by on foot and asked me whether I had found any thing more? I said that I had not. "If you do," he said, "keep it and give me the first chance."

I always had the other piece in my mind, and when I went in the field I used to look for it. I would walk around the spot in a circle, for I thought some one might have picked it up and then thrown it away again.

After we had cut the corn in the field, and as I went in to husk, I happened to pass near the place—I always remember the place,—I was thinking of the other piece, and was hardly in the field before I picked it up. I noticed the marks and the shape, and saw at once that it was the missing piece. It had notches around the edges. I put it in my pocket and laid it in the drawer. My wife never saw it. It was the little piece. I was married then and in my own house, and there was nobody about the house, so I did not lock it up. This was in the fall—after the exhibition at Doylestown (October), in 1881. When I went down to Mr. Paxon's father's. Squire Paxon's, to pay my tax, on the 9th of November, 1881, I took this piece along. Young Mr. Paxon was not at home, but I waited till he came back. I said I had something "pretty nice" for him, and showed him the missing piece. He thought when he saw it that I would make him pay pretty dear for it, but I told him that I would give it to him. I had not rubbed or cleaned it. He put the pieces together and said "that is the missing piece." He took me up to his room and gave me some minerals. I advised him to glue the pieces together with "hickory cement." I had some of this cement at home, and offered to give it to him.