CHAPTER II.

The Children's Return—Indignation of Mary, the Indian Nurse—Her Pathetic History—Her Love for the Children—The Story of Wakonda, and of the Origin of Mosquitoes.

In reaching home the children were quietly received by their parents, who, understanding Indian ways, had no desire to lessen their influence by finding fault with them for carrying off the children. They treated the matter as though it were one of everyday occurrence.

Mary, the Indian nurse, however, did not regard the incident so calmly. When the children were brought back dirty, greasy, bedaubed, and so tired that they could hardly hold up their little heads, her indignation knew no bounds, and as she was perfectly fearless she couched her sentiments in the most vigorous phrases of the expressive Cree language.

The history of Indian Mary was very strange. Indeed there was an incident in her life so sad that from the day of her recovery she was considered to be under the special care of the Good Spirit, so that even the most influential chiefs or hunters had a superstitious fear of showing any temper, or making any bitter retort, no matter what she might say.

Years before this time Mary was the wife of a cruel pagan Indian who bore the English name of Robinson. Although she was slight of figure, and never very strong, he exacted from Mary a great deal of hard work and was vexed and angry if, when heavily burdened with the game he had shot, she did not move as rapidly along on the trail as he did, carrying only his gun and ammunition.

Once, when they were out in the woods some miles from his wigwam, he shot a full-grown deer and ordered her to bring it into the camp on her back. Picking up his gun he started on ahead, and being a large, stalwart man, and moving with the usual rapidity of the Indians on the homeward trail, he soon reached his wigwam. Unfortunately for him—and, as it turned out, for Mary also—he found some free-traders [ Fur buyers who were not agents of the Fur Company.] at his abode awaiting his return. They had few goods for trade in their outfit, but they had a keg of fire water, which has ever been the scourge of the Indians.

Robinson informed them of his success in shooting the deer and that it was even now being brought in. The traders not only purchased what furs Robinson had on hand but also the two hind quarters of the deer which Mary was bringing home. Robinson at once began drinking the fire water which he had received as part payment.

He was naturally irritable, and short-tempered even when sober, but he was much more so when under the influence of spirituous liquors. The unprincipled traders, knowing this, and wishing to see him in one of his tantrums, began in a bantering way to question whether he had really shot a deer, since his wife was so long in coming with it.

This made him simply furious, and when Mary did at length arrive, laboring under the two-hundred-pound deer, she was met by her husband now wild with passion and the white man's fire water. Little suspecting danger she threw the deer from her shoulders, where it had been supported by the carrying strap across her forehead. Weary and panting, she turned to go into the wigwam for her skinning knife, but ere she had gone a dozen steps she was startled by a yell from Robinson which caused her instantly to turn and face him. The sight that met her eyes was appalling. Before her stood her husband with an uplifted gleaming ax in his hands and curses on his tongue. Seeing that there was no chance to fly from him she threw herself toward him, hoping thereby to escape the blow. She succeeded in saving her head, but the ax buried itself in her spine.

Mary's piercing screams speedily brought a number of Indians from neighboring wigwams. When they found poor Mary lying there in agony, with the ax still imbedded in the bones of her back, their indignation knew no bounds.

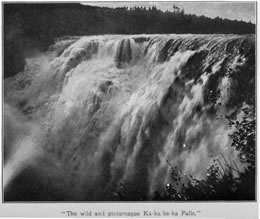

Indians, as a rule, have great self-control, but this sight so stirred them that there was very nearly a lynching. Robinson, now sobered by his fears, clearly foresaw that terrible would be his punishment, and while the Indians and traders turned to attend to Mary's wounds the wretched husband stealthily slipped away into the forest and was never again seen there. Rumors, however, at length reached Mary that he had fled away to the distant Kaministiquia River, where for a time he lived, solitary and alone, in a little bark wigwam. One day, when out shooting in his canoe, he was caught in some treacherous rapids and carried over the wild and picturesque Ka-ka-be-ka Falls, about which so many thrilling Indian legends cluster.

For seven years Mary was a helpless invalid. When she did recover her back had so curved that she looked like a hunchback. As she was poor, and utterly unable either to hunt or to fish, we helped her in various ways. She was always grateful for kindness, and in return was very willing to do what she could for us. She was exceedingly clever with her needle, and with a little instruction was soon able to assist with the sewing required. However, what especially won her to us and gave her a permanent place in our home, was her great love and devotion to our little ones.

Little Sagastao was only a few months old when she installed herself as his nurse, and for years she was a most watchful and devoted as well as self-sacrificing guardian of our children in that Northern home. She seemed to live and think solely for them. At times, especially in the matter of parental discipline, there would be collisions between Mary and the mother of the children; for the nurse, with her Indian ideas, could not accept of the position of a disciplined servant, nor could she quietly witness the punishment of children whom she thought absolutely perfect. Hence, if she could not have things exactly as she wanted them, Mary would now and then allow her fiery temper to obtain the mastery, and springing up in a rage and throwing a shawl over her head she would fly out of the house and be gone for days.

Her mistress paid no attention to these outbursts. She well knew that when Mary had cooled down she would return, and it was often amusing to see the way in which she would attract the children's attention to her, peering around tree or corner, and then come meekly walking in with them as though they had only been for a pleasant outing of an hour or so.

"Well, Mary," would be the greeting of her mistress, while Mary's quiet response would be the Indian greeting of, "Wat cheer!"

Then things would go on as usual for perhaps another six months, when Mary would indulge again in one of her tantrums, with the same happy results.

She dressed the children in picturesque Indian costumes—coats, dresses, leggings, moccasins, and other articles of apparel of deer skin, tanned as soft as kid, and beautifully embroidered with silk and bead work. Not a spot could appear upon their garments without Mary's notice, and as she always kept changes ready she was frequently disrobing and dressing them up.

When Souwanas and Jakoos came that morning and picked up the children Mary happened to be in another room. Had she been present she would doubtless have interfered in their movements. As it was, when she missed the children her indignation knew no bounds, and only the most emphatic commands of her mistress restrained her from rushing after them. All day long she had to content herself with muttering her protests while, as usual, she was busily employed with her needle. When, however, the two stalwart Indians returned in the evening with the children on their shoulders the storm broke, and Mary's murmurings, at first mere protests, became loud and furious when the happy children, so tired and dirty, were set down before her. The Indians, knowing of the sad tragedy in Mary's life, would not show anger or even annoyance under her scathing words, but, with the stoical nature of their race, they quietly endured her wrath. This they were much better prepared to do since neither of the parents of the white children seemed in the slightest degree disturbed by their long absence or the tirade of the indignant nurse. With high-bred courtesy they patiently listened to all that Mary had to say, and when the storm had spent itself they turned and noiselessly retired.

The children were worn out with their day's adventure, and their mother intimated that Mary ought at once to bathe them and put them to bed. This, however, did not satisfy Mary. It had become her custom to dress them up in the afternoons and keep them appareled in their brightest costumes during the rest of the day; therefore now the weary children, after being bathed, were again dressed in their best and brought out for inspection and a light supper before retiring. The bath and the supper had so refreshed them that when Mary had tucked them into their beds they were wide awake and asked her to tell them a story. But sleep was what they needed now more than anything else, and she tried to quiet them without any further words, but so thoroughly aroused were they that they declared that if she refused they knew somebody who would be glad to have them visit him again, and that he would tell them lots of beautiful things.

This hint that they might return to the wigwam of Souwanas was too much for Mary, who very freely gave utterance to her sentiments about him. The children gallantly came to the defense of the old Indian and also of Nanahboozhoo, of whom Mary spoke most slightingly, saying that he was a mean fellow who ought to be ashamed of many of his tricks.

"Well," replied Sagastao, "if you will tell us better stories than those Souwanas can tell us about Nanahboozhoo, all right, we will listen to them. But, mind you, we are going to hear his Nanahboozhoo stories too."

"O, indeed," said Mary, with a contemptuous toss of her head, "there are many stories better than those of his old Nanahboozhoo."

"Won't it be fun to see whose stories we like the best, Mary's or Souwanas's!" said Minnehaha, who foresaw an interesting rivalry.

Mary had now committed herself, and so, almost without realizing what it would come to, she found herself pitted against Souwanas, the great story-teller of the tribe. However, being determined that Souwanas should not rob her of the love of the children, she was tempted to begin her story-telling even though the children were exhausted, and so it was that when the lad asked a question Mary was ready.

"Say, Mary," said Sagastao, "the mosquitoes bit us badly to-day. Do you know why it is that there are such troublesome little things? Is there any story about them?"

"Yes. Wakonda, one of the strange spirits, sent them," said Mary, "because a woman was lazy and would not keep the clothes of her husband and children clean and nice."

"Tell us all about it," they both cried out.

Mary quieted them, and began the story.

"Long ago, when the people all dressed in deerskins, there was a man whose name was Pug-a-mah-kon. He was an industrious fellow, and had often to work a good deal in dirty places. The result was that, although he had several suits of clothes, he seemed never to have any clean ones.

"It was the duty of his wife to scrape and clean his garments and wash and resmoke them as often as they needed it. But she neglected her work and would go off gossiping among her neighbors. Her husband was patient with her for a time, but at length, when he heard that Wakonda was coming to pay a visit to the people, to see how they were getting along, he began to bestir himself so as to be decently attired, in clean, handsome apparel, to meet this powerful being, who was able to confer great favors on him, or, if ill-disposed, to injure him greatly.

"He endeavored to get his wife to go to work and remove the dirt that had gathered on his garments. She was so lazy that it was only from fear of a beating that she ever did make any attempt to do as he desired. She took the garments and began to clean them, but she was in a bad humor and did her work in such a slovenly and half-hearted way that there was but very little change for the better after the pretended cleaning.

"When the news was circulated that Wakonda was coming, the husband prepared to dress himself in his best apparel, but great indeed was his anger and disgust when he found that the garments which he had hoped to wear were still disgracefully grimy.

"While the angry husband was chiding the woman for her indolence Wakonda suddenly appeared. To him the man appealed, and asked for his advice in the matter.

"Wakonda quickly responded, and said: 'A lazy, gossiping wife is not only a disgrace to her husband, she is annoying to all around her; and so it will be in this case.'

"Then Wakonda told her husband to take some of the dirt which still clung to his garments, which she was supposed to have cleansed, and to throw it at her. This the man did, and the particles of dirt at once changed into mosquitoes. And so, ever since, especially in the warm days and nights of early summer when the mosquitoes with their singing and stinging come around to trouble us, we are reminded of this lazy, slovenly woman, who was not only a trial to her husband, but by her lack of industry and care brought such a scourge upon all the people."

"Didn't Wakonda do anything else?" murmured the little lad; but that blessed thing called sleep now enfolded both the little ones, and with mutterings of "Nanahboozhoo—Wakonda—Souwanas—Mary"—they were soon far away in childhood's happy dreamland.