The Way of an Indian

by Frederic Remington

The Bat Devises Mischief Among the Yellow-Eyes

White Otter the boy had been superseded by the man with the upright eagle-feather, whom people now spoke of as Ho-to-kee-mat-sin, the Bat. The young women of the Chis-chis-chash threw approving glances after the Bat as he strode proudly about the camp. He was possessed of all desirable things conceivable to the red mind. Nothing that ever bestrode a horse was more exquisitely supple than the well-laid form of this young Indian man; his fame as a hunter was great, but the taking of the Absaroke scalp was transcendent. Still, it was not possible to realize any matrimonial hopes which he was led to entertain, for his four ponies would buy no girl fit for him. The captured war-pony, too, was one of these, and not to be transferred for any woman.The Bat had conjured with himself and conceived the plan of a trip to the far south--to the land of many horses--but the time was not yet.

As the year drew on, the Chis-chis-chash moved to the west--to the great fall buffalo-hunt--to the mountains where they could gather fresh tepee-poles, and with the hope of trade with the wandering trapper bands. To be sure, the Bat had no skins of ponies to barter with them, but good fortune is believed to stand in the path of every young man, somewhere, some time, as he wanders on to meet it. Delayed ambition did not sour the days for the Indian. He knew that the ponies and the women and the chieftainship would come in the natural way; besides which, was he not already a warrior worth pointing at?

He accompanied the hunters when they made the buffalo-surround, where the bellowing herds shook the dusty air and made the land to thunder while the Bat flew in swift spirals like his prototype. Many a carcass lay with his arrows driven deep, while the squaws of Big Hair's lodge sought the private mark of the Bat on them.

The big moving camp of the Chis-chis-chash was strung over the plains--squaws, dogs, fat little boys toddling after possible prairie dogs, tepee ponies, pack-animals with gaudy squaw trappings, old chiefs stalking along in their dignified buffalo-robes--and a swarm of young warriors riding far on either side.

The Bat and Red Arrow's lusty fire had carried them far in the front, and as they slowly raised the brow of a hill they saw in the shimmer of the distance a cavalcade with many two-wheeled carts--all dragging wearily over the country.

"The Yellow-Eyes!" said the Bat.

"Yes," replied Red Arrow. "They always march in the way the wild ducks fly--going hither and yon to see what is happening in the land. But their medicine is very strong; I have heard the old men say it."

"Hough! it may be, but is not the medicine of the Chis-chis-chash also strong? Why do we not strike them, Red Arrow? That I could never understand. They have many guns, blankets, paints, many strong ponies and the strong water, which we might take," added the Bat, in perplexity.

"Yes, true, we might take all, but the old men say that the Yellow-Eyes would not come again next green grass--we would make them afraid. They would no more bring us the powder and guns or the knives. What could we do without iron arrow-heads? Do you remember how hard it was to make bone arrowheads, when we were boys and could not get the iron? Then, the Yellow-Eyes are not so many as the Chis-chis-chash, and they are afraid of us. No, we must not make them more timid," replied the wise Red Arrow.

"But we may steal a gun or a strong pony, when they do not look," continued the indomitable Bat.

"Yes--we will try."

"I will go down the hill, and make my pony go around in a circle so that the camp may send the warriors out to us," saying which, the Bat rode the danger-signal, and the Chis-chis-chash riders came scurrying over the dry grass, leaving lines of white dust in long marks behind them. Having assembled to the number of a hundred or so, the chiefs held a long consultation, each talking loudly from his horse, with many gestures. After some minutes, the head war-chief declared in a high, rough voice that the man must go to the Yellow-Eyes with the peace-sign, and that they must not do anything to make the Yellow-Eyes afraid. The white men had many guns, and if they feared the Indians they would fire on them, and it would be impossible to get near the powder and paints and knives which were in the carts.

The warriors took each from a little bag his paints and plumes. Sitting in the grass, they decorated themselves until they assumed all hues--some red, and others half white or red across the face, while the ponies came in for streaks and daubs, grotesque as tropic birds.

So over the hill rode the line of naked men, their ponies dancing with excitement, while ahead of them a half-breed man skimmed along bearing a small bush over his head. The cavalcade of the Yellow-Eyes had halted in a compact mass, awaiting the oncoming Indians. They had dismounted and gone out on the sides away from the carts, where they squatted quietly in the grass. This was what the Yellow-Eyes always did in war, unlike Indians, who diffused themselves on their speeding ponies, sailing like hawks.

A warrior of the Yellow-Eyes came to meet them, waving a white cloth from his gun-barrel after the manner of his people, and the two peace-bearers shook hands. Breaking into a run, the red line swept on, their ponies' legs beating the ground in a vibratory whirl, their plumes swishing back in a rush of air, and with yelps which made the white men draw their guns into a menacing position.

At a motion of the chief's arm, the line stopped. The Yellow-Eyed men rose slowly from the grass and rested on their long rifles, while their chief came forward.

For a long time the two head men sat on their ponies in front of the horsemen, speaking together with their hands. Not a sound was to be heard but the occasional stamp of a pony's hoof on the hard ground. The beady eyes of the Chis-chis-chash beamed malevolently on the white chief--the blood-thirst, the warrior's itch, was upon them.

After an understanding had been arrived at, the Indian war-chief turned to his people and spoke. "We will go back to our village. The Yellow-Eyes do not want us among their carts--they are afraid. We will camp near by them to-night, and tomorrow we will exchange gifts. Go back, Chis-chis-chash, or the white chief says it is war. We do not want war." This and much more said the chief and his older men to the impulsive braves, whose uncontrollable appetites had been whetted by the sight of the carts. The white man was firm and the Indians drew off to await the coming of the village.

The two camps were pitched that night two miles apart; the Yellow-Eyes intrenched behind their packs and carts, while the Indians, being in overwhelming strength, did much as usual, except that the camp-soldiers drove the irrepressible boys back, not minding to beat their ponies with their whips when they were slow to go. There was nothing that a boy could do except obey when the camp-soldier spoke to him. He was the one restraint they had, the only one.

But as a mark of honor, the Bat and Red Arrow were given the distinguished honor of observing the Yellow-Eyed camp all night, to note its movements if any occurred, and with high hearts they sat under a hill-top all through the cold darkness, and their souls were much chastened by resisting the impulses to run off the white man's ponies, which they conceived to be a very possible undertaking. The Bat even declared that if he ever became a chief this policy of inaction would be followed by one more suited to pony-loving young men.

Nothing having occurred, they returned before daylight to their own camp so to inform the war-chief.

That day the Chis-chis-chash crowded around the barricade of the Yellow-Eyes, but were admitted only a few at a time. They received many small presents of coffee and sugar, and traded what ponies and robes they could. At last it became the time for the Bat to go into the trappers' circle. He noted the piles of bales and boxes as he passed in, a veritable mountain of wealth; he saw the tall white men in their buckskin and white blanket suits, befringed and beribboned_,_ their long, light hair, their bushy beards, and each carrying a well-oiled rifle. Ah, a rifle! That was what the Bat wanted; it displaced for the time all other thoughts of the young warrior. He had no robes and came naked among the traders--they noted him--only an Indian boy, and when all his group had bartered what they had, the half-breed who had rode with the peace branch spoke to him, interpreting:

"The white chief wants to know if you want to buy anything."

"Yes. Tell the white chief that I must have a gun, and some powder and ball."

"What has the boy to give for a gun?" asked a long-bearded leader.

"A pony--a fast buffalo-pony," replied our hero through the half-breed.

"One pony is not enough for a gun; he must give three ponies. He is too young to have three ponies," replied the trader.

"Say to the Yellow-Eye that I will give him two ponies," risked the Bat.

"No, no; he says three ponies, and you will not get them for less. The white chief means what he says. He says you must leave here now with those people so that older men can come and trade."

"Let me see the gun," demanded the boy. A gun was necessary for the Bat's future progression.

A subordinate was directed to show a gun to him, which he did by taking him one side and pulling one from a cart. It was a long, yellow-stocked smoothbore, with a flintlock. It had many brass tacks driven into the stock, and was bright in its cheap newness. As the Bat took it in his hand he felt a nervous thrill, such as he had not experienced since the night he had pulled the dripping hair from the Absaroke. He felt it all over, smoothing it with his hand; he cocked and snapped it; and the little brown bat on his scalp-lock fairly yelled: "Get your ponies, get your ponies--you must have the gun."

Returning the gun, the Bat ran out, and after a time came back with his three ponies, which he drove up to the white man's pen, saying in Chis-chis-chash: "Here are my ponies. Give me the gun."

The white chief glanced at the boy as he sat there on a sturdy little clip-maned war-pony--the one he had stolen from the Absaroke. He spoke, and the interpreter continued: The trader says he will take the pony you are riding as one of the three."

"Tell him that I say I would not give this pony for all the goods I see. Here are my three ponies; now let him give me the gun before he makes himself a liar," and the boy warrior wore himself into a frenzy of excitement as he yelled: "Tell him if he does not give me the gun he will feel this war-pony in the dark, when he travels; tell him he will not see this war-pony, but he will feel him when he counts his ponies at daylight. He is a liar."

"The white chief says he will take the war-pony in place of three ponies, and give you a gun, with much powder and many balls."

"Tell the Yellow-Eye he is a liar, with the lie hot on his lips," and the Bat grew quiet to all outward appearance.

After speaking to the trader, the interpreter waved at the naked youth, sitting there on his war-pony: "Go away--you are a boy, and you keep the warriors from trading."

With a few motions of the arms, so quickly done that the interpreter had not yet turned away his eye, the Bat had an arrow drawn to its head on his leveled bow, and covering the white chief.

Indians sprang between; white men cocked their rifles; two camp-soldiers rushed to the enraged Bat and led his pony quietly away, driving the three ponies after him.

|

| "The interpreter waved at the naked youth, sitting there on his war-pony." |

The Chis-chis-chash were busy during the ensuing days following the buffalo, and their dogs grew fat on the leavings of the carcasses. The white traders drew their weary line over the rolling hills, traveling as rapidly as possible to get westward of the mountains before the snows encompassed them. But by night and by day, on their little flank in rear or far in front, rode two vermilion warrior-boys, on painted ponies, and one with an eagle-plume upright in his scalp-lock. By night two gray wolves stood upward among the trees or lay in the plum-branches near enough to see and to hear the Iving talk of the Yellow-Eyes.

Old Delaware hunters in the caravan told the white chief that they had seen swift pony-tracks as they hunted through the hills; and that, too, many times. The tracks showed that the ponies were strong and went quickly--faster than they could follow on their jaded mounts. The white chief must not trust the solitude.

But the trailing buffalo soon blotted out the pony-marks; the white men saw only the sailing hawks, and heard only bellowing and howling at night. Their natures responded to the lull, until two horse-herders, sitting in the willows, grew eager in a discussion, and did not notice at once that the ponies and mules were traveling rapidly away to the bluffs. When the distance to which the ponies had roamed drew their attention at last, they looked hard and put away their pipes and gathered up their ropes. Two ponies ran hither and thither behind the horses. There was method in their movements--were they wild stallions? The white men moved out toward the herd, still gazing ardently; they saw one of these ponies turn quickly, and as he did so a naked figure shifted from one side to the other of his back.

"Indians! Indians!"

A pistol was fired--the herders galloped after.

The horse-thieves sat up on their ponies, and the long, tremulous notes of the war-whoop were faintly borne on the wind to the camp of the Yellow-Eyes. Looking out across the plains, they saw the herd break into a wild stampede, while behind them sped the Bat and Red Arrow, waving long-lashed whips, to the ends of which were suspended blown-up buffalo-bladders, which struck the hard ground with sharp, explosive thumps, rebounding and striking again. The horses were terrorized, but, being worn down, could not draw away from the swift and supple war-steeds. There were more than two hundred beasts, and the white men were practically afoot.

Many riders joined the pursuit; a few lame horses fell out of the herd and out of the race--but it could have only one ending with the long start. Mile by mile the darkness was coming on, so that when they could no longer see, the white pursuers could hear the beat of hoofs, until that, too, passed--and their horses were gone.

That night there was gloom and dejection around the camp-fires inside the ring of carts. Some recalled the boy on the war-pony with the leveled bow; some even whispered that Mr. McIntish had lied to the boy, but no one dared say that out loud. The factor stormed and damned, but finally gathered what men he could mount and prepared to follow next day.

Follow he did, but the buffalo had stamped out the trail, and at last, baffled and made to go slow by the blinded sign, he gave up the trail, to hunt for the Chis-chis-chash village, where he would try for justice at the hands of the head men.

After seven days' journey he struck the carcasses left in the line of the Indians' march, and soon came up with their camp, which he entered with appropriate ceremony, followed by his retinue--half-breed interpreter, Delaware trailers, French horse-herders, and two real Yellow-Eyed men--white Rocky Mountain trappers.

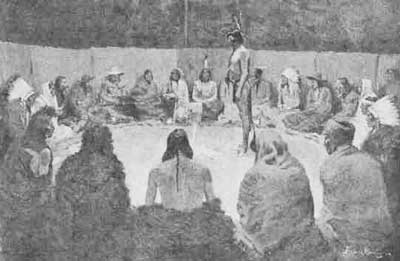

He sought the head chief, and they all gathered in the council tepee. There they smoked and passed the pipe. The squaws brought kettles of buffalo-meat, and the eager youngsters crowded the door until a camp-soldier stood in the way to bar them back. The subchiefs sat in bronze calm, with their robes drawn in all dignity about them.

When all was ready, Mr. McIntish stood in the middle of the lodge and spoke with great warmth and feeling, telling them that Chis-chis-chash warriors had stolen his horse-herd--that he had traced it to their camp and demanded its return. He accused them of perfidy, and warned them that from thence on no more traders would ever come into their country, but would give their guns to the Absaroke, who would thus be able to overwhelm them in war. No more would the chiefs drink of the spring-water they loved so well--no more would a white man pass the pipe with the Chis-chis-chash if justice was not done; and much more which elicited only meaningless grunts from the stoic ring of listeners.

When he had finished and sat down, the head chief arose slowly, and stepping from the folds of his robe, he began slowly to talk, making many gestures. "If the white chief had tracked the stolen ponies to his camp, let him come out to the Indian pony-herds and point them out. He could take his horses."

The face of the trader grew hard as he faced the snare into which the chief had led him, and the lodge was filled with silence.

The camp-soldier at the entrance was brushed aside, and with a rapid stride a young Indian gained the center of the lodge and stood up very straight in his nakedness. He began slowly, with senatorial force made fierce by resolve.

"The white chief is a liar. He lied to me about the gun; he has come into the council tepee of the Chis-chis-chash and lied to all the chiefs. He did not trail the stolen horses to this camp. He will not find them in our pony-herds."

He stopped awaiting the interpreter. A murmur of grunts went round.

"I--the boy--I stole all the white chief's ponies, in the broad daylight, with his whole camp looking at me. I did not come in the dark. He is not worthy of that. He is a liar, and there is a shadow across his eyes. The ponies are not here. They are far away--where the poor blind Yellow-Eyes cannot see them even in dreams. There is no man of the Chis-chis-chash here who knows where the horses are. Before the liar gets his horses again, he will have his mouth set on straight," and the Bat turned slowly around, sweeping the circle with his eyes to note the effect of his first speech, but there was no sound.

Again the trader ventured on his wrongs--charged the responsibility of the Bat's actions on the Chis-chis-chash, and pleaded for justice.

The aged head chief again arose to reply, saying he was sorry for what had occurred, but he reminded McIntish that the young warrior had convicted him of forged words. What would the white chief do to recompense the wrong if his horses were returned? He also stated that it was not in his power to find the horses, and that only the young man could do that.

Springing again to his feet, with all the animation of resolution, the Bat's voice clicked in savage gutturals. "Yes, it is only with myself that the white liar can talk. If the chiefs and warriors of my tribe were to take off my hide with their knives--if they were to give me to the Yellow-Eyes to be burnt with fire--I could not tell where the ponies lie hidden. My medicine will blind your eyes as does the north wind when he comes laden with snow.

"I will tell the white man how he can have his ponies back. He can hand over to me now the bright new gun which lies by his side. It is a pretty gun, better than any Indian has. With it, his powder-horn and his bullet-bag must go.

|

| "I will tell the white man how he can have his ponies back." |

The boy warrior stood with arms dropped at his sides, very straight in the middle of the tent, the light from the smoke hole illuminating the top of his body, while his eye searched the traders.

McIntish gazed through his bushy eyebrows at the victor. His burnt skin turned an ashen-green; his right hand worked nervously along his gun-barrel. Thus he sat for a long time, the boy standing quietly, and no one moved in the lodge.

With many arrested motions, McIntish raised the rifle until it rested on its butt; then he threw it from himself, and it fell with a crash across the dead ashes of the fire, in front of the Bat. Stripping his powder-horn and pouch off his body, violently he flung them after, and the Bat quickly rescued them from among the ashes. Gathering the tokens and girding them about his body, the Bat continued: "If the white liar will march up this river one day and stop on the big meadows by the log house, which has no fire in it; if he will keep his men quietly by the log house, where they can be seen at all times; if he will stay there one day, he will see his ponies coming to him. I am not a boy; I am not a man with two tongues; I am a warrior. Go, now--before the camp-soldiers beat you with sticks."