CHAPTER XI.

Mary Relates the Legend of the Origin of Disease—The Queer Councils Held by the Animals Against Their Common Enemy, Man.

"Mary, how is it that I get sick sometimes," said Sagastao the following summer, "and have to take medicine that I dislike? Why can't we always be well?"

For the last week or ten days Mary had been most devoted and faithful in watchful care over her restless charge, who had been very sick but was now rapidly recovering.

"As soon as you are a little stronger I will tell you the legends of sickness and medicine, as handed down by our Indian forefathers," said Mary, "but now you must only rest, and eat, and sleep."

"Well, Sakehow" (beloved), his pet name for his faithful nurse, "I will try and mind you; don't forget."

The next week was one of rapid recovery, and very proud, indeed, was Mary when she led forth the two children, in the bright sunshine of a delightful summer day, to a cozy resting place among the rocks where the waves of Lake Winnipeg rippled on the sandy beach at their feet.

Minnehaha was eager for a story about the sweet birdies or the brilliant flowers, but the young invalid had his way this time, and Mary proceeded to tell the story of the Indians' idea as to the origin of sickness and disease.

"Long, long ago," said Mary, "all the animals and birds on this earth lived in peace and harmony with the human family. Then there was food for all in abundance without any shedding of blood. Even the wild animals, that now live by killing and devouring each other, found plenty of food in the fruits and vegetables that then were so abundant.

"Men and women also lived on similar things, and were contented and happy. But as the years went on the people became so numerous, and their settlements spread over so much of the earth, that many of the poor animals began to be cramped for room.

"Even this could have been borne, but by and by men began to make bows and arrows, spears and knives, and other weapons, and began to use them on the defenseless animals. Then soon they began to eat the flesh of the animals, and presently they found that they preferred the meat thus obtained to the fruits and vegetables of the earth.

"Formerly they had made their garments out of the fiber of the trees and plants, which the women carefully prepared and wove; but after a while they discovered that the skins of the buffalo and deer and other animals, when well prepared, made better and more durable garments and wigwams than the materials they had previously used. As time went on the destruction of the larger animals increased, and men became so much more cruel than formerly that even the frogs and worms, that in the earlier days were never harmed, were now destroyed without mercy, or by sheer carelessness or contempt. Thus the animals came to be in such a sad plight that it was resolved by them to call great councils of their members together to consult upon what could be done for their common safety.

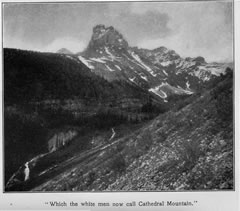

"The bears were the first to assemble. They gathered together on the peak of a great smoky mountain, which the white men now call Cathedral mountain, and the great white bear from the Northland was appointed chairman."

"Well, that was funny," said Minnehaha. "Just fancy a big white bear sitting up in a chair! Why, he would need a whole sofa to hold him."

"Don't be silly, child," said the patronizing brother. "It was a bears' council and, of course, the chairs used were bears' and not men's."

When Mary was appealed to to settle the question she could only say, "As the council was held on the top of a mountain perhaps the bears sat on the rocks. But never mind; let me go on with the story.

"After the white bear had made his speech he took his seat and said he was now ready to hear the statements of the different bears who had assembled to lodge their complaints against the way in which men killed their relatives, devoured their flesh for food, and made garments and robes out of their skins.

"Nearly every kind of bear had grievous statements to make, and so blood-curdling were some of their recitals that it was decided to begin war at once against the human race.

"Then the question was asked, 'What weapons shall we use against them?' After some discussion it was decided to use bows and arrows, the favorite weapons of their enemies.

"'And what are they made of?' was the next question.

"This was soon answered by a bear who had been caught when young and kept captive for a couple of years in the wigwam of one of their enemies. He had often seen the process of making bows, and he was now able to tell all about it, and even to do the work himself. It was not long before the first bow, with some arrows, was manufactured, and there was great excitement when the first trial of it was made. A large strong bear was selected to shoot the first arrow. To their great disappointment the trial was not a success, for it was found that when the bear let the arrow fly, after drawing back the bow, his long claws caught in the string and spoiled the shot. Other bears tried, but they all had long claws, and they all failed. Then some one suggested that this difficulty could be overcome by their cutting off their long claws. But here the chairman, the white bear, interposed, saying that it was very necessary that they should have their long claws in order to climb trees, or up steep rocky places. 'It is better,' said he, 'for us to trust to our claws and teeth than to man's weapons, which certainly were not designed for us.'

"The bears remained in council until they got very hungry, but think as much as they might they could not devise any satisfactory plan, for they are stupid animals after all, and they dispersed to their different homes no better able to fight the human race than before.

"Then the deer next held a council. Representatives of all the different kinds of deer, from the great elk and moose down to the smallest species in existence, assembled in a beautiful forest glade. The moose was selected as chief. After a long discussion it was resolved that in revenge for man's tyranny they would inflict rheumatism, lumbago, and similar diseases upon every hunter who should kill one of their number unless he took great care to ask pardon for the offense. That is the reason why so many hunters say, just before they shoot, 'I beg your pardon, Mr. Deer, but shoot you I must, for I want your flesh for food.' They know that if they do this they are safe.

"The Cree legend is that it is the bear that has to be propitiated by gentlemanly expressions when he is being approached to be killed. I well remember being with a couple of hunters closely following up a bear, and just before they fired they kept saying, 'Excuse us for shooting you, Brother Bear, but we must do it. We want your warm fur robe, our families want your meat, our girls want your grease to put on their heads, so you must excuse us, Brother Bear. Please do, Brother Bear; please do.' Thus they went on at a great rate until he was killed.

"But many forget it, and the spirit of their chief knows it and is angry, and he strikes those hunters, or their relatives, down with rheumatism or some other painful disease.

"Next the fishes and snakes and other reptiles held their council, and they decided that as the human race had now become such enemies to them they would trouble them with 'fearful dreams' of snakes twining about them, and blowing their poisonous breath in their faces, by which they would lose their appetites and die, while others of them would seek opportunity to make the water they drank, or even the air they breathed, unwholesome. The poisonous ones were also directed to use every opportunity to kill with their deadly bites whenever possible.

"The birds also held a council, over which the crow was appointed chairman. The eagle objected, and wanted the place, but he was voted down because there were so few of his kind, and these were only hunted for their feathers to adorn the war bonnets of the great chiefs and warriors. The crow was appointed because he was always with the human race and knew the various schemes and tricks they were inventing to injure the birds and animals of various kinds. After much deliberation the birds decided to give colds, and coughs, and throat diseases, and consumption, to the human race, and to thus lessen their numbers that there might be room for all creatures.

"The insects and smaller animals then held their council, and the grubworm was appointed to preside over the gathering. He was so elated over his election, and that they had arranged a scheme which should be fatal especially to women, that he fell over backward and could not get on his feet again. So from that time the grubworm has only been able to wiggle in that way. There was any amount of talking and buzzing among the crowd. The frog was especially noisy and angry in his remarks.

"'It is high time,' said he, 'that we began to do something against this cruel human race, or we will soon be swept off the earth. See how my back is ugly with lumps and sores because men have so kicked and knocked me about!'

"Others followed in the same strain of indignant protest against man's cruelty. Even the flies and mosquitoes had something to complain of.

"Well, after the buzzing, and the croakings, and the hummings and angry talkings were over, they settled down to business.

"Some were appointed to poison the waters so that malarias and fevers should attack the now hated race. Others, such as the flies and mosquitoes, were to carry in their bites and stings many diseases. Thus it has come to pass that there is more damage done to the hated human beings by these bites and stings than the mere smarting pain caused at the time of the bite. Thus, because the human race changed from being all kindness to the rest of the creatures, both great and small, into being cruel and savage, all these various creatures have combined to bring dreadful diseases among men in revenge for their own wrongs."

"That is too bad," said Minnehaha. "Why could they not have kept on loving each other all the time, instead of things being as they are now?"

Sagastao, who had laughed at the idea of the mosquitoes coming to a council, and of their having anything to complain of, said, "I would like to know what mosquitoes lived on in those good old days you speak about. Now they are after me lively enough." And he slowly lifted up his hand, on the back of which a couple were rapidly filling themselves with his blood.

But Mary, who, Indian like, was wise and observant, only said, "Wait a minute or two and I will show you." Then she quickly hurried back into a swampy place and soon returned with a thick juicy leaf, to the under side of which several mosquitoes were still clinging, with their bodies distended with its juice.

"There," she said, as she carefully held the leaf sideways, "that is what most of the mosquitoes still live on. They attack our race in revenge for our being so cruel as to kill so many of the animals, large and small, but this, as you can easily see, is their natural food."

This appeal to the eye quite silenced the children, who had considered the whole story as only an Indian legend to be amused with.

Mary, who had often been worsted by the sharp criticisms and inquiries with which they were apt to receive her pet Indian legends, was quite delighted at her apparent triumph, so she hastily sprang up, saying:

"It is time we were going home. Some other day I will tell you the story of how the medicines came."