Of all of the events that occurred during the three days of the Battle of Gettysburg, few have been more studied, debated, celebrated, and romanticized than Longstreet's Assault, more popularly known as "Pickett's Charge". Coordinated by Lt. General James Longstreet, the attack has been referred to as "Longstreet's Grand Assault" by many historians. Yet it is General George Pickett's name that has forever been attached to the "High Water Mark" of the battle, for his troops- "the flower of Virginia manhood"- were more glorified for their participation in the charge by southern and northern writers in the years following the battle.

The names of the places associated with the charge are deeply indented on the American conscience. Every summer, "The Angle" and "The High Water Mark" are crowded with visitors who come to commemorate the event and ponder those terrible minutes when American killed American in a desperate contest of wills and ideals. So much carnage in such a small place- it is difficult for us today to realize the horror those young men faced, and how quickly the hopes of the North and South were determined in this famous battle.

View of the Angle in 1870 The High Water Mark and Angle in 1870-72. This view from the Emmitsburg Road shows the ground over which Garnett's brigade charged to reach the Angle and Cushing's guns. (Gettysburg NMP)

Pickett's Division was one of the largest in the Army of Northern Virginia. Having been assigned to defenses in the Richmond area in 1863, Pickett's troops were veterans of several campaigns and joined the army as it made its way toward Maryland and Pennsylvania. Pickett was anxious that he would not get to see any of the fighting during the campaign and was "filled with excitement" when he was ordered to move his three brigades to the front lines on the morning of July 3rd. With all preparations completed, Pickett's soldiers marched across the shell-swept field, temporarily broke the Union line, and returned to Seminary Ridge, broken and shattered. The charge had lasted barely 50 minutes, but Pickett's Virginians had achieved a remarkable high point of honor and glory in southern heritage and the story of Gettysburg. Pickett lost over one half of his division in killed, wounded, and captured including all three of his brigadier generals in the charge. It was ironic to some that with so much destruction in the ranks and among the high-ranking officers, General Pickett escaped the battle without a scratch. (The general's location during the charge would later become a heated debate among some of the participants.) The fate of his three generals was each very different from the other:

|

| Richard Brooke Garnett |

|

| James Kemper |

|

| Lewis Armistead |

As for General Pickett, he did not enjoy great success as a field commander after Gettysburg. Distraught over the losses in his command, Pickett led his troops back to Virginia where the weariness of the harsh campaign eventually wore off and his spirits were rejuvenated with the return of Corse's Brigade to his division. That fall Pickett was assigned to command the Department of Virginia and North Carolina during which time he took a short leave of absence to marry his third and most adoring wife, LaSalle Corbell. The couple eventually had two children. General Pickett's duties placed him in command of numerous defensive lines around Richmond, Petersburg, and southeast Virginia, a post he held until 1864 when he returned to the field in command of his old division.

On April 1, 1865, Pickett was in command of Confederate troops placed at the strategic crossroads of Five Forks, Virginia, several miles west of Petersburg. That morning, General Pickett accepted an invitation to attend a shade bake picnic with fellow officers along the banks of Hatcher's Run, at a site far behind the front lines and out of touch with their men. Shortly after 4 PM, a combined force of Union infantry and cavalry stormed the Southern position and broke through the thin line. Pickett raced to the front but it was too late. His command was in a shambles and despite the efforts of his brigade officers to stave off the Union assault, there was little he could do but rally the survivors and withdraw from the battlefield. With Five Forks in Union hands, the last supply route into Petersburg was lost and the city was forced to be abandoned.

|

|

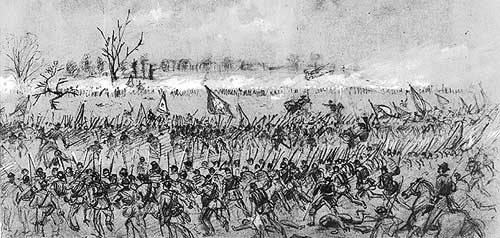

Battle of Five Forks

Charge of the Fifth Corps on Pickett's troops at Five Forks, April 1, 1865 |

Pickett's absence from the front line at Five Forks possibly inflamed the ire of General Lee, who had ordered Five Forks to be held at all costs. The Army of Northern Virginia retreated from the Richmond and Petersburg lines and moved west toward Danville, Virginia, hotly pursued by two Union armies and a massive cavalry force. On April 6 at Saylor's Creek, Virginia, Pickett's command, along with troops under Generals R.H. Anderson, Richard Ewell, and Joseph Kershaw, was nearly encircled by a combined force of Union cavalry and infantry. An attempt to break out failed and the Confederate position folded, costing Lee over one-third of his army. Only several hundred panicked Confederates were able to get out of the trap and they were personally rallied by General Lee. General Pickett and his staff narrowly escaped capture as night fell. Pickett's escape without bringing out his troops may have been the final straw for Lee who relieved Generals Anderson, Bushrod Johnson, and Pickett of command two days later, though Lee's order evidently never reached Pickett in the confusion of the retreat. The general remained with his division as the army wearily marched to Appomattox Court House, where he formally surrendered and bade goodbye to the soldiers of his old command.

General Pickett returned to Richmond where he was faced with monumental decisions of providing for his family. He attempted farming for several years before he finally accepted work with an insurance company based in New York. As an agent for the company, Pickett sold policies from his home in Richmond and worked with insurance agents in other Virginia cities from whom he drew a commission. The life of an insurance agent was distasteful to the man who once led thousands of soldiers into battle, but he continued to work with the company to support his family until his death in 1875.

In a journalistic sense, the charge at Gettysburg was to be General Pickett's most important contribution to the southern cause. Southern writers heralded his Virginians who made the attack against impossible odds, one writer placing the general in the role of a tragic hero who did what he could despite the mistakes and miscalculations of others. Controversies surrounding his actions during the Appomattox Campaign did not directly affect the general who was held in high regard by the officers and men who served under him. Apparently embittered by the destruction of his division at Gettysburg and uneasy with the awkward relationship with his former army commander, Pickett chose not to openly discuss his career as a Confederate officer or what happened on that fateful July afternoon in Pennsylvania. Yet the general never reconciled the losses his command suffered at Gettysburg, and never forgave Lee for ordering so many of his young Virginians into the last great charge that today bears his name.

The charge was not without controversy even before it began, and the debate as to the assault's merits have been argued over and over again ever since. Questions quickly arose soon after the battle as to who was responsible for the failure. A few unnamed sources who favored the Virginians blamed the disaster on the lack of support from Pettigrew's and Trimble's columns, criticisms that first appeared in newspapers in the fall of 1863. The accusations caused hard feelings between commands and served no purpose other than to confuse facts surrounding the charge. After the war, the conflict took a more personal side when a number of writers accused the North Carolinians of Pettigrew's division of cowardice and not going into the charge as they were "untried and green troops", a complete falsehood. The debate grew more bitter as time passed as more and more writers looked to Gettysburg as the turning point of the war in southern fortunes. The arguments had cooled some by the turn of the century. But in 1903, Samuel A. Ashe, a North Carolina writer, wrote a scathing article published in a Richmond newspaper in which he demanded to know why North Carolina troops were continually slandered by Virginia veterans. He also broached the subject of Pickett's whereabouts during the attack, blaming the failure of the charge on the general for his lack of command. The flame became an inferno as former staff officers rushed to Pickett's defense. Cruel innuendo followed including a condemning statement attributed to Pickett, that had no factual base. Yet the hard feelings did not easily pass away and the bitter debate resurfaced again and again until the last veteran of the charge passed away. Interestingly enough, only one or two southern writers ever gave the Union defenders of Cemetery Ridge any credit for breaking up the attack. The southern spirit of invincibility did not die during the Civil War after all.

The culmination of Lee's last hopes for victory in Pennsylvania, "Pickett's Charge" was thwarted by a number of factors including poor staff work, superior organization and control of Union artillery, massed infantry lines against rifled weapons, and a Pennsylvania brigade standing on their native soil in the Angle that fought for every inch of ground. The Philadelphia Brigade was composed of regiments raised in the city and counties surrounding Philadelphia. The celebrated brigade was first led by Colonel Edward Baker and fought under several different commanders through the terrible campaigns of 1862 and 1863. New York-born Brigadier General Alexander Webb led the brigade at Gettysburg. Assigned to command the Philadelphians barely a week before Gettysburg, Webb distinguished himself during the battle and was wounded on July 3 at the height of Pickett's attack. General Webb received the Congressional Medal of Honor for his courage under fire, though he was not a favorite among the officers and men of his brigade who viewed the officer as a military appointment over a former commander who was discharged without just cause.

After Gettysburg, the Philadelphians fought through the Wilderness Campaign, Cold Harbor and to the outskirts of Petersburg. It was here that two of the brigade's regiments, their term of enlistment having expired, were mustered out of service and journeyed home to a hero's welcome. The remaining two regiments, including the 69th Pennsylvania Infantry, which had held a position along the stone wall on July 3, continued in service through the end of the war at Appomattox. In 1887, the veterans of that regiment planned to erect a monument at Gettysburg where they'd held the line that hot summer afternoon. Their interest sparked the idea for an association composed of veterans of the old brigade, and in 1887 the Philadelphia Brigade Association was formed. One of the first matters brought before the association was the intention of a group of southern veterans of Pickett's Division to also place a memorial at Gettysburg. The Philadelphians extended an invitation to the newly formed Pickett's Division Association to meet on the Gettysburg Battlefield, "in a spirit of 'Fraternity, Charity, and Loyalty.'" The southerners accepted the invitation to meet with their former foe at Gettysburg, but heated debates thwarted the efforts of those in favor of the summer meeting and a disappointing meeting with the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association sealed their decision not to go.

Upon hearing of their decision, John W. Frazier, secretary of the Philadelphia Brigade Association, authored a letter to the Pickett's Association urging them not to reject the invitation to the reunion. Frazier went so far as to offer help for the southern veterans to get their monument placed at Gettysburg where they felt it should go. After some debate, the invitation was re-accepted and a number of southerners made plans to visit Gettysburg as guests of the Philadelphia Brigade Association.

A train bearing 500 veterans of the Philadelphia Brigade including wives and children, left Philadelphia on July 2 and arrived at the Gettysburg Train Station later that day. A second train arrived two and one half hours later, bearing the Southern guests who were surprised and pleased by the greeting they received. Lining the street were the Philadelphians, resplendent in white pith sun helmets, who welcomed the Confederate veterans with cheers as a band struck up the tune "Dixie". Formed into ranks, the two groups marched side by side up Carlisle Street and into the center of town where they stood face to face and shook hands. A Northern writer observed: "Pickett's Division, for the first time, was in undisputed possession of Gettysburg." The old Confederates were treated with high honors by an excited group of Union veterans eager to show their admiration and respect. Though the day was beastly hot, the veterans stood in the square to listen to orations and speeches on behalf of both North and South. Among the honored guests was General Pickett's widow, LaSalle Corbell Pickett and her son.

Good feelings were everywhere and extended over into the next day when the former soldiers marched out of Gettysburg and to the Angle where the veterans of the 69th Pennsylvania dedicated their monument. There were more speeches to follow and the presentation of a flower arrangement and sentiment to Mrs. Pickett. The dedications and speeches lasted for several hours while the crowd broiled under a hot sun. The afternoon festivities ended with adjournment for refreshments being served under the shade of the Copse of Trees. Included were chilled kegs of beer which, no doubt, added to the merriment of the participants in blue and gray that afternoon. Some of the veterans camped in tents erected near the High Water Mark and pandemonium broke out at midnight when an impromptu fireworks display began in early celebration of the 4th of July.

The following day, the southerners paraded across the fields, the scene of their great charge 24 years gone, and up to the gray stone wall. Behind the wall stood the helmeted Philadelphia Brigade Association veterans with extended hands. The two sides met and shook hands, not as former foes, but as Americans. Reconciliation had come at last to these men who had sacrificed so much on these bloody fields.

- Carol Reardon, Pickett's Charge in History and Memory, University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 1997

- George R. Stewart, Pickett's Charge- A Microhistory of the Final Attack at Gettysburg, July 3, 1863, Press of Morningside Bookshop, Dayton, 1980

- Kathleen Georg and John Busey, Nothing But Glory, Pickett's Division at Gettysburg, Longstreet House, Hightstown, NJ, 1987

- Earl J. Hess, Pickett's Charge- The Last Attack at Gettysburg, University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 2001

- LaSalle C. Pickett, Pickett and His Men, J.B. Lippincott Company, Philadephia & London, 1913