Colonel Charles Shiels Wainwright enlisted in the First New York Artillery in 1861. Though having had some experience in the New York State militia, the army was a novel experience. Wainwright enthusiastically threw himself into his role as major of the regiment. That fall he purchased a journal to record his experiences during the war, both in camp and on the battlefield. They remain as one of the finest accounts of life as a Civil War soldier and of the war experienced from the saddle. The first day of the battle was marked by a lack of coordination by Union commanders. The mobile Wainwright was in several areas during the fighting and left a blunt and almost amusing account of the difficulty the Union commanders faced in the fields west of Gettysburg. This is his story from A Diary of Battle, The Personal Journals of Colonel Charles S. Wainwright, 1861-1865, edited by Allan Nevins.

"July 1, 1863, Wednesday: We breakfasted soon after sunrise, but it rather promised then to be a quiet day for us. I was just finishing up my monthly return when the order came to move at once. The order was from (General Abner) Doubleday, and placed the Third Division on the lead, and the First at the rear. So soon as my command had hauled out, as they had to wait for the Third Division in rear of which they were to march, I rode on ahead to learn what I could as to the prospects of a fight. I saw General Reynolds, who said that he did not expect any; that we were only moving up so as to be within supporting distance to (General John) Buford, who was to push out farther. At the corners where Reynolds had his headquarters the Third Division was turned off by him on a road to the left. General Reynolds then rode on, and took the First Division ahead with Hall's (2nd Maine) battery, which being camped near three miles in advance had an hour's start ahead of us. We moved along very quietly without dreaming of a fight, and fully expecting to be comfortably in camp by noon. So confident of this was I that, for the first time, I threw my saddlebags into the wagon, and was thus left without my supply of chocolate and tobacco, without brush, comb, or clean handkerchief. My horse 'Billy' cast two shoes on the road. I had no hesitation on stopping at a farmhouse with one of my forges until they could be replaced and even sat there ten for fifteen minutes longer until a heavy shower was over. I then rode up to the head of my brigade, where I found General Doubleday.

"This was about two miles before coming to Gettysburg and between ten-thirty and eleven o'clock. We were just speaking of General Meade's promotion and Doubleday was just saying that Sykes was his junior, and they ought to give him a corps, when my attention was called to the smoke of shells bursting in the air. On listening we could hear the sound of cannon apparently some three or four miles off, which we supposed to be from Buford's cavalry. In a few minutes, however, an officer... came up with orders for us to push on as fast as possible, as Reynolds was engaged over beyond the seminary.

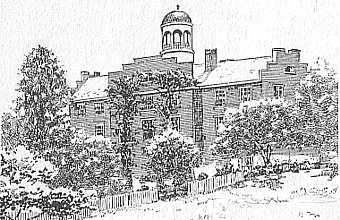

|

| The Lutheran Seminary (Battles & Leaders) |

"Passing then to the right of the railroad cut, on to the wooded knoll, I found that it had just been occupied by Robinson's division and Cutler's brigade. The lay of the ground was very intricate, so that it took me some time to make out the disposition of our troops; which proved to be all sorts of ways. As I was coming out I saw a line of rebels advancing towards Cutler's flank, and rode back to tell him, as I had no one with me... As I came out again I saw a portion of the Eleventh Corps moving forward in line facing north, so that the two corps formed a right angle at the knoll where Robinson was. They had two batteries with them which were just opening fire. Having thus made myself well acquainted with the ground and as far as possible with the dispositions of the troops, I rode to report to Gen'l Doubleday.

"Somewhere around three o'clock... a long column of rebels came out of the wood a mile or so in our front and filed off to our left. This was soon joined by another column, which when they faced into line formed a second line for them. They marched along quietly and with confidence, but swiftly. I watched them from the battery and am confident that when they advanced they outflanked us at least half a mile on our left. So soon as they were within range I opened on them with the four guns (Battery L, 1st New York), but a brigade of the Third Division sent to support the battery persisted in getting in front- that being the commander's idea of supporting. The rebel lines advanced rapidly. There was not the shadow of a chance of our holding this ridge even had our Third Division commanders had any idea of what to do with their men... I therefore soon ordered Lieutenant Bower to take his four guns back to the Seminary Ridge, to the position he had previously occupied about a hundred yards south of the college.

|

| Doubleday |

"When I returned (to the seminary), I found the Fifth Maine limbering up. I stopped them, when Lieutenant Whitaker told me that General Wadsworth had said they had better withdraw. Remembering what I had supposed to be Howard's order to hold Seminary Hill to the last, I had no notion of going off, and rode around to see that none of the guns moved. An officer now informed me that a rebel line was advancing on our right. Looking at it, I was sure that it was the Eleventh Corps, and could not be convinced to the contrary until they opened fire on a portion of that corps which I could now see making for the town. I then at once ordered all to limber up and move at a walk towards the town. I would not allow them to trot for fear of creating a panic. But I had very little hope for getting them all off, for the rebs were close upon us; so near that a big fellow had planted the colors of his regiment on a pile of rails within fifty yards of the muzzles of Cooper's gun at the moment he received his order to limber up. As I sat on the hill watching my pieces file past and cautioning each one not to trot, there was not a doubt in my mind but that I should go to Richmond. Each minute I expected to hear the order to surrender for our infantry had all gone from around me, and there was nothing to stop the advancing line. Just as the last of Stewart's caissons was coming into the road, a number of the enemy's skirmishers, sweeping around the south side of the college buildings, opened fire across the road at about fifty yards distance. Our infantry did not return the fire, so there seemed no chance but what they would kill all my horses. Perhaps, though, it was well for me that our infantry instead of making fight took at once and in a body to the left, over the railroad... embankment. This cleared the road and I shouted, 'Trot! Gallop!' as loud as I could. It did not take long for the whole eighteen pieces and six caissons to be in full gallop down the road, which being wide allowed them to go three abreast. As I saw the head carriages already at the turn of the road just before entering the town, I felt that now all were safe. And my next duty being to look out a new position for them I galloped to the front. In order to get by the batteries I was obliged to climb over the railroad and enter the town by another street.

|

| The scene of Wainwright's retreat. This view is toward Seminary Ridge from Gettysburg. The Lutheran Seminary, which Wainwright refers to as the "college", is on the ridge at left. Wainwright's batteries raced down this road toward town as Confederates closed in from both sides. |

"The streets of the town were full of the troops of two corps. There was very little order amongst them save the Eleventh took one side of the street and we the other; brigades and divisions were pretty well mixed up. Still the men were not panic stricken; most of them were talking and joking. As I pushed through... to the top of Cemetery hill, the existence of which I now learned for the very first time. I reached the top of the hill almost as soon as my first battery. Here I found General Howard who expressed pleasure at seeing me and desired me to take charge of all the artillery, and make the best disposition I could of it..."

Colonel Wainwright played a key role in placement of his exhausted batteries around Cemetery Hill and experienced several narrow escapes from harm over the next two days of bitter fighting at Gettysburg. The following spring, he commanded artillery in the Wilderness Campaign and was active during the siege of Petersburg, the subsequent campaign to Appomattox Court House, and the Grand Review in Washington. After the war, Wainwright's activities are not as well documented. He remained in military service for a while, attaining the rank of general. He lived in New York, Europe, and finally settled in Washington, DC where he was incapacitated with blindness and after effects of malaria. He finally applied for a pension in 1902. Charles Wainwright died in 1907 and was buried in New York.