The Gettysburg Address

When the armies marched away from Gettysburg they left behind a community in shambles and more than 51,000 killed, wounded, and missing soldiers. Wounded and dying were crowded into nearly every building. Most of the dead lay in hastily dug and inadequate graves; some had not been buried at all.

This situation so distressed Pennsylvania's governor, Andrew Curtin, that he commissioned a local attorney, David Wills, to purchase land for a proper burial ground for Union dead. Within four months of the battle, reinterment began on 17 acres that became Gettysburg National Cemetery.

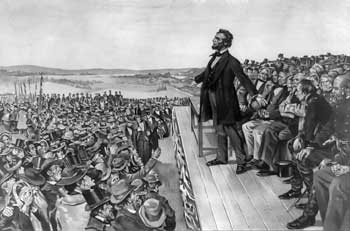

The cemetery was dedicated on November 19, 1863. The principal speaker, Edward Everett, delivered a well-received two-hour oration rich in historical detail and classical allusion. He was followed by President Abraham Lincoln, who had been asked to make "a few appropriate remarks."

Lincoln's speech, which contains 272 words and took about two minutes to deliver, is considered a masterpiece of the English language. It transformed Gettysburg from a scene of carnage into a symbol, giving meaning to the sacrifice of the dead and inspiration to the living. "I should be glad," Everett told Lincoln, "if I…came as near to the central idea of the occasion, in two hours, as you did in two minutes."

Contrary to popular belief, Lincoln did not write the speech on the back of an envelope during the trip to Gettysburg, but took great pains in its formulation. He composed the first draft in Washington shortly before November 18 and revised it at the home of David Wills in Gettysburg sometime before the dedication.

The second draft, written in ink on two pages of the same paper used for part of the first draft, reflects Lincoln's first revision of the address and, except for the words "under God," constitutes the text of the speech delivered at the dedication ceremony.

Less than half the Union battle dead finally interred in the national cemetery had been removed from their field graves by the day of the dedication. Within a few years, however, the bodies of more than 3,500 Union soldiers killed in the battle had been reinterred in the cemetery and the landscaping completed. Following the war the remains of 3,320 Confederate soldiers were removed from the battlefield to cemeteries in the South.

Abraham Lincoln's Address

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this

continent a new nation, conceived in liberty and dedicated to the

proposition that all men are created equal.

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this

continent a new nation, conceived in liberty and dedicated to the

proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation or any nation so conceived and so dedicated can long endure. We are met on a great battlefield of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field as a final resting-place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this. But in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate, we cannot consecrate, we cannot hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead who struggled here have consecrated it far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here.

It is for us the living rather to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us--that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion--that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain, that this nation under God shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people, by the people, for the people shall not perish from the earth.