CHAPTER X.

The Christmas Packet—The Distribution of Gifts—A Visit by Dog Train, at Fifty-five Below Zero—Souwanas Tells How the Indians first Learned to Make Maple Sugar.

How great the excitement was which attended the arrival of the Christmas packet can hardly be realized by persons who have never been exposed to the privations of a land which the mail reaches every six months, and where they wait half a year for the daily paper. After this long waiting it is no wonder that a great shout was raised when far away in the distance the long-expected, heavily-loaded dog-trains were seen that for several hundred miles had carried the precious messages of love and the tokens of good will from dear ones far away.

This year an extra train well loaded with much-needed supplies for the mission was among the arrivals. Its coming was hailed with special delight by the children; for even in that Northland Santa Claus was not unexpected, and it was surmised by some of the wee ones that possibly some of his gifts would arrive about that time.

And they were not disappointed, for loved ones far away in more favored lands had remembered these little ones in their Northern home, where the Frost King reigns, and many and varied were the gifts which they now received.

"I am going to take Souwanas some of my candies," said Sagastao.

"And I am going to give him a nice red silk handkerchief," said Minnehaha.

The children had by this time pretty well learned his weakness for these things, and it was a pleasure now for them to think that they had it in their power to make him happy.

The next morning was, as usual, bright and cloudless, but it was bitterly cold. The mercury was frozen in one thermometer, and in the other one the spirit indicated fifty-five below zero. Yet so impatient were these spirited children to be off with their gifts to Souwanas, and with something also for each member of the family, that their pleadings prevailed. A cariole with plenty of fur robes was soon at the door, and with old Kennedy as their driver they were soon speeding away behind a train of dogs.

Indians are naturally alert and watchful, and so the merry jingle of the silvery bells was heard while the cariole was still at some distance on the trail. Cordially were they welcomed, and strong arms speedily carried them into the cosy wigwam where, in the center, burned a great fire of dry spruce and birch wood.

As the cold was so intense, and the children had permission to remain for two hours, it was decided that Kennedy should return home at once with the dogs, as it would have been cruel to have kept them out in the cold so long.

The heavy wraps were soon removed and the children were comfortably seated on the fur rugs provided for them. Then they very proudly opened their parcels and distributed the contents—their own gifts as well as those which had been sent to Souwanas and his family from the mission. Minnehaha reserved her special gift for the last. When all of her others had been bestowed she unfolded the beautiful red silk handkerchief and, going over to Souwanas, she did her best to tie it nicely around his neck.

The old man, genuine Indian that he was, was much moved by her winsome ways and handsome gift.

He said but little, but there was a soft, kindly look in his eyes that showed his gratitude more than any words could have done. It meant a good deal more than perhaps he would like to admit and those who saw it were thankful that they had observed it, knowing that it meant so much. Sagastao, who had already given him several presents, had held on to his box of candies. He had learned that for such things the old man could be coaxed to do almost anything, and now he held them out, and said:

"Now, Souwanas, as all the presents have been passed around, I have got some fine sweeties for you, but we must have a first-class Nanahboozhoo story for them."

"O yes!" said Minnehaha. "And as it is to be for sweeties let us have a nice sweet story of Nanahboozhoo this time."

"A sweet story you want? Well, before I begin let us fix up the fire and all get comfortably seated around it."

Then, as they usually did, the two white children cuddled as close to the inimitable story-teller as they could. Little cared they for the cold without or even for the occasional puffs of smoke which seemed at times to prefer to enter the eyes of the listeners rather than to go out at the orifice at the top of the wigwam.

"A sweet story," musingly said the old man, "in this land of fish, and bears, and wolves, and wildcats, and wolverines!" Then he paused long enough to fill his mouth again with the candies which he enjoyed so much.

"A sweet story. Then it must be of a land, south of this, where for some years I dwelt, many, many moons ago. A land where the Se-se-pask-wut-a-tik (sugar maple tree) grows and flourishes in all its beauty.

"There, in those wigwams, long ago lived the people whom we call the Hurons, the Dakotahs and the Ojibways. These Ojibways are cousins of my own people, the Saulteaux. Well, the story I want to tell you had its beginning long, long ago. One day there came a great embassage of Indians from the far South with words of peace and good will. They said that in their country they had no cold weather, and very seldom saw any snow. They said that the trees were different, and that many things grew there that they did not see in our Northern country. They brought with them many presents and were kindly received by our people, and then, after some weeks of feasting and speech-making, they returned home laden with the best gifts our tribes could bestow.

"Among the presents which these Southern Indians brought was a large quantity of sugar. This was the first time it was ever seen among the Indians of the North. It was very much prized, and was very carefully divided among the people so that each one had a small quantity. It did not last very long, for everybody was fond of it. When it was all gone the people were sorry, and the question was asked, 'Why cannot we send a company of our own people and get more of it?'

"This suggestion met with the favor of the tribes, and a large party of the best runners was selected, and being well supplied with rich presents and pipes of peace they started off to find the Southland and to obtain abundance of the sugar. Some weeks passed by before word was heard from them, and the news was very bad. Fierce wars had broken out among the tribes that lived between ours and those who dwelt in that far South. Our Indians had to fight for their lives. Many of them were killed, others were badly wounded, and of the large company that started out not more than half ever returned to their homes. The expedition was a complete failure.

"Still there was the memory of the sugar among them, and it happened that one day in the council somebody said:

"'Why not send to Nanahboozhoo?'

"Good!" shouted Minnehaha; "that is just what I thought they would do."

"Well, hold on," said her more matter-of-fact brother; "just as like as not Nanahboozhoo would give them salt instead of sugar, if he were in one of his tantrums."

Souwanas was not displeased at this interruption on the part of the children, and gladly availed himself of the opportunity thus offered to once more help himself to the sweets.

Earnestly appealing to Souwanas, Minnehaha, who always looked on the bright side of things, and who had a quick intuition quite beyond her years, said:

"It could not be a sweet story if Nanahboozhoo gave them salt instead of sugar; could it, Souwanas?"

The old man, as soon as his mouth was sufficiently emptied to resume his story, amused by the earnestness with which the child appealed to him, replied with the words, "Tapwa, tapwa!" (Verily, verily!)

Sagastao, however, unwilling to give in, retorted, "O 'tapwa, tapwa' doesn't mean anything, anyway."

Souwanas only laughed at this criticism, and proceeded with his story.

"So it was decided to send a deputation to Nanahboozhoo to tell him of the wish of the tribes to have Se-se-pask-wut (sugar), as had the tribes of the Southland.

"The deputation who started off to find Nanahboozhoo had a great deal of difficulty in finding him. It seems that a great strife had arisen between Nanahboozhoo and some of the underground Muche Munedoos—bad spirits, sometimes called the Ana-mak-quin—who had determined to kill Nokomis, the grandmother of Nanahboozhoo, because of their spiteful hatred of Nanahboozhoo, whom they knew they could not kill because he had supernatural powers.

"Nanahboozhoo had, as usual, been playing some of his pranks on them, and that was why they were determined to kill Nokomis."

"What were some of the tricks that Nanahboozhoo had been up to this time?" asked Sagastao.

"It would take me too long to tell you now," replied Souwanas.

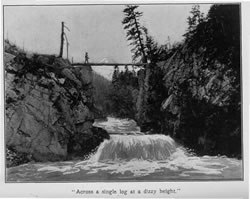

"Nanahboozhoo dearly loved his grandmother, although he was often giving her great frights, just as other grandsons sometimes do. So when he heard of what the Muche Munedoos were threatening he took up his grandmother on his strong back and carried her far away and made for her a tent of maples in a great forest among the mountains. The only access to it was across a single log at a dizzy height over a wild rushing river.

"It was now in the fall of the year, and the leaves of these trees were all crimson and yellow, so brilliant that when seen from a long distance they looked like a great fire. Thus it happened that when the bad spirits following after Nanahboozhoo and Nokomis saw the brilliant colors through the haze of that Indian Summer day they thought the whole country was on fire, and they turned back and troubled them no more. Nanahboozhoo was pleased that the beautiful maple trees had been of so much assistance to him. He decided to dwell among them for some time, so he prepared a very comfortable wigwam for himself and his grandmother.

"It was in the wigwam among the maples that the deputation found Nanahboozhoo. He received them kindly, and listened to their story and their request.

"At first Nanahboozhoo was perplexed. He was such a great traveler that he had often been down in the great Southland, and well knew how the sugar was there made. He had seen the fields of sugar cane, and knew the whole process by which the juice was squeezed out and then boiled down into sugar. He also knew that it required a lot of hard work before the sugar was made.

"When Nokomis heard the request of the deputation to her grandson she was very much interested—for had not Nanahboozhoo several times, when returning from those trips to the South, brought back to her some of the sugar?—and she had liked it very much; and so now she added her pleadings to theirs that he would in some way grant them their request.

"Of course Nanahboozhoo could not refuse now, so he told them that, as the beautiful maple trees had been so good to him and Nokomis, from this time forward they should, like the sugar cane of the South, yield the sweet sap that when boiled down would make the sugar they liked so much.

"He told them, however, that it was not for the lazy ones to have, but only for those who were industrious and would carry out his commands. Then Nanahboozhoo described to them the whole process of sugar making. He told them that only in the spring of the year would the sweet sap flow. Then they were to have ready their tapping gouges, their spiles and buckets. Great fireplaces were to be built and here, as fast as the sap was gathered from the trees, it was to be boiled down in their little kettles into the nice molasses; and then a little more, so that when it cooled it would harden into sugar.

"'Now,' added Nanahboozhoo, 'go back to your people and tell them that it depends on their industry between now and the spring who shall have the most of the sugar you love so well.' Then he skillfully modeled out a stone tapping gouge of the shape required to make the incision in the tree from which the sap would flow. With his knife he made a sample spile of cedar, the thin end of which was to be driven into the hole made by the gouge and along which the sap would flow. Then he told them to make plenty of buckets of birch bark, and thus be ready when the time came to secure an abundant supply of sap. Thus the art of making maple sugar first came to be known. Nanahboozhoo gave it to the Indians long ago. Then when the palefaces came they followed the same process. That is the way Nanahboozhoo showed us how to get the maple sugar."

But here the sound of the barking of the dogs, and the sweet tones of the silvery bells on the collars of the dogs that had come for the children, told that the two hours had passed away.

"Thank you ever so much," said the grateful Minnehaha, as she rose to have loving hands carefully wrap her up for the return ride, "for that sweet, sweet story. It was so good of Nanahboozhoo to tell them about the sap in the maple trees, even if it is only there in the spring time."

"I think old Nokomis deserves a good deal of the credit," said Sagastao. "It seems to me that Nanahboozhoo would not have done it if she had not made him."

"Well, Nanahboozhoo did it, anyway, and so we and the Indians have our maple sugar and molasses, and I am glad. And so, hurrah for Nanahboozhoo!" Thus replied Minnehaha.

Here Souwanas lifted the well-wrapped-up child, and carried her out to the cariole, where she and her brother were speedily covered and tucked in among the warm robes.

"Marche! Marche!" was shouted to the dogs by the driver, and away they sped over the icy trail with such speed that it was not long ere they were again safe and happy in their own cozy home.