CHAPTER XIII.

In the Wigwam of Souwanas—How Gray Wolf Persecuted Waubenoo, and How He was Punished by Nanahboozhoo.

"We have come to-day for a nice story about Nanahboozhoo," said Minnehaha, as she and Sagastao lifted the deerskin door at the wigwam of Souwanas, and entered with all the assurance of children who knew they were welcome.

"Did he ever do anything to punish bad fellows who were cruel to their wives and children?" asked Sagastao. "Because, if he did, I wish he would come and thrash old Wakoo, that bad fellow who has been thrashing his wife again because he said she did not snare enough rabbits to suit him."

Souwanas, who was one of the kind-hearted Indians, never cruel to any of his family, was much amused at the fire and indignation with which the young lad spoke. So after he had had comfortable seats arranged for the children among the robes and blankets he endeavored to satisfy their demands. "Nanahboozhoo," he said, "did such things long ago, but once, when he was giving a good thrashing to a man who had been very cruel to his wife, the wife, as soon as she was able, sprang up from the place where her husband had knocked her to, seized a paddle and attacked Nanahboozhoo with such fury that he resolved never to interfere again, if he could help it, in a quarrel between man and wife. And," added the old man, with a merry twinkle in his eye, "it is best for everybody, if possible, to keep out of such quarrels."

"Yes, but, mismis" (grandfather, Minnehaha's pet name for Souwanas), "you surely know a nice story in which Nanahboozhoo helped some one without getting into trouble himself."

"Of course I do, my grandchild," said the old man, "and I know you will be pleased with it.

"My story is about a lovely Indian maiden who was bothered by a cruel hunter. He was determined that she should marry him, although she did not like him, and Nanahboozhoo came to her rescue.

"The maiden's name was Waubenoo. She had the misfortune to lose both her father and mother when she was about eighteen years old. There were four children, all much younger than she, left in her sole care. They had no uncles or aunts, or other relatives, near, to take care of them, and so Waubenoo had to hunt and fish to get food for her little brothers and sisters. Fortunately her father had left a number of good traps and nets, and plenty of twine for snares, and so the industrious girl got on fairly well. The great lake near her wigwam was well supplied with fish, and the forests all round had in them many rabbits and partridges and other small game. When great storms arose on the big lake, and Waubenoo could not go out alone in her birch bark canoe to visit her nets, some of the Indians, who were pleased to see how kind and industrious she was, would overhaul her nets and bring in what fish were caught. Thus she toiled on, and with the assistance of these kind Indians she did very nicely. Her little brothers and sisters loved her dearly, and did what they could to help in the simpler and easier part of the work. Every decent person among the Indians was pleased with her industrious habits, and often, in their quiet way, had some cheery words of encouragement for her.

"But there was one exception, and this was a selfish Indian hunter who, seeing what a fine-looking, strong woman she had become, and so clever in her work with both nets and traps, resolved that she should be his wife, to work for him and do his bidding. This man had been married before and, if the reports were true which had been told, it was likely that his wife had died because of his cruelties to her. So he resolved, in his selfishness, to take Waubenoo from caring for her brothers and sisters to be his wife, and to hunt and fish for him, that he might live a life of idleness.

"Her parents being dead this selfish young Indian did not have to go to her father to buy her to be his wife. All he thought he had to do was to go and tell her she had to be his wife and come and do as he commanded her. So harsh and cold were his words, and so very rough and forbidding his looks, that, while Waubenoo was frightened, she was grave and high spirited enough to indignantly refuse his request, and to order him never to trouble her again.

"This, of course, made him very angry. He refused to go, and continued to insist on her going with him.

"Fearing that he might revenge himself upon her by doing her or the children some harm, she told him that it was her duty to stay with the little ones whom the death of the parents had left in her care; that they might perish if she now left them.

"But nothing would turn away his anger, and if it had not happened just then that some friendly Indians came along he would have cruelly beaten her. Before them he durst not strike her, and so, muttering some threats, he sulkily strode away into the forest.

"Poor Waubenoo was now sadly troubled. Lighthearted and free, she had cheerfully worked and toiled for her loved ones, but now here comes this cruel, fierce-looking man, whom she could only look on with fear and dread, and threatens to drag her away from them all. Gray Wolf, for that was his name, had a bad reputation among the Indians. The young men shunned him and the maidens took good care to be out of the way when he was around. That he would persist in his attempts to get Waubenoo all were convinced, but that he should succeed no one desired. Still, while Indian ideas on some of these things are so peculiar that no one seemed disposed to interfere, at the same time some of them were generally on the lookout for her protection. As for brave Waubenoo, while certain that he would still trouble her, she was resolved never to submit to him.

"Thus the weeks rolled on, with Gray Wolf looking for some opportunity to carry her off, and making several attempts to do so, which Waubenoo, ever alert and watchful, succeeded in preventing.

"At length his persistent attempts became so annoying that she was obliged to neglect much of her work in order to keep on her guard. Food was getting scarce because she dared not now go far from her wigwam to hunt for the partridges and rabbits and other small creatures she was so clever in snaring.

"At length she resolved to go to Nanahboozhoo and seek his aid in getting rid of this troublesome fellow. When Nanahboozhoo heard her sad story he became very angry. He was indignant that such a commendable maiden, one who had been so kind to her little brothers and sisters, should be bothered by a big, selfish, lazy fellow who only wanted her because she was so industrious and so clever at her work.

"Nanahboozhoo had heard much about her kindly treatment of the children, and of her skill in providing for their wants, so he lost no time in going back with her to her wigwam. At first the younger children were much afraid of him, as they, like all other Indian children, had heard such wonderful tales about him. But he was in such a jolly good humor that day, and was so delighted with everything he saw about Waubenoo's wigwam and with the proofs of her industry that he soon made friends with all the children. How to go to work to give Gray Wolf such a lesson that he would never trouble them any more he hardly knew at first. However, he had not been there many hours before he had to come to a decision, for one of the little children came rushing into the wigwam with the terrible news that Gray Wolf, carrying a big dog whip and looking very angry, was coming along the trail. Nanahboozhoo only laughed when he heard this, and he very quickly decided what to do. 'Sit down there,' he said to Waubenoo, 'in that dark side of the wigwam, with a blanket over your head, and keep perfectly still until I call you; and you, children, must keep quiet. Do not be frightened or say a word, no matter what happens.'

"Then Nanahboozhoo, who, as you know, could change himself into any form he liked, suddenly transformed himself so as to look exactly like Waubenoo. So perfect was his resemblance to her, even to his dress, that her brothers and sisters could not have detected the disguise. Indeed, the young ones could not help looking over to the spot where the real Waubenoo sat in the gloom with the blanket drawn over her head. But they were Indian children, early trained to be quiet and do as they were told, and so they fully obeyed his commands.

"Of course, when Gray Wolf came into the wigwam he was completely deceived, and now, thinking that he had caught Waubenoo when there were no friendly Indians around, he at once began speaking very fiercely to her:

"'I have asked you for the last time,' he said, 'and now I have come with my dog whip and I intend giving you a good thrashing and then driving you to my wigwam. I intend to call you Atim, my dog, and like a dog I am going to thrash you.'

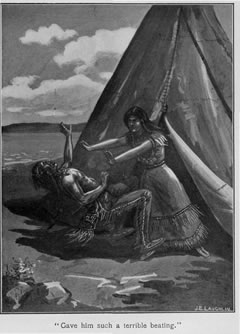

"He then savagely raised the whip to strike, as he thought Waubenoo, but the blow never reached its victim, or even Nanahboozhoo in his disguise, at whom it was aimed, for Nanahboozhoo was so enraged that anybody in the shape of a man could be so cruel and selfish as to come and threaten a kind young woman like Waubenoo that he suddenly sprang at Gray Wolf, and seizing him by his scalp lock he dragged him out of the wigwam, and then wrenching the heavy whip out of his hand gave him such a terrible beating that he remembered it as long as he lived. Then roughly throwing him to the ground, Nanahboozhoo, still in the disguise of Waubenoo, hurried into the wigwam and said to the real Waubenoo:

"'Now, while he is weak and cowed, go out and talk sternly to him, and tell him that if he ever troubles you again it will be worse for him than this has been.'

"When Waubenoo came out her appearance so terrified Gray Wolf that he tried to get up and skulk away, weak as he was. Waubenoo, glad that her enemy was so conquered that he would not be likely to trouble her much more, did as Nanahboozhoo requested her.

"Nanahboozhoo was heartily thanked by Waubenoo and the children for thus ridding them of this bad Indian, who had for so long made their lives miserable. Ere he left Nanahboozhoo warned the children to say nothing about his coming, 'for,' said he, 'if Gray Wolf finds out who it was that thrashed him he may yet be troublesome.'

"Well would it have been for all if the children had remembered this advice," added Souwanas.

"O tell us what they did, and what happened," shouted Sagastao.

"Not to-day," said the old man; "it is time you both were back at your lessons, and as I am going that way with some whitefish I will take you with me in my canoe."

"But is that all about the story of Waubenoo and the children?" said Minnehaha.

"Yes," said Souwanas, "until we come to the next. For a long time after Gray Wolf received the beating he kept away from them, although his heart was full of anger and revenge. Although he was a big fellow he feared to again threaten her who, although she seemed but an ordinary-sized Indian maiden, possessed the strength that had enabled her to give him such a thrashing."