CHAPTER IX.

Kinnesasis—How the Coyote Obtained the Fire from the Interior of the Earth.

A great time the children had in the wigwam of Kinnesasis. He was such a jolly little old Indian, and he was specially happy to-day when the children opened out the gifts and presented them. He was more than delighted with a suit of black clothes sent him from a distance by friends who had heard about him and his needs. He quickly put on the whole suit, which fitted him very nicely, and then much amused the children by saying:

"I am sure the man who made these clothes is in heaven, or, if not yet dead, he will go to heaven when he dies."

"Why, Kinnesasis, it is the kind friends who sent you these clothes you ought to thank, and not make such a fuss over the man who made them; he was paid for making them," said Sagastao. But Kinnesasis could only think of the man who made the suit of which he was so proud.

Kinnesasis's old wife was, if possible, still more delighted with her presents than the old man with his. She and Minnehaha were always the best of friends, and now as the child handed her gift after gift of warm clothing and food her joy knew no bounds, and, old as she was, when some warm shoes were given her, she sprang up and began singing an Indian song, while with all the agility of a young maiden she spun around the wigwam in rhythmic measure to her words, which, roughly translated, are as follows:

"The Good Spirit has pity on me,

Though for days I had little to eat,

I was wretched and sad in my heart,

I was cold, O so cold! in my feet.

"But now I have plenty of meat,

Clothes for my body, shoes for my feet,

I'll not grumble, nor sorrow, but praise

The Good Spirit the rest of my days."

"Well done!" shouted the children when the old woman stopped. They were greatly delighted with her performance. Kinnesasis, however, who, as well as his wife, was now a church member, professed to be much shocked at seeing her thus dancing, as though in the wild excitement of the Ghost Dance. But both Sagastao and Minnehaha stood up for the old wife. They said the words she sang were good enough for the church, any day, and they were sure nobody could find fault with her thus showing how glad and thankful she was.

And nobody ever did find fault and soon was the affair almost forgotten, for now the merry jingling of more dog bells was heard, and who should come into the wigwam of Kinnesasis but the parents of Sagastao and Minnehaha!

Cordially were they greeted. At first it was difficult for them to recognize the staid little gentleman in his full suit of broadcloth as the lively but generally ill-clothed Kinnesasis. The visitors—who quickly saw and were delighted with the transformation—greeted him as though he were some distinguished stranger. This vastly amused the children. Screaming with laughter at Kinnesasis's pretense of keeping up the farce, they shouted out, "Why, this is only our dear old Kinnesasis. He is no great stranger. It is only Kinnesasis with his new clothes."

"Well," then was asked, "who is that charming old lady over there with such a fine shawl and brilliant handkerchief on, and such fancy new shoes on her feet? Surely she is a stranger."

"No! No!" the children again shouted. "Why, that is Kinnesasis's wife, with her new presents on! My! doesn't she look nice!"

Here the little ones seized hold of the happy old Indian woman and made her get up and show herself off in her new apparel, of which she was just as proud as Kinnesasis.

"And she gave us such a jolly dance in them, papa! Wouldn't you like to see her do it again?" cried Minnehaha.

But here Kinnesasis, pretending to be shocked beyond measure, in a most diplomatic manner directed the attention of the parents to some other matter, and so the mischievous child did not succeed in making a church scandal by inducing one of the flock to dance before the missionary.

"Tell us, Kinnesasis," said Sagastao, "how it was that that old man and his daughters first obtained the fire which Nanahboozhoo so cleverly stole from them and gave to the Indians long ago."

At first Kinnesasis hesitated about telling the old legend, saying that he did not think the father and mother of the children would care for such stories.

"Don't they, though!" cried the children. "You don't know them very well, then, if you don't know that they like stories just about as well as we do."

And with this they at once appealed to the parents, who of course sided with them and expressed their desire to listen to this story that the children had told them they were to hear from dear old Kinnesasis.

Throwing some more logs on the fire, around which the white visitors with the Indians gathered, Kinnesasis began:

"It was long ago, when I was a young lad, that I heard the story from the old story-tellers of our people. I had traveled with my father for many days far toward the setting sun. We reached the land of the great mountains, and there, with our people of those regions, we spent some moons. It was while we were among them that I heard from the ancient story-teller the legend of how the fire was stolen from the center of the earth, where it was kept hidden away from the human family.

"That there was such a thing as fire was well known. It had been seen bursting out of the tops of distant mountains, and there had been times in great thunderstorms, when the lightning had set fire to dead trees—and indeed in this latter way the Indians had become acquainted with its value to the human race. But they had not taken care to keep it burning, and no one had been appointed to specially look after it.

"The reason why fire had not been from the first given to men was because when the race was created the fire was not much needed. The earth was then much warmer than it is now. There was no snow or ice ever seen except on the tops of the very highest mountains. Great animals now all dead, and others that could only live in the hottest countries, lived all over these great lands. Then there was abundance of fruit and nuts and roots that were all very good for food. Then some great disaster happened to the world and soon it began to grow colder and many animals, and even families, perished. Snow and ice appeared where they were never seen before. There was great suffering from the cold. The hunters began to kill the animals for food. They were now not satisfied with the fruit and roots, they wanted something better.

"So the fire was much needed. But where it was, or how to get it, was the question. Fortunately an old dreamer dreamed a dream about it. As the council assembled to hear his dream he told them that the fire was preserved in the heart of the earth by a magician called Sistinakoo, and that it was kept very carefully surrounded by four walls, one within the other, in each of which was a single door. At the first door a great snake kept guard. At the second door a mountain lion or panther was the guardian. A grizzly bear guarded the third door, and at the fourth and last door Sistinakoo himself kept watchful care over the precious fire that smoldered on a stone altar just inside this last wall.

"When the council heard all this they were almost discouraged. They thought it would be impossible for anyone to get by all of these guards and steal the fire.

"They first asked the fox to try, but he only reached the first door when the great snake nearly made a meal of him. Thoroughly frightened, he rushed back to the top of the earth and told of his narrow escape.

"For a time nothing more was done to try and get the fire. The people continued to suffer, for the earth kept getting colder and colder and ice and snow were now to be found in lands that had previously been comfortably warm. So the council was called again, and the question again raised as to what could be done.

"It happened that there came to the council a very old man who remembered a tradition, handed down from his forefathers, which said that part of the earth beneath us was hollow, and that some of the animals, even the great buffaloes, had dwelt in those underground regions before they came to dwell on the surface of the earth. He said that the coyote, the prairie wolf, was the last one to leave, and that he was sure that he still remembered the route to the very spot where Sistinakoo, the head chief of the regions, guarded the fire so jealously."

"Why should they so guard the fire, and be so careful about letting people have it, when we know how good it is?" asked Minnehaha.

"Because," replied Kinnesasis, "there was a tradition that at some time or other the fire should get the mastery over men, and the whole world be burned by it, and they thought that they would carefully guard it from getting scattered about by careless people who might set the world on fire."

"Well, go on, Kinnesasis, and tell us the rest of the story," said the impatient Sagastao.

"So when the Indian council heard this story they sent for the king of the coyotes and told him of their wish that he should return to that underworld and bring up the fire for their use.

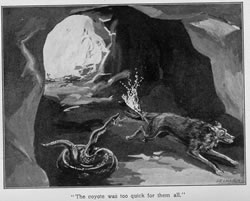

"To their surprise and great delight the coyote said he would go, and he immediately began his preparations for the journey. So greatly had the cold increased that he found the dark mouth of the entrance under the mountains almost surrounded by snow and ice. After traveling for some time in the darkness he reached the outer wall, where he waited, a little distance from the door, until the snake was taking his usual sleep. Then he quickly stepped past him. Knowing the habits of the other animals, he waited until they were asleep and then he noiselessly passed them all. Even Sistinakoo himself was sound asleep. So the coyote crept silently up to the fire and lighted the large brand or torch that was securely fastened to his tail. The instant it began to blaze up, as the coyote rushed out through the first door, Sistinakoo shouted, 'Who is there? Some one has been here and has stolen the fire!'

"He at once began to make a great row and loudly called to the different keepers to close the doors in the walls. But the coyote was too quick for them all, and ere the sleepers were wide enough awake to do anything he had passed through all the doors and was far on his way to the top of the ground. The fire was gladly received by the people, but after some time, when some big prairies and forests had been burned up by it, the men got fearful that the world might be destroyed and so they intrusted it to the care of the old magician and his two daughters, with orders to be very careful to whom they gave any. It was from them Nanahboozhoo stole it, to scatter it once more freely among the people as we now have it.

"But the tradition was still believed in the days of my grandfather that, good as the fire was to warm us, and cook our food, it would yet become our master, and do the world much harm."

Kinnesasis was thanked by all for his recital of this suggestive legend, especially by his older listeners, who saw much in it that was in harmony with the earlier beliefs of other nationalities.

By this time, however, the dogs in their trains were impatiently barking, and longing to get back home for their suppers. So, after farewell greetings to Kinnesasis and his wife, one cariole after another was loaded, and away the happy ones sped over the icy expanse of the frozen lake.