WRITINGS

OF

CALEB ATWATER

COLUMBUS

PUBLISHED BY THE AUTHOR

PRINTED BY SCOTT AND WRIGHT

1833

Entered according to act of Congress, in the year 1833,

by Caleb Atwater, In the Clerk's Office of the District Court of Ohio.

TO

GENERAL DUNCAN McARTHUR,

LATE GOVERNOR

OF

THE STATE OF OHIO,

THIS VOLUME IS DEDICATED,

AS

A SMALL MARK

OF

THE REGARD, RESPECT AND ESTEEM

OF

THE AUTHOR.

[pg 5]

PREFACE

In presenting the following pages to the public, were I assured that none would peruse them but the citizens of Ohio, no prefatory remarks would be necessary. The work itself, as its title imports, consists of such of my writings as I wish to acknowledge as such. My other essays, on a great variety of subjects, I have seen fit to leave out of the collection, for various reasons. Some articles were written in haste, to answer some temporary purpose;—to oblige a friend, to amuse myself, or, worse than all, to promote the interests of some party, or partisan, who showed me afterwards how unworthy they, or he could be, of my friendship or regard. On other subjects, further reflection or more information, has changed my views, either in part or wholly. Other essays may be retouched, added to, or retrenched from, and thus be presented again to the public, should my life be prolonged, or my friends desire it.My remarks on the ancient works in the Western States, originally appeared in the first volume of the American Antiquarian Society, in the year 1820. To collect that information, I spent much time, money, and labor. I have, either in former or later years, examined these works, from their northeastern extremity, in New York, to the Tennessee Valley, inclusive, visiting in person, not every one, but certainly every one of any importance, from the foot of the Alleghanies to the Missouri. I have examined, for them, the banks of the Mississippi, from Memphis to Prairie du Chien. My remarks sometimes show that they were made at different times, which the reader will excuse, I hope, as it would cost me more labor to correct, than that labor would benefit him.

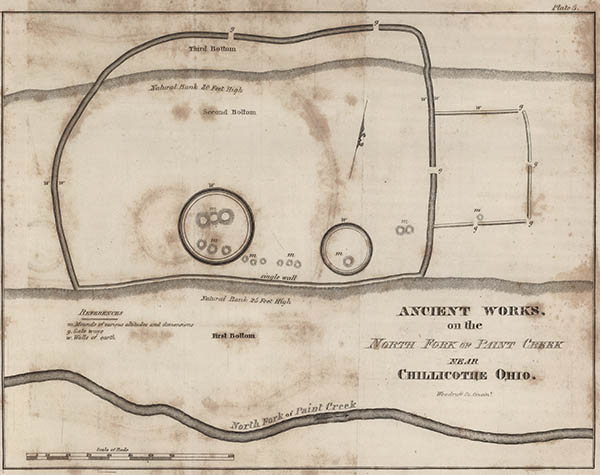

[pg 6] Perin Kent surveyed the Ancient Works on Main Paint creek; E. P. Kendrick, Esq. those on the North Fork of Pain creek; Joel Wright, Esq. county surveyor, those on the Little Miami; Roswell Mills, Esq. county surveyor, those in Perry county; B. P. Putnam, those at Marietta; Alexander Holmes, Esq. county surveyor, those near Newark; Guy W. Doan, Esq. and the Author, those at Circleville; Messrs. Abbot, Tracy, and Peebles, of Portsmouth, and William S. Murphy, Esq. of Chillicothe, assisted me in surveying and laying down those at Portsmouth. In addition to these names, I may add, that when the works were surveyed, it was done, almost always, in the presence, and with the aid of the most intelligent and respectable men in the several counties where the works are situated. And I was either present myself and assisted in the surveys, or carefully examined every thing described—sometimes before the survey, sometimes afterwards; but I always assured myself of the entire correctness of every thing stated as a fact. Indeed, I have recently—that is, within the year of 1833—been on the ground, and re-examined such works as yet remain in existence. I have also carefully read over my several descriptions of different articles, such as urns, beads, bracelets, the cloths found on our western mummies, idols, pipes, fish hooks and fish spears, &c. while each article lay before me, and in that way assured myself of the entire truth of my statements.

All the most important Ancient Works are either entirely or partly destroyed, and will soon be gone. No other accurate surveys were ever made of these works, but mine, and it is too late now for any to be made hereafter.

Every article mentioned in this portion of my volume as belonging to Mr. John D. Clifford, now belongs to Mr. Joseph Dorfeuille, of Cincinnati, and may be seen in his Western Museum. To him I am indebted, not only for opportunities of daily examining every article I have described, but for every book I have quoted in my work, and for the use, for several weeks, of his highly valuable library. [pg 7] It contains every work, of any note, relative to Mexico, the Pacific Islands, India, Java, and Egypt. For the use of this valuable collection, during several weeks in the year 1833, and for the kindness and hospitality of himself and interesting family, during that time, I feel truly grateful.

The remarks I have made on my Tour to Prairie du Chien and thence to Washington, have been greatly revised in this work; and it is quite possible, that in another edition I may still further revise that portion of my writings.

On a careful examination of the whole volume, I am satisfied that not one immoral idea is contained in it; and certainly I have endeavored to avoid every thing calculated to wound the feelings of any one. But my views are those prevalent in the West, honestly entertained by me; accompanied, I hope, by candor and liberality towards others differing with me in opinion.

I feel grateful for the extensive patronage this volume has received, and regret that about one hundred subscription papers are not returned to me, yet in the hands of agents, with a great many names on them. This is my reason for not publishing a list of my patrons' names, among whom would be seen the names of nearly every man of any distinction in the State. To all those gentlemen, and to the citizens of the State generally, I feel grateful for their kindness towards their friend,

CALEB ATWATER.

Columbus, December, 1833.

[pg 8]

CONTENTS

WESTERN ANTIQUITIES.

Antiquities of Indians of the present race, page 11. Antiquities belonging to people of European origin, 13. Antiquities of that ancient race of people who formerly inhabited the western parts of the United States, 18. In what part of the world similar antiquities are found, 19. Ancient Works near Newark, Ohio, 25. In Perry county, 30. At Marietta, 34. At Circleville, 45. On the Main Branch of Paint creek, 54. On the North Fork of Paint creek, 86. At Portsmouth, 56. On the Little Miami, 62. At Grave creek, below Wheeling, 92. Ancient Tumuli, 71. At Marietta, 75. At Circleville, 82. At Chillicothe, 85. Articles found in an ancient Mound in Cincinnati, 66. Articles discovered in an ancient Mound in Marietta, 79. Articles taken from ancient Mounds in and near Circleville, 82. Ancient Mounds of Stone, 90. Articles taken from an ancient Mound at Grave creek, 93. Ancient Mounds at St. Louis, and other places on the Mississippi, 94. Miscellaneous, remarks on the uses of the Mounds, 96. Places of Diversion, 99. Parallel Walls of Earth, 103. Conjectures respecting the Origin and History of the Authors of the Ancient Works in Ohio, &c., 105. Idol discovered near Nashville, 117. At what period did the Ancient Race of People arrive in Ohio? 120. How long did they reside here? 124. What was their number? 127. The state of the Arts among them, 128. Urns discovered at Chillicothe, 132. Dress of the Mummies, 134. Their Scientific Acquirements, 138. Religious Rites and Places of Worship, 140. What finally became of this People, 145. Description of the Teocalli of the Mexicans, from Humboldt, 153.

TOUR PRAIRIE DU CHIEN.

Maysville, Kentucky, 172. Cincinnati, 173. Louisville, 184. Scenery along the Ohio river, 194. Mouth of the Ohio, 196. Mississippi river and its tributaries, 199. Missouri river and its branches, 201. Future prospects of the people of the United States, 203. St. Louis, Missouri, 210. Expedition leaves St. Louis, 227. Keokuk village and Lower rapids, 229. Beautiful country below Rock island, 234. Galena, 238. Arrival at Prairie du Chien, 239. First Indian council, 241. Treaties made and mineral country ceded to the United States, 243. Origin of the North American Indians, 248. Indian form of government, 273. Manners and customs of the Indians, 278. Polygamy among the Indians, 285. Character and influence of Indian women, 289. Bucktail Bachelor, 293. Gambling among the Indians, 296. Indian eloquence, 298. Indian poetry, music and dancing, 303. Savage and civilized life compared, 315. Civilization of the Indians, 327. Wisconsin old maid and departure of the Indians, 333. Parting with the people of Prairie du Chien, 335. Wisconsin river, 337.

TOUR TO WASHINGTON CITY.

Sublime and impressive views along the Wisconsin, 340. Dodgeville, 344. Gratiot's Grove, 347. Mineral country and the Northwest, 348. Vincennes, 359. Miami country, 361. Scioto country, 363. Allegahny mountains, 365. Rocky mountains, 371. Washington city and the love of power, 376.

Franklinton and Columbus, 393.

Appendix, 398.

A

DESCRIPTION

OF THE

ANTIQUITIES

DISCOVERED

IN THE WESTERN COUNTRY;

ORIGINALLY COMMUNICATED

TO THE AMERICAN ANTIQUARIAN SOCIETY,

BY

CALEB ATWATER.

[pg 9]

DESCRIPTION OF ANTIQUITIES.

Our antiquities have been noticed by a great number of travelers, few of whom ever saw one of them, or, who riding at full speed, had neither the industry, the opportunity, nor the ability to investigate a subject so intricate. They have frequently given to the world such crude and indigested statements, after having visited a few ancient works, or heard the idle tales of persons incompetent to describe them, so that intelligent persons residing on the very spot, would never suspect what works were intended to be described!!It has somehow happened, that one traveler has seen an ancient work, which was once a place of amusement for those who erected it, and he concludes, that none but such were ever found in the whole country. Another in his journey sees a mound of earth, with a semicircular pavement on the east side of it; and at once he proclaims it to the world as his firm belief, that ALL our ancient works were places of devotion, dedicated to the worship of the sun. A succeeding tourist falls in with an ancient military fortress, and thence concludes that ALL our ancient works were raised for military purposes. One person finds something about these works of English origin, and, without hesitation, admits the supposition that they were erected by a colony of Welchmen. Others again, find articles in and near these ancient works, evidently belonging to the Indians, [pg 10] to people of European origin, and to that Scythian race of men who erected all our mounds of earth and stones. They find, too, articles scattered about and blended together, which belonged not only to different nations, but to different eras of time, remote from each other—they are lost in a labyrinth of doubt. Should the inhabitants of the Western States, together with every written memorial of their existence, be swept from the face of the earth, though the difficulties of future antiquaries, would be increased, yet they would be of the same KIND with those which now beset and overwhelm the superficial obverver.*

Our antiquities belong not only to different eras, in point of time, but to several nations; and those articles belonging to the same era and the same people, were intended by their authors to be applied to many different uses.

We shall divide these antiquities into three classes. 1. Those belonging to Indians of the present race.—2. To people of European origin;—and 3. Those of that people who raised our ancient forts and tumuli.

[pg 11] Permit me here to premise, that in order to arrive at a result which shall be, to a certain extent, satisfactory to the candid inquirer after truth, it is necessary, not only to examine with care, and describe with fidelity, those antiquities which are found in Ohio, but occasionally to cast a glance at those, found in other States, especially whenever they evidently, in common with ours, belong to the same people and the same era of time.

1. ANTIQUITIES OF INDIANS OF THE PRESENT RACE.

Those antiquities, which, in the strict sense of the term, belong to the North American Indians, are neither numerous nor very interesting. They consist of rude stone axes and knives, of pestles used in preparing maize for food, of arrowheads, and a few other articles so exactly similar to those found in all the Atlantic States, that a description of them is deemed quite useless. He who wishes to find traces of Indian settlements, either numerous, or worthy of his notice, must visit the shore of the Atlantic, or the banks of the larger rivers, emptying themselves into it, on the eastern side of the Alleghanies. The sea spreads out a continual feast before men in a savage state, little versed in the arts of civilized life, who look upon all pursuits as degrading to their dignity as men, except such as belong either to war or the chase. Having once found the ocean, there they fix their abode, and never leave it, until they are compelled to do so by a dense population, or the overwhelming force of a powerful and victorious foe. There they cast their lines, drag their nets, or rake up the shell fishes. Into the sea they drive the bounding roe with their dogs, and pursue him through the waves in their canoes. When they are compelled to leave the sea, they follow up the larger streams, where their finny prey abounds in every brook, and the deer, the bear, the elk, the moose, or the buffalo, feeds on every hill. Whatever the earth or water spontaneously produces, they take, and are satisfied. [pg 12] The ocean supplied them with never failing abundance; and the wild animals, feeding in immense numbers through the fine vales and over the fertile hills of New England, two centuries since, were, it is believed, more numerous than they ever were in Ohio. That species of beach which affords the nut on which, in autumn, winter and spring, the deer and several other kinds of animals feed, thrive and fatten, was once much more abundant there than it ever was in this State. Hence the wild animals were more numerous there than here; hence too the reason why the Indian population was more dense in the east than it was in the west. It is believed, that when America was first visited by Europeans, our prairies were too wet for the habitations of men. Besides if our Indians came from Asia by the way of Behring's Strait, they would naturally follow down the great chain of our northwestern lakes and their outlets, nearly or quite to the sea. This may be one reason why the Indian population, at the time when our ancestors first found them there, was more dense in the northern than in the southern, in the eastern than in the western parts, of the present United States. That it was so, our own history incontestably proves. Hence we deduce the reason, why the cemeteries of Indians are so large and numerous in the eastern, and so small and few in the western States. Hence the numerous other traces of Indian settlements, such as the immense piles of the shells of oysters, clams. &c., all along the sea shore, the great number of arrowheads and other articles belonging to them, in the eastern States, and their paucity here. There, we see the most indubitable evidences of the Indians having resided from very remote ages. Here, a few Indian cemeteries may be found, but they are never large, and when they are opened, ten chances to one but some article is discovered, which shows that the person had been buried since America was visited by people of European origin. An Indian's grave may frequently be known by the manner in which he was interred, which was generally in a sitting or an upright posture. [pg 13] Wherever we behold a number of holes in the earth, without any regard to regularity, of about a foot and a half or two feet in diameter, there by digging a few feet, we can generally find an Indian's remains. Such graves are most common along the southern shore of lake Erie, which was formerly inhabited by the Cat and Ottoway Indians. Such graves are quite common in and near the small ancient works in that part of this state. They generally interred with the deceased, something of which he had been fond in his life time; with the warrior, his battle axe; with the hunter, his bow and arrows, and that kind of wild game of which he had been the fondest, or the most successful in taking; hence the teeth of the otter are found in the grave of one, those of the bear or the beaver in another. One had been most successful in hunting the turkey, whilst another had most signalized himself by fishing. The skeleton of the turkey is found in the grave of the former; muscle shells or fishes' bones in the grave of the latter.

2. ANTIQUITIES BELONGING TO PEOPLE OF EUROPEAN ORIGIN.

Although this division of my subject may excite a smile, when it is recollected, that three centuries have not yet elapsed since this country has been visited by Europeans; yet, as articles derived from an intercourse, which has been kept up for more than one hundred and fifty years past, between the aborigines and several European nations, are sometimes found here; and as these articles, thus derived, are frequently blended with those really very ancient, I beg leave to retain this division of antiquities. The French were the first Europeans who traversed the territory included within the limits of the present State of Ohio. At exactly what time they first frequented these parts, and especially lake Erie, I have not been able to ascertain; but from authentic documents, published at Paris, in the seventeenth century, we do know that they had large establishments in the territory belonging to the [pg 14] Six Nations, as early at least as 1655.* "A quarto volume in Latin, written by Francis Creuxieus, a jesuit, was published at Paris, in 1664, and is entitled, 'Historiĉ Canadencis, seu Novĉ Franciĉ libri decem ad annum usque Christi MDCLVI.' It states that a French colony was established in the Onondaga territory about the year 1655, and it describes that highly interesting country: 'Ergo biduo post ingenti agmine deductus est ad locum gallorum sedi atque domicillio destinatum, leucas quatuor dissitum a pago, ubi primum pedum fixerat, bix quidquam a natura videre sit absolutius: ac si ans ut in Gallia, uteraque Europa, accederat, haud temere certaret cum Baiis. Pratum ingens cingit undique silva cĉdua ad ripam Lacus Gannanentĉ, quo Nationes quatuor, principes Iroquoiĉ, totius regionis tanquam ad centrum navigolis confluere perfacile queant, et unde vicissim facillimus aditus sit ad eorum singulas, per amnes lacusque circumfluentes. Ferinĉ copia certat cum copia piscium, atque ut ne desit quidquam, turtures eo indique sub veris initium convolant, tanto numero, ut reti capianter piscium quidem certe volant, ut piscatores esse feranter qui unius noctis spatium anguillas ad mille singuli, hamo capiant. Pratum intersecant fontes duo, centum prope passu salter ab altero dissiti: alterius aqua salsa salis optimi copium subministrat, alterius lympha dulcis ad potionem est; et quod mirere, uterque ex uno eademque colle scaturet.'

"It appears from Charlevoix's History of New France, that missionaries were sent to Onondaga in 1654; that they built a chapel and made a settlement; that a French colony was established there under the auspices of Le Sieur Depuys in 1656, and retired in 1658. When La Salle started from Canada and went down the Mississippi in 1679, he discovered a large plain between the lake of [pg 15] the Hurons and the Illinois, in which was a fine settlement belonging to the Jesuits."*

From this time forward the French are known to have traversed that part of this State which borders on lake Erie and the Ohio river, and the larger streams which are their tributaries. Under La Salle, father Hennepin and others, they were constantly traversing this territory in their journies to and from the valley of the Mississippi. Like other Europeans of that period, they took possession of the countries which they visited, in the name of their sovereign, and, not unfrequently, left some memorial of having done so, especially in the mouths of the large rivers and in the most remarkable ancient works. At many of the most remarkable places which they discovered, after singing "Te Deum," they affixed the arms of France to some tree, deposited a medal in some remarkable cave, tumulus, or ancient fort, or in the mouth of some large river.— Tonti, a Frenchman who accompanied La Salle in his first expedition from Canada to the Mississippi, informs us, in an account of this expedition, published at Paris in 1697, that at the mouth of the river last mentioned, the arms of France were fastened to a tree, "Te Deum" sung, formal possession of the country taken in the name of Louis XIV., and several huts built, surrounded by an entrenchment. Similar ceremonies were gone through at the mouth of the Illinois, the Wabash, and Ohio, as we learn from several French travelers of that day, who published their accounts at Paris in the seventeenth century. Is it strange, then, that we should find similar medals, &c. at the mouths of other rivers, such as the great and little Miami, the Scioto, and especially the Muskingum? That medals were deposited in many places in this country, father Hennepin, Touti, Joutel, and others, inform us: that similar medals been found at other places is also certain.

[pg 16] A medal was found several years since, in the mouth of the Muskingum river, by the late Hon. Jehiel Gregory. It was a thin, round plate of lead, several inches in diameter; on one side of which, I was informed by Judge Gregory, was the French name of the river in which it lay, "Petit-belle riviere," and on the other, "Louis XIV."

Near Portsmouth, a flourishing town at the mouth of the Scioto, a medal was found in alluvial earth, several years since, by a Mr. White, a number of feet below the surface, belonging, probably, to a recent era of time. This medal, I regret to state, is not in my possesion, but it has been described to me by Gen. Robert Lucas and the Hon. Ezra Osborn. It was masonic; the device on one side of it represented a human heart, with a sprig of cassia growing out of it; on the other side was a temple, with a cupola and spire, at the summit of which was a half moon, and there was a star in front of the temple. There were Roman letters on both sides of this medal, but what they were, Gen. Lucas and Judge Osborn have forgotten; they were probably abbreviations. That this medal had an European, and probably a French origin, there is little doubt, and belonged to a recent era of time.

In Trumbull county, several coins were found, not many years since, which, for a time, excited a considerable share of curiosity, until they were carefully examined by the present Governor of this state, who found that on one side of them was "George II." and on the other, "Caroline," and dated in the reign of that prince.

In Harrison county, I have been credibly informed, that several coins were found near an ancient work, evidently of European origin, belonging to a very recent era, compared with that of the ancient works where they reposed. These coins bore the name, and were dated in the reign of one of the English Charleses.

Near the mouth of Derby Creek, not far from Circleville, I have been credibly informed that a Spanish medal was found several years since, in a very good state of preservation, [pg 17] from which we learn that it was given by a Spanish Admiral to some person under the command of De Soto, who landed in Florida in 1538. There seems to me to be no great difficulty in accounting for such a medal being found here, near a water which runs into the Gulf of Mexico, even at such a distance from Florida, when it is recollected that a party of De Soto's men, an exploring company, which he sent out to reconnoiter the country, never returned to him nor were heard of afterwards. This medal might have been brought and lost where it was found, by the person to whom it was given, or by some Indian, who had rather have it in his own possession than in his captive's pocket.

Swords, gun barrels, knives, pickaxes, and implements of war, are often found along the banks of the Ohio, which had been left there by the French, when they had forts at Pittsburgh, Ligonier, St. Vincents, &c.

The traces of a furnace of fifty kettles, said to exist in Kentucky, a few miles in a southeastern direction from Portsmouth, appear to me to belong to the same era, and owe their origin to the same people.

Several Roman coins, said to have been found in a cave near Nashville, in Tennessee, bearing date not many centuries after the Christian era, have excited some interest among antiquaries. They were either discovered where the finder had purposely lost them, or, what is more probable, had been left there by some European since this country was traversed by the French.

That a Frenchman should be in possession of a few Roman coins, and that he should deposit them in some remarkable cave which he chanced to visit in his travels, is not surprising. That some persons have purposely lost coins, medals, &c. &c. in caves which they knew were about to be explored; or deposited them in tumuli, which they knew were about to be opened, is a well known fact, which has occurred at several place this western country.

In one word, I will venture to assert, that there never has been found a medal, coin, or monument, in all North [pg 18] America, which had on it one or more letters, belonging to any alphabet, now or ever in use among men of any age or country, that did not belong to Europeans or their descendants, and had been brought or made here since the discovery of America by Christopher Columbus.

3. ANTIQUITIES OF THE PEOPLE WHO FORMERLY INHABITED THE WESTERN PARTS OF THE UNITED STATES.

It is time to consider the third, last, and most highly interesting class of antiquities, which comprehends those belonging to that people who erected our ancient forts and tumuli; those military works, whose walls and ditches cost so much labor in their structure; those numerous and sometimes lofty mounds, which owe their origin to a people far more civilized than our Indians, but far less so than Europeans. These works are interesting, on many accounts, to the antiquarian, the philosopher, and the divine, especially when we consider the immense extent of country which they cover; the great labor which they cost their authors; the acquaintance with the useful arts, which that people had, when compared with our present race of Indians; the grandeur of many of the works themselves; the total absence of all historical records, or even traditionary accounts respecting them; the great interest which the learned have taken in them; the contradictory and erroneous accounts which have generally been given of them: to which we may add, the destruction of them which is going on in almost every place wherethey are found in this whole country, have jointly contributed to induce me to bestow no inconsiderable share of attention to this class of antiquities. They were once forts, cemeteries, temples, altars, camps, towns, villages, race grounds, and other places of amusement, habitations of chieftains, videttes, watch towers, monuments, &c. These ancient works, especially the mounds, both of earth and stone, are found in every quarter of the habitable globe.

IN WHAT PARTS OF THE WORLD ANCIENT WORKS OF THIS KIND ARE FOUND.

These ancient works, so much talked about, and so little understood, are spread over an immense extent of country, in Europe and the northern parts of Asia. They may be traced from Wales to Scotland on the island of Britain;— they are found in Ireland, in Normandy, in France, in Sweden, and quite across the Russian empire, our continent. In Africa we see pyramids, which derive their origin from the same source. In Judea, and throughout all Palestine, works similar to ours exist. In Tartary they abound in all the steppes. I know not whether Lewis and Clarke saw any of these works on the Columbia river; but they did not traverse that country by land, and had of course but little opportunity to discover them, if there.— But on this side of the Rocky mountains they did see them frequently; and I have little doubt of their existing all the way, from the spot where, we are informed, the ark of Noah rested, to our northwestern lakes, down them and their outlets, as far as the Black river country, on the southern shore of lake Ontario, in New-York.

On the south side of Ontario, one not far from Black river, is the farthest in a northeastern direction, on this continent. One on the Chenango river, at Oxford, is the farthest south, on the eastern side of the Alleghanies.— These works are small, very ancient, and appear to mark the utmost extent of the settlement of the people who erected them, in that direction. Coming from Asia, finding our great lakes, and following them down thus far; were they driven back by the ancestors of our Indians? and, were the small forts above alluded to, built in order to [pg 20] protect them from the aborigines who had before that time settled along the Atlantic coast? In traveling towards lake Erie, in a western direction from the works above mentioned, a few small works are occasionally found, especially in Genesee county; but they are few and small, until we arrive at the mouth of Cataraugus creek, a water of lake Erie, in Cataraugus county, in the State of New-York, where Governor Clinton, in his "Memoir, &c." says a line of forts commences, extending south upwards of fifty miles, and not more than four or five miles apart. There is said to be another line of them parallel to these, which generally contain a few acres of ground only, whose walls are only a few feet in height. For an able account of the antiquities in the western parts of New-York, we must again refer to Governor Clinton's Memoir, not wishing to repeat what he has so well said.

If the works already alluded to, are real forts, they must have been built by a people few in number, and quite rude in the arts of life. Traveling towards the southwest, these works are frequently seen, but like those already mentioned, they are comparatively small, until we arrive on the Licking, near Newark, where are some of the most extensive and intricate, as well as interesting, of any in this State, perhaps in the world. Leaving these, still proceeding in a southwestern direction, we find some very extensive ones at Circleville. At Chillicothe there were some, but the destroying hand of man has despoiled them of their contents, and entirely removed them. On Paint creek are some far exceeding all others in some respects, where, probably was once an ancient city of great extent. At the mouth of the Scioto, are some very extensive ones, as well as at the mouth of the Muskingum. In fine, these works are thickly scattered over the vast plain from the southern shore of lake Erie, to the Mexican Gulf, increasing in number, size and grandeur as we proceed towards the south. They may be traced around the Gulf, across the province of Texas into New-Mexico, and all the way into [pg 21] South America. They abound most in the vicinity of good streams, and are never, or rarely found, except in a fertile soil. They are not found in the prairies of Ohio, and rarely in the barrens, and they are small, and situated on the edge of them, and on dry ground. From the Black river country in New-York, to this State, I need say no more concerning them; but at Salem, in Ashtabula county, there is one on a hill, which merits a few words, though it is a small one compared with others farther south. The work at Salem, is on a hill near Coneaught river, if my information be correct, and is about three miles from lake Erie. It is round, having two parallel circular walls, and a ditch between them. Through these walls, leading into the inclosure, are a gateway and a road, exactly like a modern turnpike, descending down the hill to the stream by such a gradual slope, that a team with a wagon might easily either ascend or descend it, and there is no other place by which these works could be approached, without considerable difficulty. Within the bounds of this ancient enclosure, the trees which grew there were such as denote the richest soil in this country, while those growing on the outside of these ruins, were such as denote the poorest.

On the surface of the earth, within this circular work, and immediately below it, pebbles rounded, and having their angles worn off in water, such as are now seen on the present shore of the lake, are found; but they are represented as bearing visible marks of having been burned in a hot fire. Bits of earthen ware, of a coarse kind, and of a rude structure, without any glazing, are found here on the surface, and a few inches below it. This ware is represented to me as having been manufactured of sand stone and clay. My informant says, within this work are sometimes found skeletons of a people of small stature; which, if true, sufficiently identifies it to have belonged to that race of men who erected our tumuli. The vegetable mould covering the surface within the works, is at least ten inches in depth. In these same works have been found articles, [pg 22] evidently belonging to Indians, of their own manufacture, as well as others, which they had derived from their intercourse with Europeans and their descendants. I mention the fact here, thus particularly, in order to save the repetition of it, in describing nearly every work of this kind, especially along the shore of lake Erie, and the banks of the larger rivers. This circumstance I wish the reader to keep in mind. Indian antiquities are always either on, or a very small distance below, the surface, unless buried in some grave; whilst articles, evidently belonging to that people who raised our mounds, are frequently found many feet below the surface, especially in river bottoms.

Still proceeding in a southwestern direction, there are, at different places, several small ancient works, scattered over the country, some in regular forms, and others appear to have been thrown up to suit the ground where they are situated; but their walls are only a few feet in height, encompassing, generally, but a few acres, with ditches of no great depth, evidently showing the population to have been inconsiderable.

I have been informed, that in the north part of Medina county, Ohio, there are some works, near one of which, a piece of marble, well polished, was lately found. It might have been a composition of clay and sulphate of lime or plaster of Paris, such as I have often seen in and about ancient works along the Ohio river. A common observer would mistake the one for the other, which I am disposed to believe was the case here.

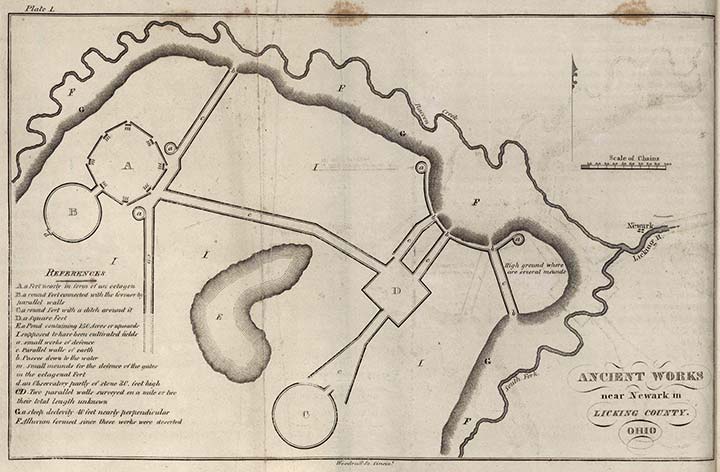

ANCIENT WORKS NEAR NEWARK, OHIO.

Proceeding still to the southward, the ancient works become more and more numerous, and more intricate, and of greater size; denoting the increase of their authors, in number, strength, and a better acquaintance with the art of constructing them. At length we reach the interesting ones on two branches of the Licking, near Newark, in Licking county, Ohio, which, on many accounts, are quite as remarkable as any others in North America, or, perhaps in any part of the world.

By referring to the scale on which they are projected, it will be seen that these works are of great extent.

A, is a fort containing about forty acres within its walls, which are, generally, I should judge, about ten feet high. Leading into this fort, are eight openings or gateways, about fifteen feet in width; in front of which, is a small mound of earth, in height and thickness resembling the outer wall. (See m, m, m, m, m, m, m.) These small mounds are about four feet longer than the gateway is in width; otherwise they look as if the wall had been moved into the fort eight or ten feet. These small mounds of earth were probably intended for the defence of the gates, opposite to which they are situated. The walls of this work, consisting of earth, are taken from the surface so carefully and uniformly, that it cannot now be discovered from what spot. They are as nearly perpendicular as the earth could be made to lie.

B, is a round fort, containing twenty-two acres, connected with A, by two parallel walls of earth of about the same height, &c. as those of A. At d, is an OBSERVATORY, built [pg 26] partly of earth and partly of stone. It commanded a full view of a considerable part, if not all the plain, on which these ancient works stand; and would do so now, were the thick growth of ancient forest trees, which clothe this tract, cleared away. Under this observatory, was a passage, from appearances, and a secret one probably, to the water course which once run near this spot, but has since moved farther off.

C, is a circular fort, containing about twenty-six acres, having a wall around it, which was thrown out of a deep ditch on the inner side of the wall. This wall is now from twenty-five to thirty feet in height; and when I saw this work, the ditch was half filled with water, especially on the side towards E. There are parallel walls of earth, c, c, c, c, c, c, generally five or six rods apart, and four or five feet in height. Their extent may be measured by the reader, by referring to the scale annexed to the plates.

D, is a square fort, containing twenty acres, whose walls are similar to those of A.

E, is a pond, covering from one hundred and fifty to two hundred acres; which was a few years since entirely dry, so that a crop of Indian corn was raised where the water is now ten feet in depth, and appears still to be rising. This pond sometimes reaches to the very walls of C, and to the parallel walls towards its northern end.

F, F, F, F, is the interval, or alluvion, made by the Raccoon and south fork of Licking river, since they washed the foot of the hill at G, G, G. When these works were occupied, we have reason to believe that these streams washed the foot of this hill, and as one proof of it, passages down to the water have been made of easy ascent and descent, at b, b, b, b.

G, G, G, an ancient bank of the creeks, which have worn their channels considerably deeper than they were when they washed the foot of this hill. These works stand on a large plain, which is elevated forty or fifty feet above [pg 27] the interval F, F, F, and is almost perfectly flat, and as rich a piece of land as can be found in any country. The reader will see the passes, where the authors of these works entered into their fields at I, I, I, I, I, and which were probably cultivated. The watch towers, a, a, a, a, were placed at the ends of parallel walls, or ground as elevated as could be found on this extended plain. They were surrounded by circular walls, now only four or five feet in height. It is easy to see the utility of these works, placed at the several points where they stand.

C, D, two parallel walls, leading probably to other works, but not having been traced more than a mile or two, are not laid down even as far is they were surveyed.

The high ground, near Newark, appears to have been the place, and the only one which I saw, where the ancient occupants of these works buried their dead, and even these tumuli appeared to me to be small. Unless others are found in the vicinity, I should conclude, that the original owners, though very numerous, did not reside here during any greath length of time. I should not be surprised if the parallel walls C, D, are found to extend from one work of defence to another, for the space of thirty miles, all the way across to the Hockhocking, at some point a few miles north of Lancaster. Such walls having been discovered at different places, probably belonging to these works, for ten or twelve miles at least, leads me to suspect that the works on Licking were erected by people who were connected with those who lived on the Hockhocking river, and that their road between the two settlements was between these parallel walls.

If I might be allowed to conjecture the use to which these works were originally put, I should say, that the larger works were really military ones of defense; that their authors lived within the walls; that the parallel walls were intended for the double purposes of protecting persons in times of danger, from being assaulted while passing from one work to another, and they might also serve as fences, [pg 28] with a very few gates, to fence in and inclose their fields, at I, I, I, I, as the plate will show.

The hearths, burnt charcoal, cinders, wood, ashes, &c. which were uniformly found in all similar places, that are now cultivated, have not been discovered here; this plain being probably an uncultivated forest. I found here, several arrowheads, such as evidently belonged to the people who raised other similar works.

The care which is every where visible about these ruins, to protect every part from a foe without; the high plain on which they are situated, which is generally forty feet above the country around it; the pains taken to get at the water, as well as to protect those who wished to obtain it; the fertile soil, which appears to me to have been cultivated, are circumstances not to be overlooked; they speak volumes in favour of the sagacity of their authors.

A few miles below Newark, on the south side of the Licking, are some of the most extraordinary holes, dug in the earth, for number and depth, of any within my knowledge, which belonged to the people we are treating of. In popular language, they are called "wells," but were not dug for the purpose of procuring water, either fresh or salt.

There are at least a thousand of these "wells;" many of them are now more than twenty feet in depth. A great deal of curiosity has been excited, as to the objects sought for, by the people who dug these holes. One gentleman nearly ruined himself, by digging in and about these works, in quest of the precious metals; but he found nothing very precious. I have been at the pains to obtain specimens of all the minerals, in and near these wells. They have not all of them been put to proper tests; but I can say, that rock crystals, some of them very beautiful, and horn stone, suitable for arrow and spear heads, and a little lead, sulpher, and iron, was all that I could ascertain correctly to belong to the specimens it my possession. Rock crystals, and stone arrow and spear heads, were in great repute among them, if we are to judge from the numbers of them [pg 29] found in such of the mounds as were common cemeteries. To a rude people, nothing would stand a better chance of being esteemed, as an ornament, than such articles.

On the whole, I am of the opinion, that these holes were dug for the purpose of procuring the articles above named; and that it is highly probable a vast population, once here, procured these, in their estimation, highly ornamental and useful articles. And it is possible that they might have procured some lead here, though by no means probable, because we no where find any lead which ever belonged to them, and it will not very soon, like iron, become an oxyde, by rusting.

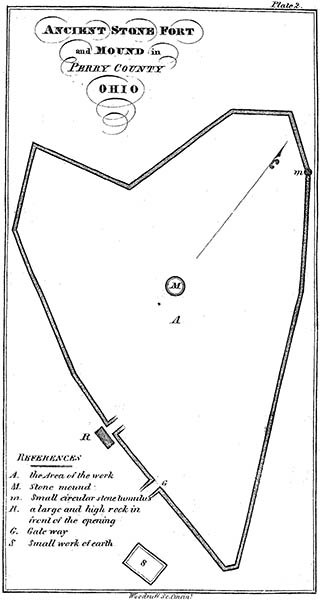

ANCIENT WORKS IN PERRY COUNTY, OHIO.

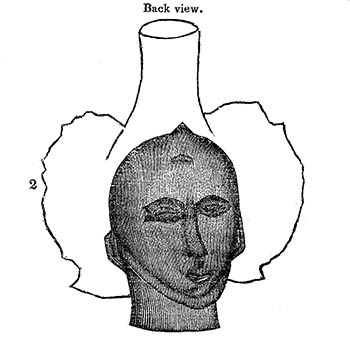

Southwardly from the great works on the Licking, four or five miles in a northwestern direction from Somerset, the seat of justice for Perry county, and on section twenty-one, township seven, range sixteen, is an ancient work of stone. [See the plate.]

A, is the area of this work. M, a stone mound near the center of it. This stone mound is circular, and in form of a sugar loaf, from twelve to fifteen feet in height. There is a smaller circular stone tumulus at m, standing in the wall, which encloses the work, and constituting a part of it.

R, is a large and high rock, lying in front of an opening in the outer wall. This opening is a passage between two large rocks, which lie in the wall, of from seven to ten feet in width. These rocks, on the outside, present a perpendicular front of ten feet in altitude, but after extending fifty yards into the enclosure, they enter the earth and disappear. There is a gateway at G, much as is represented in the plate.

S, is a small work, whose area is half an acre; the walls are of earth, and of a few feet only in height. This large stone work contains within its walls forty acres and upwards. The walls, as they are called in popular language, consist of rude fragments of rocks, without any marks of any iron tool upon them. These stones lie in the utmost disorder, and if laid up in a regular wall, would make one seven feet or seven feet six inches in height, and from four to six feet in thickness. I do not believe this ever to have been a military work, either of defense or offense; but if a military work, it must have been a temporary camp. From the circumstance of this work's containing two stone tumuli, [pg 33] such as were used in ancient times, as altars and as monuments, for the purpose of perpetuating the memory of some great era, or important event in the history of those who raised them, I should rather suspect this to have been a sacred enclosure, or "high place," which was resorted to on some great anniversary. It is on high ground, and destitute of water, and of course, could not have been a place of habitation for any length of time. It might have been the place where some solemn feast was annually held, by the tribe by which it was formed. The place has become a forest, and the soil is too poor to have ever been cultivated by a people who invariably chose to dwell on a fertile spot. These monuments of ancient manners, how simple, and yet how sublime! Their authors were rude, and unacquainted with the use of letters, yet they raised monuments calculated almost for endless duration, and speaking a language as expressive as the most studied inscriptions of later times upon brass and marble. These monuments, their stated anniversaries and traditionary accounts, were their means of perpetuating the recollection of important transactions. Their authors are gone; their monuments remain: But the events which they were intended to keep in the memory, are lost in oblivion.

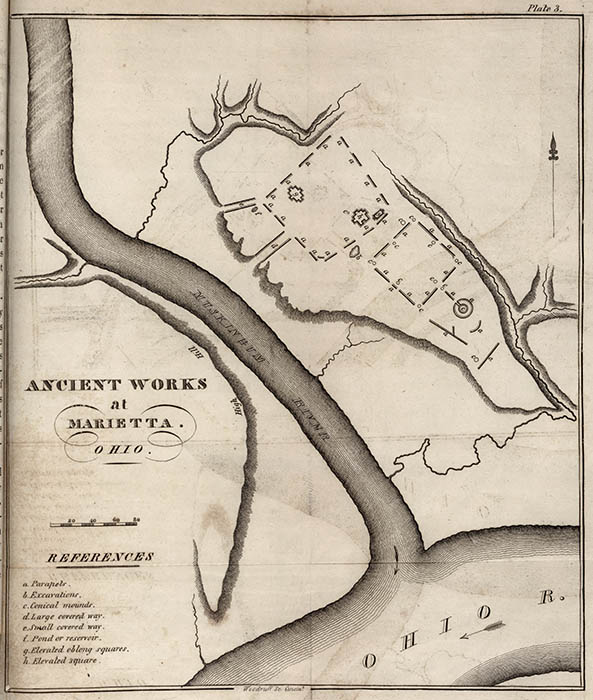

ANCIENT WORKS AT MARIETTA, OHIO.

Having already described several ancient works, either on or near the waters of the Muskingum, I shall trace them down that river. But there are none of any considerable note, except those on the Licking, which falls into that stream at Zanesville, until we arrive at some situated near its banks in Morgan county, which, however, have not been surveyed. These are mounds of earth and stones, and their description is reserved until we arrive at that part of this memoir, which will be devoted to a consideration of that class of antiquities.

Proceeding down the Muskingum to its mouth, at Marietta, are some of the most extraordinary ancient works any where to be found. They have been often examined, and as often very well described; yet as some additional facts have come to my knowledge, and as other works in many parts of the western country are similar to them; and as comparisons ought to be instituted between works evidently of the same class, I have ventured to collect together a mass of facts concerning them, derived from several intelligent persons, who have published their statements, as well as some from others who have obligingly laid before me additional information.

Manassah Cutler, LL. D., many years since, published an accurate account of these works. Next followed "The Journal of a Tour" into this country, by Thaddeus M. Harris, D. D., in which may be found much useful information concerning them, accompanied by a diagram sketch of them, very accurately drawn from actual survey, by Gen. Rufus Putnam, of Marietta. I have carefully compared these well written accounts with those which I have [pg 37] received from Dr. S.P. Hildreth, of Marietta, Gen. Edward W. Tupper, of Gallipolis, and several other gentlemen residing on the Ohio. From these highly respectable sources, I have drawn my information. These works have been more fortunate than many others of this kind in North America: no despoiling hand has been laid upon them; and no blundering, hasty traveler has, to my knowledge, pretended to describe them. The mound which was used as a cemetery is entire, standing in the burying ground of the present town. Cutler, Putnam, and Harris, are intelligent men.

It will be seen that I have quoted largely from Drs. Cutler and Harris; not, however, without first ascertaining that their accounts were perfectly correct, as to all the facts which they have stated.

* "The situation of these works is on an elevated plain above the present bank of the Muskingum, on the cast side, and about half a mile from its junction with the Ohio. They consist of walls and mounds of earth, in direct lines, and in square and circular forms.

"The largest square fort, by some called the town, contains forty acres, encompassed by a wall of earth, from six to ten feet high, and from twenty-five to thirty-six in breadth at the base. On each side are three openings, at equal distances, resembling twelve gateways. The entrances at the middle, are the largest, particularly on the side next to the Muskingum. From this outlet is a covert way, formed of two parallel walls of earth, two hundred and thirty-one feet distant from each other, measuring from center to center. The walls at the most elevated part, on the inside, are twenty-one feet in height, and forty-two in breath at the base, but on the outside average only five feet in height. This forms a passage of about three hundred and sixty feet in length, leading by a gradual descent to the low grounds, where, at the time [pg 38] of its construction, it probably reached the river. Its walls commence at sixty feet from the ramparts of the fort, and increase in elevation as the way descends towards the river; and the bottom is crowned in the center, in the manner of a well founded turnpike road.

"Within the walls of the fort, at the northwest corner, is an oblong elevated square, one hundred and eighty-eight feet long, one hundred and thirty-two broad, and nine feet high; level on the summit, and nearly perpendicular at the sides. At the center of each of the sides, the earth is projected, forming gradual ascents to the top, equally regular, and about six feet in width. Near the south wall is another elevated square, one hundred and fifty feet by one hundred and twenty, and eight feet high, similar to the other, excepting that instead of an ascent to go up on the side next the wall, there is a hollow way ten feet wide, leading twenty feet towards the center, and then rising with a gradual slope to the top. At the southeast corner, is a third elevated square, one hundred and eight, by fifty-four feet, with ascents at the ends, but not so high nor perfect as the two others. A little to the southwest of the center of the fort is a circular mound, about thirty feet in diameter and five feet high, near which are four small excavations at equal distances, and opposite each other. At the southwest corner of the fort is a semicircular parapet, crowned with a mound, which guards the opening in the wall. Towards the southeast is a smaller fort, containing twenty acres, with a gateway in the center of each side and at each corner. These gateways are defended by circular mounds.

"On the outside of the smaller fort is a mound, in form of a sugar loaf, of a magnitude and height which strike the beholder with astonishment. Its base is a regular circle, one hundred and fifteen feet in diameter; its perpendicular altitude is thirty feet. It is surrounded by a ditch four feet deep and fifteen feet wide, and defended by a parapet [pg 39] four feet high, through which is a gateway towards the fort, twenty feet in width. There are other walls, mounds, and excavations, less conspicuous and entire, which will be best understood by referring to the annexed drawings."

Some additional particulars respecting these works, are contained in the following extracts from a letter, written by Dr. S. P. Hildreth, of Marietta, to the author, dated the 8th of June, 1819.

"Mr. Harris, in his 'Tour,' has given a tolerably good account of the present appearance of the works, as to height, shape and form. (I must refer you to this work.) The principal excavation, or well, is as much as sixty feet in diameter, at the surface; and when the settlement was first made, it was at least twenty feet deep. It is at present twelve or fourteen feet; but has been filled up a great deal from the washing of the sides by frequent rains. It was originally of the kind formed in the most early days, when the water was brought up by hand in pitchers, or other vessels, by steps formed in the sides of the well.

"The pond, or reservoir, near the northwest corner of the large fort, was about twenty-five feet in diameter, and the sides raised above the level of the adjoining surface by an embankment of earth three or four feet high. This was nearly full of water at the first settlement of the town, and remained so until the last winter, at all seasons of the year. When the ground was cleared near the well, a great many logs that laid nigh, were rolled into it, to save the trouble of piling and burning them. These, with the annual deposit of leaves, &c., for ages, had filled the well nearly full; but still the water rose to the surface, and had the appearance of a stagnant pool. In early times, poles and rails have been pushed down into the water, and deposit of rotten vegetables, to the depth of thirty feet. Last winter the person who owns the well, undertook to drain it, by cutting a ditch from the well into the small "covert way;" and he has dug to the depth of about twelve feet, and let the [pg 40] water off to that distance. He finds the sides of the reservoir not perpendicular, but projecting gradually towards the center of the well, in the form of an inverted cone. The bottom and sides, so far as he has examined, are lined with a stratum of very fine, ash colored clay, about eight or ten inches thick; below which, is the common soil of the place, and above it, this vast body of decayed vegetation. The proprietor calculates to take from it several hundred loads of excellent manure, and to continue to work at it, until he has satisfied his curiosity, as to the depth and contents of the well. If it was actually a well, it probably contains many curious articles, which belonged to the ancient inhabitants.

"On the outside of the parapet, near the oblong square, I picked up a considerable number of fragments of ancient potters' ware. This ware is ornamented with lines, some of them quite curious and ingenious, on the outside. It is composed of clay and fine gravel, and has a partial glazing on the inside. It seems to have been burnt, and capable of holding liquids. The fragments, on breaking them, look quite black, with brilliant particles, appearing as you bold them to the light. The ware which I have seen, found near the rivers, is composed of shells and clay, and not near so hard as this found on the plain. It is a little curious, that of twenty or thirty pieces which I picked up, nearly all of them were found on the outside of the parapet, as if they had been thrown over the wall purposely. This is, in my mind, strong presumptive evidence, that the parapet was crowned with a palisade. The chance of finding them on the inside of the parapet, was equally good, as the earth had been recently ploughed, and planted with corn. Several pieces of copper have been found in and near to the ancient works, at various times. One piece, from the description I had of it, was in the form of a cup with low sides, the bottom very thick and strong. The small mounds in this neighborhood have been but slightly, if at all examined.

[pg 41] "The avenues, or places of ascent on the sides of the elevated squares, are ten feet wide, instead of six, as stated by Mr. Harris. His description, as to height and dimensions, are otherwise correct.

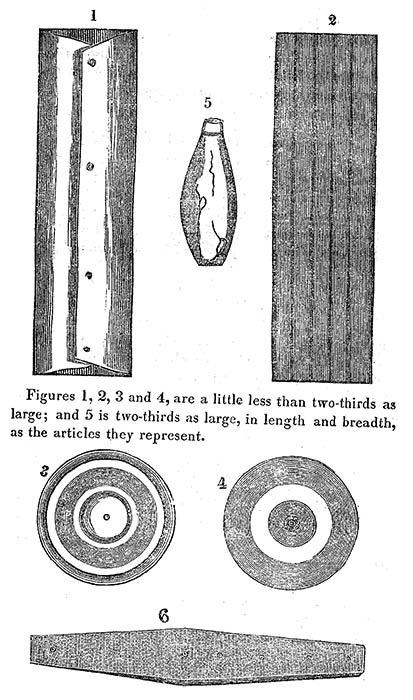

"There was lately found at Waterford, not far from the bank of the Muskingum, a magazine of spear and arrow heads, sufficient to fill a peck measure. They lay in one body, occupying a space of about eight inches in width and eighteen in length, and at one end about a foot from the surface of the earth, and eighteen inches at the other; as though they had been buried in a box, and one end had sunk deeper in the earth than the other. They were found by Mr. B. Dana, of Waterford, as he was digging the earth to remove a large pear tree. The spot was formerly covered by a house in the early settlement of the place. They appear never to have been used, and are of various lengths, from six to two inches; they have no shanks, but are in the shape of a triangle, with two long sides, thus, ![]() "

"

It is worthy of remark, that the walls and mounds were not thrown up from ditches, but raised by bringing the earth from a distance, or taking it up uniformly from the plain; resembling, in that respect, most of the ancient works at Licking, already described. It has excited some surprise that the tools have not been discovered here, with which these works were constructed. Those who have examined these ruins, seem not to have been aware, that with shovels made of wood, earth enough to have constructed these works might have been taken from the surface, with as much ease, almost, as if they were made of iron. This will not be as well understood on the east as the west side of the Alleghanies; but those who are acquainted with the great depth and looseness of our vegetable mould, which lies on the surface of the earth, and of course, the ease with which it may be raised by wooden tools, will cease to be astonished at what would be an immense labor in what geologists call "primitive" countries. Besides, had the people who raised these works, been in possession of, and [pg 42] used ever so many tools, manufactured from iron, by lying either on or under the earth, during all that long period which has intervened between their authors and us, they would have long since oxydized by "rusting," and left but faint traces of their existence behind them.

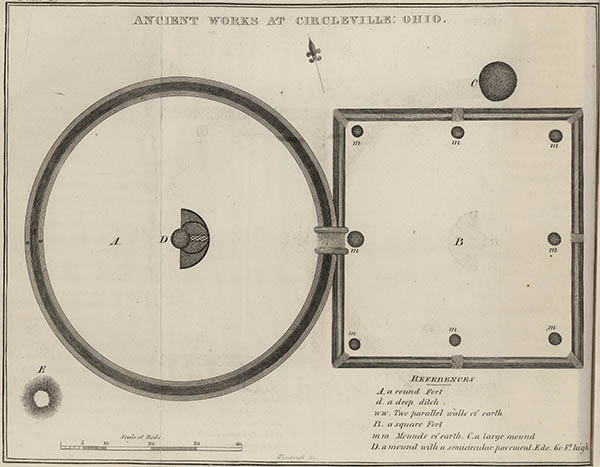

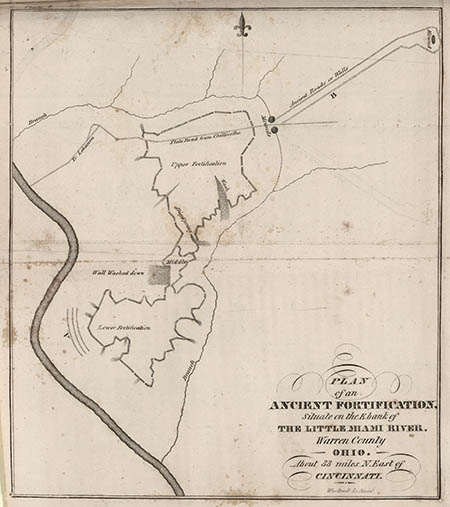

ANCIENT WORKS AT CIRCLEVILLE, OHIO.

Having noticed the principal works of this kind on the waters of the Muskingum, we shall next consider those which might have once been military works, on the waters of the Scioto.

From near Lower Sandusky, I am not informed of any worthy of notice, that is, "FORTS," until we arrive at Circleville, twenty-six miles south of Columbus.

These are situated not far from the junction of Hargus's creek with the latter river, which is on the east side of the river, and south side of the creek. By referring to the plate, the reader will be better enabled to understand the description which follows.

There are two forts, one being an exact circle, the other an exact square. The former is surrounded by two walls, with a deep ditch between them. The latter is encompassed by one wall, without any ditch. The former was sixty-nine rods in diameter, measuring from outside to outside of the circular outer wall; the latter is exactly fifty-five rods square, measuring the same way. The walls of the circular fort were at least twenty feet in height, measuring from the bottom of the ditch, before the town of Circleville was built. The inner wall was of clay taken up probably in the northern part of the fort, where was a low place, and is still considerably lower than any other part of the work. The outside wall was taken from the ditch which is between these walls, and is alluvial, consisting of pebbles worn smooth in water, and sand, to a very considerable depth, more than fifty feet at least. The outside of the walls is about five or six feet in height now; on the inside, the ditch is, at present, generally not more than fifteen feet. [pg 46] They are disappearing before us daily, and will soon be gone. The walls of the square fort, are, at this time, where left standing, about ten feet in height. There were eight gateways, or openings, leading into the square fort, and only one into the circular fort. Before each of these openings was a mound of earth, perhaps four feet high, forty feet perhaps in diameter at the base, and twenty or upwards at the summit. These mounds, for two rods or more, are exactly in front of the gateways, and were intended for the defense of these openings.

As this work was a perfect square, so the gateways and their watch-towers were equidistant from each other.— These mounds were in a perfectly straight line, and exactly parallel with the wall. Those small mounds were at m, m, m, m, m, m, m. The black line at d, represents the ditch, and w, w, represent the two circular walls.

D, shows the seite of a once very remarkable ancient mound of earth, with a semicircular pavement on its eastern side, nearly fronting, as the plate represents, the only gateway leading into this fort. This mound is entirely removed; but the outline of the semicircular pavement, may still be seen in many places, notwithstanding the dilapidations of time, and those occasioned by the hand of man. This mound, the pavement, the walk from the east to its elevated summit, the contents of the mound, &c., will be described under the head of mounds.

The earth in these walls was as nearly perpendicular as it could be made to lie. This fort had originally but one gateway leading into it on its eastern side, and that was defended by a mound of earth, several feet in height, at m, i. Near the center of this work was a mound, with a semicircular pavement on its eastern side, some of the remains of which may still be seen by an intelligent observer. The mound at m, i, has been entirely removed, so as to make the street level, from where it once stood.

[pg 47] B, is a square fort adjoining the circular one, as represented by the plate, the area of which has been stated already. The wall which surrounds this work, is generally, now, about ten feet in height, where it has not been manufactured into brick. There are seven gateways leading into this fort, besides the one that communicates with the square fortification; that is, one at each angle, and another in the wall, just half way between the angular ones. Before each of these gateways was a mound of earth of four or five feet in height, intended for the defense of these openings.

The extreme care of the authors of these works to protect and defend every part of the circle, is no where visible about this square fort. The former is defended by two high walls; the latter, by one. The former has a deep ditch encircling it; this has none. The former could be entered at one place only; this, at eight, and those about twenty feet broad. The present town of Circleville covers all the round, and the western half, of the square fort. These fortifications, where the town stands, will entirely disappear in a few years; and I have used the only means within my power, to perpetuate their memory, by the annexed drawing and this brief description.

Where the wall of the square fort has been manufactured into brick, the workmen found some ashes, calcined stones, sticks, and a little vegetable mould; all of which must have been taken up from the surface of the surrounding plain. As the square fort is a perfect square, so the gateways or openings are at equal distances from each other, and on a right line parallel with the wall. The walls of this work vary a few degrees from north and south, east and west; but not more than the needle varies, and not a few surveyors have, from this circumstance, been impressed with the belief, that the authors of these works were acquainted with astronomy. What surprised me, on measuring these forts, was the exact manner in which they had laid down [pg 48] their circle and square; so that after every effort, by the most careful survey, to detect some error in their measurement, we found that it was impossible, and that the measurement was much more correct, than it would have been in all probability, had the present inhabitants undertaken to construct such a work. Let those consider this circumstance, Who affect to believe these antiquities were raised by the ancestors of the present race of Indians. Having learned something of astronomy, what nation, living as our indians do, in the open air, with the heavenly bodies in full view, could have forgotten such knowledge?

Some hasty travelers, who have spent an hour or two here, have concluded that the "forts" at Circleville were not raised for military, but for religious purposes, because there were two extraordinary tumuli here. A gentleman in one of our Atlantic cities, who has never crossed the Alleghanies has written to me, that he is fully convinced that they were raised for religious purposes. Men thus situated, and with no correct means of judging, will hardly be convinced by any thing I can say. Nor do I address myself to them, directly or indirectly; for it has long been my maxim, that it is worse than vain to spend one's time in endeavoring to reason men out of opinions for which they never had any reasons.

The round fort was picketed in, if we are to judge from the appearance of the ground on and about the walls. Half way up the outside of the inner wall, is a place distinctly to be seen, where a row of pickets once stood, and where it was placed when this work of defense was originally erected. Finally, this work, about its wall and ditch, eight years since, presented as much of a defensive aspect as forts which were occupied in our wars with the French, in 1755, such as Oswego, Fort Stanwix, and others. These works have been examined by the first military men now living in the United States, and they have uniformly declared their opinion to be, that they were military works of defense.

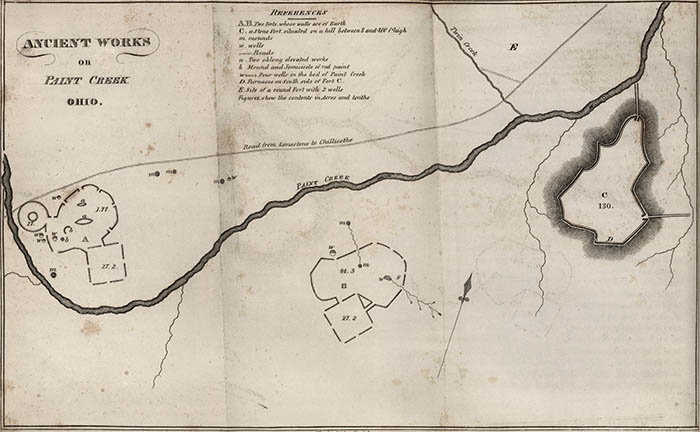

ANCIENT WORKS ON THE MAIN BRANCH OF PAINT CREEK, OHIO.

The nearest of these are situated about eleven, and the farthest fifteen miles, westwardly, from the town of Chillicothe. The plate will assist us in describing them; to which we refer. Their contents, in acres and tenths, are set down on the plate. These works were very carefully surveyed by Mr. Perrin Kent, and the drawing was made by George Wolfley, Esq., of Circleville.

We shall begin with work B, situated on the farms of Capt. George Yocan and Mr. John Harness. The gateways, it will be seen, are numerous, and are from eight to twenty feet wide. The walls are generally about ten feet high at this time, and rise to that height immediately at the gateways. These walls are composed of the common soil, which seems to have been taken up from no particular spot, but uniformly from near the surface. That part of this work which is square, has eight gateways; the sides of this square are sixty-six rods in length, containing an area of twenty-seven acres and two tenths. This part of the work has three gateways, connecting it with the larger one; one of which is between two parallel walls about four feet high. A small rivulet, rising towards the southwest side of the larger part of the largest work, runs through the wall, and sinks into the earth at w, s. Some suppose this sink hole to have been a work of art, originally. It is fifteen feet deep, and thirty-nine across it, at the surface. There are two mounds, the one within, and the other just outside of this work, represented by m, m; the latter is twenty feet high at this time.

Works at A, are all connected as represented in the plate. Their several contents will be seen by referring to it. The square work, it will be seen, contains exactly the same area [pg 52] with the square one belonging to B, and is, in all other respects, so much like that work, that to describe this, would be to repeat what has been said concerning the former. Such coincidences are very common in our ancient works; so that a correct description of one applies to hundreds in different parts of the country.

There is no mound within its walls, but there is one about ten feet high, nearly one hundred rods to the west of it. The large irregular part of the larger work, contains, as will be seen, seventy-seven acres and one-tenth, in the walls of which are eight gateways, besides the two leading into the square just described. These gateways are from one to six rods in width, differing in that respect, very much, one from another. Connected by a gateway with this large work, is another in the northwest, sixty poles in diameter. In its center is another circle, whose walls are now about four feet high, and this lesser circle six rods in diameter. There are three ancient wells at w, w, w, one of which is on the inside, the others on the outside of the wall. As the drawing shows, within the large work of irregular form, are two elevations, which are elliptical. The largest one is near the center; its elevation is twenty-five feet; its longest diameter is twenty rods; its shortest, ten rods; its area is nearly one hundred and fifty-nine square rods. This work is composed mostly of stones, in their natural state. They must have been brought from the bed of the creek, or from the hill. This elevated work is full of human bones. Some have not hesitated to express a belief, that on this work human beings were once sacrificed.

The other elliptical work has two stages; one end of it is only about eight feet high, the other end is fifteen. The surfaces of both are smooth. Such works are not as common here as on the Mississippi, and they are more common still further south, in Mexico.

There is a work in form of a half moon, set round the edges with stones, such as are now found about one mile [pg 53] from the spot from whence they were probably brought. Near this semicircular work is a very singular mound, five feet high, thirty feet in diameter, and composed entirely of a red ocher, which answers very well as a paint. An abundance of this ocher is found on a hill not a great distance from this place; and from this circumstance, the name of the fine stream in the vicinity, in all probability, is derived. It is called "Paint creek."

The wells already mentioned, may be thus described. They are very broad at the top, one of them is six rods, another, four; the former is now fifteen feet in depth; the latter, ten. There is water in them, and they are like the one at Marietta, described by Dr. Hildreth. Near the limestone road, are several such ones.

The most interesting work, represented on the plate by C, remains to be noticed. It is situated on a high hill, believed to be more than three hundred feet in height, which is in many places almost perpendicular. The walls of this consist of stones in their natural state. This wall was built upon the very brow of this hill, almost all around, except at D, where the ground is level. It had originally two gateways, at the only places where roads could be made to the interval below. At the northern gateway, stones enough now lie to have built two considerable round towers. From thence to the creek is a natural, perhaps there was one an artificial, road. The stones lie scattered about in confusion, and consist mostly of what McClure would call the old red sand stone, taken from the sides of the hill on which this "walled town" once stood. Enough of these stones lie here, to have furnished materials for a wall four feet in thickness, and ten feet in height. On the inside of the wall, at line D, there appears to have been a row of furnaces or smiths' shops, where the cinders now lie many feet in depth.

I am not able to say with certainty, what manufactures were carried on here, nor can I say whether brick or iron tools were made here, or both. It was clay that was exposed [pg 54] to the action of fire; the remains are four or five feet in depth, even now, at some places. Iron ore, in this country, is sometimes found in such clay; brick and potters' ware are manufactured out of it, in some other instances. This wall encloses an area of one hundred and thirty acres. It was one of the strongest places in this state, from its situation, so high is its elevation, so nearly perpendicular are the sides of the hill on which it stood.

The courses of the wall correspond with those of the very brow of the hill; and the quantity of stones is the greatest on each side of the gateways, and at any turn in the course of the wall, as if towers and battlements had been here erected. If the works at A and B, had been "sacred enclosures," this was the strong military work which defended them. No military man could have selected a better position for a place of protection to his countrymen, their temples, their altars, and gods.

In the bed of Paint creek, which washes the foot of the hill on which the "walled town" stood, are four wells, worthy of our notice. They were dug through a pyritous slate rock, which is very rich in iron ore. When first discovered by a person passing over them in a canoe, they were covered over, each, by a stone, of about the size, and very much in the shape, of the common millstone, now in use in our grist mills. These covers had a hole through their center, through which a large pry or handspike might be put, for the purpose of removing them off and on the wells. The hole through the center was about four inches in diameter. The wells at the top were more than three feet in diameter, and stones well wrought with tools, so as to make good joints, as a stone mason would say, were laid around the several wells.

I had a good opportunity to examine these wells, the stream in which they are sunk being very low. The covers are now broken to pieces, and the wells filled with pebbles. That they are works of art, is beyond a doubt. For what purpose they were dug, has been a question among those [pg 55] who have visited them, as the wells themselves are in the stream. The bed of the creek was not here, in all probability, when these were sunk. These wells, with stones at their mouths, resemble those described to us in the patriarchial ages. Were they not dug in those days?

At E, is a circular work containing between seven and eight acres, whose walls are not now more than ten feet high, surrounded with a ditch, except at one place, perhaps four rods broad, where there is an opening much resembling a modern turnpike road, leading down into the interval land, adjoining the creek. At the end of the ditch, adjoining the wall on each side of this road is a spring of very good water. Down to the largest one is the appearance of an ancient road. These springs were dug down considerably, or rather the earth where they now rise, by the hand of man.

General William Vance's dwelling house now occupies this gateway; and his orchard and fruit yard, the area within this ancient, sacred enclosure.

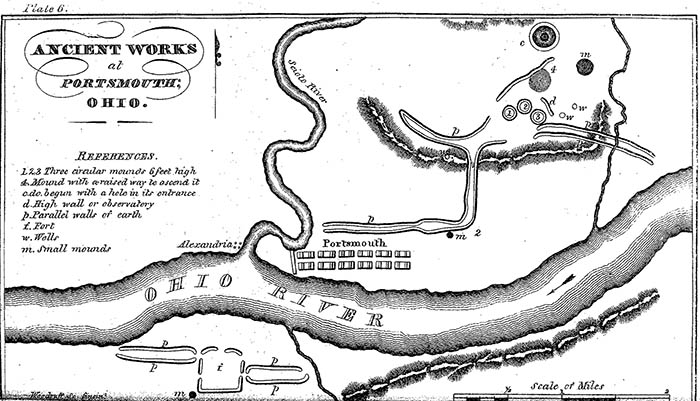

ANCIENT WORKS AT PORTSMOUTH, OHIO.

Descending the Scioto to its mouth, at Portsmouth, we find an ancient work, which I doubt not was a military one of defense, situated on the Kentucky shore, nearly opposite the town of Alexandria. The reader is referred to the accurate drawing of all the works near this place, taken on the spot, from actual examination and survey. The importance of this place, it seems, was duly appreciated the people who, in "olden time," resided here. To their attachment to this part of the country, as well as the great population which must have been here, are we indebted for the striking and numerous traces of a once flourishing settlement.

The annexed plate will enable the reader to form a very correct idea of these ancient remains.

On the Kentucky side of the Ohio, opposite the mouth of the Scioto river, is a large fort, with an elevated, large mound of earth near its southwestern outside angle, and parallel walls of earth, as represented by p, p, p, p. The eastern parallel walls have a gateway leading down a high steep bank of a river to the water. They are about ten rods asunder, and from four to six feet in height at this time, and connected with the fort by a gateway. Two small rivulets have worn themselves channels quite through these walls, from ten to twenty feet in depth, since they were deserted, from which their antiquity may be inferred.

The fort is represented by F, on the plate, which is nearly a square, with five gateways, whose walls of earth are now from fourteen, to twenty feet in height.

From the gateway, at the northwest corner of this fort, commenced two parallel walls of earth, extending nearly to [pg 59] the Ohio, in a bend of that river, where, in some low ground near the bank, they disappear. The river seems to have moved its bed a little since these walls were thrown up. A large elevated mound at the southwest corner of the fort, on the outside of the fortification, is represented by m. It appears not to have been used as a place of sepulture; it is too large to have belonged to that class of antiquities. It is a large work, raised perhaps twenty feet or more, very level on its surface, and I should suppose contains half an acre of ground. It seems to me to have been designed for uses similar to the elevated squares at Marietta. Between these works and the Ohio, is a body of fine interval lands, which was nearly enclosed by them; aided by the river, and a creek, which has high perpendicular banks. Buried in the walls of this fort, have been found and taken out, large quantities of iron, manufactured into pickaxes, shovels, gun barrels, &c., evidently secreted there by the French, when they fled from the victorious and combined forces of England and America, at the time fort Du Quesne, afterwards fort Pitt, was taken from them. Excavations made in quest of these hidden treasures, are to be seen on these walls, and in many other places near them.

Several of their graves have been opened and articles found, which leave no doubt on my mind as to their authors, nor any great doubt as to the time when they were deposited here.

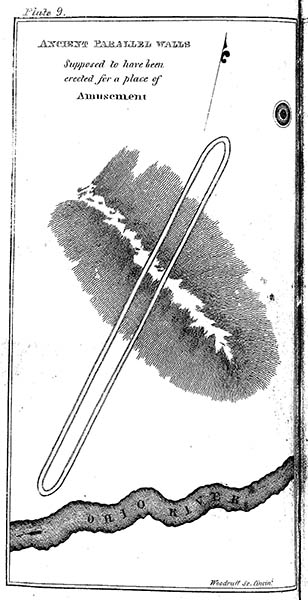

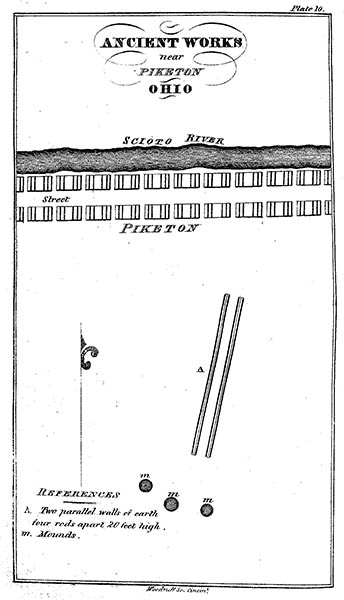

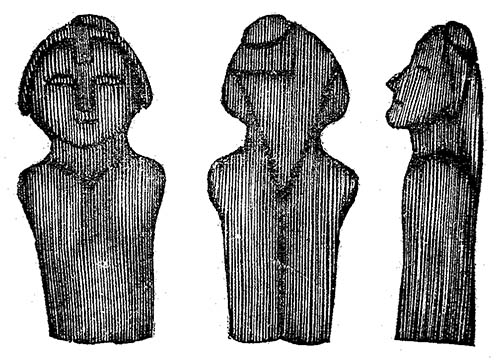

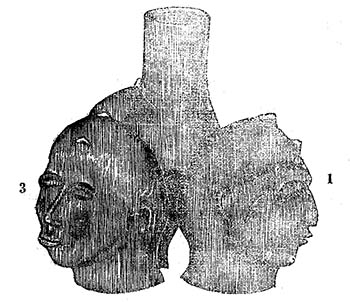

On the north side of the river, are works still more extensive than these, more intricate, and of course, more impressive. We must again refer to the plate, in order to shorten our labor in description, and at the same time, give a clearer idea of them than could otherwise be obtained.