|

| Hopewell Copper Breastplate. |

|

| Hopewell Copper Bird. |

|

| Raven Effigy Pipe. |

Beginning in the late 1700s, settlers from the eastern states migrating to the Ohio Valley found hundreds of mounds and earthworks. The Shawnee and other American Indian peoples of the region apparently knew nothing of the builders. Many tried to solve the mystery of the mounds. Some thought that the mound builders must be a "lost race" who vanished before the Indians of historic times arrived.

In the 1840s Ephraim G. Squier, a Chillicothe newspaper editor, and Edwin H. Davis, a Chillicothe physician, systematically mapped the mounds and documented what was found inside them. The Smithsonian Institution published Squier and Davis's findings in the 1848 Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley. The Hopewell peoples–American Indians who lived between 2,200 and 1,500 years ago–were recognized as the architects and builders of the mounds.

The Hopewell were named for Capt. Mordecai Hopewell, who owned the farm where part of an extensive earthwork site was excavated in 1891. The Hopewell settled along riverbanks in present-day Ohio and in other regions between the Great Lakes and the Gulf of Mexico. Excavations of dwelling sites show that they made their living by hunting, gathering, farming, and trading.

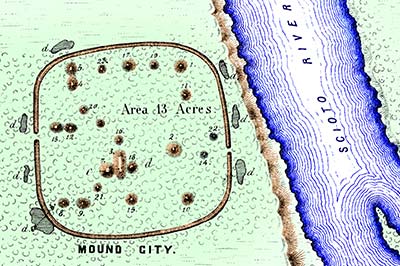

No one lived at the earthworks; artifacts found inside reveal that the mounds were built primarily to cover burials. A mound was typically built in stages: A wooden structure containing a clay platform was probably the scene of funeral ceremonies and other gatherings. The dead were either cremated or buried onsite. Objects of copper, stone, shell, and bone were placed near the remains. After many such ceremonies the structure was burned or dismantled, and the entire site was covered with a large mound of earth. Wall-like earthworks sometimes surrounded groups of mounds. Squier and Davis named on site Mound City because of its unusual concentration of mounds, at least 23, encircled by a low earthen wall. During World War 1, Mound City was covered by part of an Army training facility, Camp Sherman, and many of the mounds were destroyed. The Ohio Historical and Archeological Society conducted excavation and restoration work in 1920-21. In 1923 the Mound City Group was declared a national monument.

The National Park Service conducted additional excavations in the 1960s and '70s. In 1992, Mound City Group became Hopewell Culture National Historic Park, which also includes four other sites in the region: High Bank Works, Hopeton Earthworks, Hopewell Mound Group, and Seip Earthworks. When you visit the grounds of Mound City, remember that although we know of the Hopewell peoples primarily through the way they memorialized their dead, their world was very much alive.

An excellent introduction to the Mound Builders can be found in the 1879 publication The Mound Builders, by J. P. MacLEAN.