CHAPTER XII.

The Naming of the Baby—A Canoe Trip—The Legend of the Discovery of Medicine—How the Chipmunk Carried the Good News.

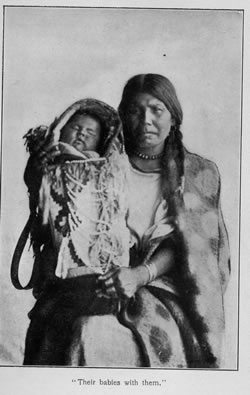

There was great excitement among a number of Indian men and women who had gathered on the shore in front of the mission one pleasant summer morning. Grave Indians, with Souwanas in their midst, were calmly discussing some object of interest, while Mary and a party of women, some of whom had their babies with them, were much more noisy, talking rapidly about something which was evidently a matter of exciting interest. Even Sagastao and Minnehaha were rushing in and out of the house and running from one group of Indians to the other, full of eager inquiries and pleasant anticipations. What could it all be about?

Let us ask the children, for such little people often know more than we are likely to give them credit for. Here comes Minnehaha, and we ask her the cause of such an early gathering of the Indians, and the reason why they are so unusually interested in some matter unknown to us.

"Why, don't you know?" the bright little girl promptly replies. "They have come to form a Naming Council, to give my little baby sister an Indian name. You see," she added, "Sagastao and I were born among the Cree Indians, but baby was born here among the Saulteaux. Just think: the first little white baby born among them! And they want to give her a nice Saulteaux name. The reason why they are talking so much now, before they form the council, is that lots of them have pet names they want to give our baby, but of course she can only have one."

"Yes," said Sagastao, "and our old Mary is trying to get the women to oppose the name that Souwanas will offer, just because she is down on him. But I'll bet he will beat her yet."

"You should not say, 'I'll bet.' Mother has often told you that it was very rude," reprovingly said little Minnehaha. "You never learned it from father or mother. You must have picked that up from some rough trader."

"Well, all right, I'll not say it again, but I'll bet—no, I mean—hurrah! for Souwanas and his side, anyway," and off he ran.

"Dear me!" said the little sister. "I do have so much trouble with that boy!"

Soon the council assembled. The men and women arranged themselves in a big circle and spent some time in drinking some strong, well-sweetened tea that had been prepared for them. They had been desirous of having their usual pagan ceremonies, but of course this could not be allowed, so the ceremonies of tea drinking and their usual smoking were substituted. Then the little baby was brought in by her nurse and handed to one of the oldest women. She took the child, and after kissing her and uttering some words of endearment passed her on to the woman on her left. She in her turn kissed her, uttered some kindly words, and passed her on to the next. So baby went from hand to hand until she had made the complete circle of women and men. This was the ceremony of adopting the child into the tribe.

Mary, the nurse of the older children, was excluded from this circle as she was of another tribe. After some more tea had been drunk the child was again sent on her rounds. This time each person, as he or she held the child, pronounced some Indian name that he or she wished the babe to be called. Mary, who had now crowded herself into the circle, persisted in having a voice in the matter. She wanted the child to be called Papewpenases (Laughing Bird), but she was voted down by the crowd, who said:

"No, that is Cree; we must have Saulteaux."

With a certain amount of decorum each name suggested was discussed, only to be rejected.

For a time there was quite a deadlock, as no name could be decided upon.

"Now that you have all spoken," said Souwanas, "and cannot come to any agreement, I, as chief, will make the final decision. This is the first white child born among us, as Sagastao and Minnehaha, whom we all love, were born at Norway House, among the Crees. Most of the names which you have suggested have some reference to birds and their sweet songs. A compound name, which will include these ideas and mine, Souwanas (South Wind), can surely be found."

This suggestion was well received, as Florence was born in the spring of the year, when the birds, returning from the South, filled the air with melody after the long stillness of that almost Arctic winter.

So busy brains and wagging tongues were at work, and the result was the formation of the following expressive name, which was quickly bestowed upon the child. It was first loudly announced by Souwanas himself: Souwanaquenapeke; which in English is, "The Voice of the South Wind Birds."

At once all the Indians took it up and uttered it over and over again, so that it would not be forgotten. Even Sagastao and Minnehaha, who could talk as well in the Indian language as in English, took up the word and shouted out, Souwanaquenapeke, until they had it as thoroughly as their own.

Mary alone was vexed, and so annoyed that she could not conceal her disappointment. This was particularly noticed by Sagastao, and as soon as Minnehaha joined them they slipped quietly away together. Having obtained permission they took a canoe and went for a paddle on the quiet lake. Mary, like all other Indians, was passionately fond of the water, and in spite of her crooked back was a strong and skillful paddler.

The children were placed in the center of the canoe, on a fur rug, while Mary seated herself in the stern and paddled them over the beautiful sunlit waves.

For a time but little was heard, for the children were absorbed in the scenes of rarest beauty or watched some fish, principally the active gold eyes, sporting in the water around them.

After a while the children began to clamor for a story, but Mary would not speak a word. Sagastao suspected the cause of Mary's unusual silence.

"What is the use, sakehou," he protested, "of your being in a pet because baby was not named Papewpenases? The name they gave her pleased everybody else; you must be pleased too."

"If you are cross and won't speak to us we will go and run away to Souwanas; won't we?" said Minnehaha.

This was too much for Mary, and she quickly surrendered and made an excuse about thinking of some beautiful story to tell them when they should land on that little rocky island just ahead of them.

"Very well," said Sagastao, "let us have the one about how medicines were discovered and given to the Indians to cure diseases."

"Just the one I was thinking about," said Mary; "and while we rest on the lovely white sand I will tell you the story."

A few vigorous strokes of the paddle sent the canoe well up on the sandy shore, and soon they all landed. A good romp relieved them of the stiffness caused by the cramped position in the canoe. Then as they cuddled down in the warm sand Mary began her story.

"You remember, little sweethearts, how the animals of various kinds held councils and decided to be revenged on the human family for their cruelty by sending diseases among them. Well, these creatures did as they said they would and the result was that lots of men died, and also the women and children, that did the creatures no harm, were getting different kinds of sicknesses and many of them were dying.

"Were there no diseases among them before these times?" inquired Minnehaha.

"No; not what you might call diseases," replied Mary. "The people lived such simple lives that, with the exception of accident, such as being drowned in great storms or killed by falling trees, or something that way, nearly all the people died of old age."

"Then they had no doctors in those days?" asked Sagastao.

"No; there were no medicine men in those times. Although there were those skillful to set broken limbs or attend to any who happened to be accidentally wounded, but that was nearly all. Then all at once these diseases sent by the angry animals began to appear among them, and, of course, there was much alarm. The people did not know what had brought them, nor how to get rid of them. Many people were sick and numbers of them died.

"You see, the animals held their councils in secret, and away from the presence of men, and so it would never have been known if the ground squirrel, called by some the chipmunk, had not gone and told all about the councils to the men. He had always been friendly to the human race. He had attended a number of the councils and was the only animal that had ventured to say anything in the favor of man. By doing this he so enraged the other animals that some of them fell upon him with great fury, and would have torn him in pieces if he had not been able to escape into his hole in the ground. As it was, they so tore and wounded him with their teeth and claws that the stripes remain in his back to this day.

"Well, when he was healed enough to get around again he visited the abodes of the human race and was very sorry to find that the diseases sent by the other angry animals were causing much suffering and many deaths, so he revealed the whole thing to a number of men and told them to be on their guard. But even this was not sufficient. It was felt that, now that these diseases were spreading among them, they must have some remedies for the cure of them or they would all soon be destroyed.

"While thus wondering what they should do their little friend the ground squirrel came to their help again. He went about among the trees and plants, who were always friendly to man, and he told them of the sad calamities that had come to the human race.

"When the trees and plants heard what had been done by the animals to injure and destroy their friends they speedily held councils among themselves and resolved that they would do all they could to overcome the evil.

"First the great trees held their councils, talked over the matter, and decided what they could do in the way of furnishing remedies to cure these diseases that were doing so much injury. The pine and the spruce and the balsam trees said, 'We will give of our gums and balsams.' The slippery elm said it would give of its bark to make the soothing healing drink. The sassafras said it would give of its roots to make the healthful tea that will bring back health again. The prickly ash and the sumach and others volunteered their help, and spoke of the wonderful healing power there was in them, if rightly used.

"When the plants came to their council the numbers that wanted to help were very great. No one was able to keep a record of them and of the healing powers they professed to have. There was the mandrake, with its May apples, and the wintergreen, with its pretty red berries; the catnip and the bone-set, which are so good for colds; the lobelia, which is such a quick emetic; the spikenard, the peppermint, the snakeroot, sarsaparilla, gentian, wild ginger, raspberry, and scores of others. All cheerfully offered assistance.

"When the ground squirrel, who had for days been attending the council of the trees and plants, had made out his list of what remedies each tree and plant could furnish he was very much delighted, and then, thanking them for their offered assistance, he rapidly returned to the abodes of mankind and informed them of his great success.

"Of course they were very much pleased, and very grateful to the ground squirrel for his kindness and his interest in their happiness. This is the reason why the chipmunk, or ground squirrel, lives near the homes of men. You never see an Indian shoot them or the boys or girls try to snare them. They are always welcome among the trees and the wigwams. The Indians love them because they spoke up for man when the other animals turned against him, and because it was one of their ancestors that made the trees and plants reveal their good medicines for the cure of the sick."

"Now I know why it was, when I was out with the Indian boys, that they never would shoot an arrow at a chipmunk, even when I asked them to," said Sagastao.

"Yes," said Mary, "all of the Indians have heard their fathers tell of the kindness of the old father chipmunk in the days when the animals knew so much and could talk, and so they warn the children against injuring these pretty little creatures."

But it was now time they were returning. The light canoe was once more pushed down into the lake, and soon they were merrily gliding along over the clear, transparent waters to their cozy home.