CHAPTER III.

More about Mary and the Children—Minnehaha Stung by the Bees—How the Bees Got Their Stings—What Happened to the Bears that Tried to Steal the Honey.

The next morning while Mary was dressing them the children told her of their adventures in the wigwam of the Indians. Mary was really interested, though she pretended to be disgusted at the whole thing, and professed, in her Indian way, to be quite shocked when they both confidentially informed her that they had had such a good time that they were going again even if they had to run away and be whipped for it.

This was terrible news for Mary, and placed her in an awkward position. To tell the parents of the children's resolve was something she would never do, as it might bring down upon them some of the punishment which was quite contrary to her principles. Yet, on the other hand, to let them go and to give no information might cause more trouble than she liked to think of.

Neither could she bear the thought of the two children returning from another day's outing with their neat clothing and pretty faces soiled and dirty. Do as they might, she had never once informed on them, and she had no mind to begin now. She earnestly pleaded with them not to carry out their resolve. The little ones were shrewd enough to see that they had thoroughly alarmed her, and they were in no hurry to surrender the power which they saw they had over her.

Mary never said a word in English. She understood a good deal that others said, but she never expressed herself in other than the Indian language. Hence both little Sagastao and Minnehaha always talked with her in her own tongue.

Minnehaha, seeing Mary's anxiety at their determination to run away to the Indians, thought of compromising the matter by insisting that Mary should tell them more tales. If she would do this they "would not run away very soon;" especially did she emphasize the "very soon." This was hardly satisfactory to Mary, but as it was the best promise she could get she was obliged to consent.

Little Sagastao, who was Mary's favorite, once more unsettled her when he said, "Now, Mary, remember, we have only promised not to run away very soon. That means that we intend to do it some time."

It seems that the little conspirators had talked it all over in the morning in their beds, and had decided how they would get stories out of Mary without really promising not to run away to the wigwam of Souwanas.

The children, being dressed, were taken down by Mary to prayers and breakfast, after which an hour was allowed in summer-time for outdoor amusement before the lessons began. Little Sagastao generally spent his hour, either with his father or some trusty Indian, playing with and watching the gambols of the great dogs, of which not a few were kept at that mission home. Minnehaha was with her mother, and was interested in the bestowal of gifts to the poor widows and children who generally came at that hour.

Owing to the isolated situation of the mission, and the fact that there were no organized schools within hundreds of miles, some hours of the forenoon were devoted to the education of the children in the home. The afternoons, according to the season, were devoted to reading and amusement.

Mary, the nurse, while able to read fluently in the Cree syllabics, had no knowledge of English. As the children's education progressed they wanted to teach Mary. She stubbornly resisted, however, declaring that if they taught her to read English they would want to make her talk it.

The mother noted the unusual expectancy manifested by the children during the day, and on inquiring the reason was promptly informed that Mary had promised to tell them a story, or legend, and "had got to do it."

"Why has she got to do it?" said the loving mother, struck with the emphasis which they had placed on the word.

The little mischiefs were cunning enough to see that they had nearly run themselves into trouble, and were wisely silent. Mary also noticed this, and at once her great loyalty to the little folk manifested itself, and quickly turning to her mistress she said, with an emphasis which was quite unusual:

"Mary has promised them a story, and as she always keeps her word she has got to tell it."

Saying this she quickly sprang from the floor, where she had been sitting, and taking a child by each hand she marched with them out of the room.

"Hurrah for you, Mary! you saved us that time," said little Sagastao.

Mary would not have been sorry if in some way the parents received an inkling of what was in the minds of the children, yet she had such peculiar ideas that she would never herself be the one to convey that information.

During the brief summer months the pleasantest walks were along the shores of the lake. Many were the cosy little cave-like retreats where Mary often led the children. There, with the sunlit waters before them, and the rippling waves making music at their feet, the old nurse crooned out many an Indian legend or exciting story about the red men of the past. To-day, however, she was perplexed by the attitude of the children and could not select any story that she thought of sufficient interest to divert their minds from Souwanas and Nanahboozhoo. So for a time they wandered on along the pleasant shore, or turned aside to gather the brilliant wild flowers.

A scream of pain from Minnehaha interrupted their pleasure. In gathering some wild lilies she was stung on both hands by some honey bees that were in the flowers. Mary quickly made a batter of clay and bound up the wounded hands in it. Then she sat down and took the child in her lap.

"Naughty bees to sting me like this," said Minnehaha, with tears streaming down her cheeks. "I was not doing them any harm."

"Yes, you were, and so were we all," said the brother. "We were carrying off the flowers from which they get their honey, which is their food."

"Well, they might let us have a few flowers without stinging us," replied Minnehaha.

The intense pain of the stings rapidly abated under Mary's homely but skillful treatment, and as the child still retained her place in Mary's lap she said,

"Can you tell us why such pretty little things as bees have such terrible stings? My hands felt as if they were on fire when I was first stung, and I could not help crying out with the pain."

"Well," said Mary, "there was a time when the bees had no stings, and they were as harmless as the house flies. They were just as industrious as they are now, but they had any amount of trouble in keeping their honey from being stolen from them, for every creature loves it.

"In vain they hid their combs away up in hollow trees and in the clefts of high rocks. The bears, which are very fond of honey, were ever on the lookout for it, and were very clever in getting it when once they found where it was hidden away. Birds with long beaks would suck it out, and even the little squirrels were always stealing it. The result was that whole swarms often starved in the long winters, because all their honey, which is their winter food, was stolen from them. The bees were in danger of being destroyed. They gave up working in great numbers together, and scattered into little companies, and in the most secret places tried to store away a little honey, just enough to keep them alive from season to season. But even these little hives were often discovered and the honey devoured.

"Things had come to such a pass with them that they had almost given up hope of lasting much longer.

"Fortunately for them, word was circulated that Wakonda, the strong spirit—the one who sent the mosquitoes—was coming around on a tour, to see how everything was progressing. He was greater than even Nanahboozhoo, and was perhaps a relative of his, but he very seldom appeared, or did anything for anyone. However, it happened that he had this year left his beautiful home at Spirit Lake and was journeying through the country, and he was willing to help all who were in real distress.

"So the bees resolved to apply to him for help. Wakonda received them very graciously, and ate heartily of the present of beautiful honey which some of them had made and had succeeded in keeping out of the way of bears and their other enemies.

"When his feast of honey was over he listened to their tales of sorrow and woe. He was indignant when he heard of the numbers of their enemies, and of the persistency of their attacks upon such industrious little creatures.

"For a time Wakonda was uncertain as to the best method to adopt to help them. He dismissed them for that day, and told them to come again on a day he mentioned, saying that by that time he would know just what to do—for help them he would. The bees were so delighted with this news that they could not keep it to themselves but must go and tell their cousins, the wasps and hornets, and even bumblebees.

"When the appointed time arrived the bees were on hand—and so were the wasps, hornets, and bumblebees. Wakonda welcomed the bees most kindly, but was a little suspicious about their visitors, and he asked some sharp questions. But the bees were in such good humor about the help that was coming that they did not refer to the bad habits of their cousins at all. Then Wakonda made a speech to the bees, and told them how much he loved them for their industrious habits, which he wished all creatures had. He praised them for the fact that, instead of idly wasting the summer days, they used them in gathering up food for the long, cold winter.

"Then he proceeded to give them the terrible stings which they have had ever since, and as the wasps and hornets claimed to be their cousins Wakonda was good-natured enough to give them the same sort of weapons. Some people, especially boys, think this was a, great mistake, and would be very glad if Wakonda had refused to give stings to the yellow wasp and the black hornet."

"Well, what happened after the bees got their stings?" said Sagastao.

"A good deal happened," said Mary, "and that very soon. A lot of them, without as much effort to conceal their nest as formerly, selected a tall, hollow tree, and using a big knot hole as the door began secreting their honey in it. They had made the combs, and were now filling them, when along came a couple of bears. These animals, as you have been told, are great honey thieves, but they always had hard work to find where the timid bees had cunningly hid it away, and now they could hardly believe that right here before them was a great swarm of bees filling the air with their buzzing as they flew in and out of the knot hole.

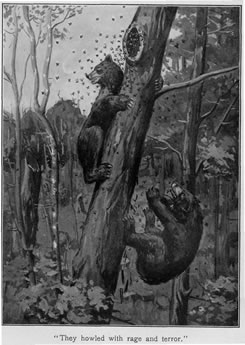

"With saucy assurance they at once began climbing the tree, expecting to be able to put their long paws into that big hole and draw out the combs. But they never reached that knot hole. The noise they made in their climbing alarmed the bees. Out they came in great numbers, and now, instead of flying around in a panic, like so many house flies, and seeing their honey devoured, they at once flew at their enemies, the bears. They stung them on their noses and about their eyes and lips, and indeed in every spot where they could possibly reach them with their terrible new weapons.

"The bears could not make out what the trouble was. They howled with rage and terror, yet they were resolved to get that honey, and still tried to crawl up higher on the tree. But at length the bees mustered in such vast numbers—for those away gathering honey, as they returned, joined in the attack—that the bears became wild with pain and fear, and had to give up their effort and drop to the ground. Even then the bees gave them no peace, and continued to sting them until they were obliged to run into the dark forest for relief.

"Thus it happens now that almost all creatures that bother the bees are similarly treated."

"Well," said Minnehaha, "they need not have stung me because I was picking a few flowers; but, after all, I am glad they have their stings or I suppose we should never have any honey."

"They are not big enough to have much sense," replied Sagastao, "and so they go for everyone that gets in their way."

Mary now carefully removed the clay poultices, which had effectually done their work. A wash followed, in the waters of the lake which rippled at their feet, and soon not the slightest trace of the sting remained. By the time they reached home both pain and tears were well-nigh forgotten.

That evening before the children were sent to bed they overheard Jakoos, who had come to the house with venison to sell, telling in the kitchen a story that he had heard from Souwanas about a naughty fellow, called Maheigan, who tried to capture a beautiful kind-hearted maiden, Waubenoo, and of how Nanahboozhoo thrashed him, and then afterward, because of some naughty children not holding their tongues, Waubenoo was turned into the Whisky Jack.

What the little children overheard had very much excited their curiosity, and so when Mary was putting them to bed they demanded from her the full story.

As this was one of the Saulteaux Indian legends, while Mary was a Cree, she was not familiar with it. She told the children that she knew nothing about it, but this by no means set their curiosity at rest.